- October 11, 2023

- by Kavita Tailor, Associate Manager, Ei Mindspark

- Blog

- 0 Comments

Detecting pathways to scale: Discovering the key catalysts and barriers to teacher EdTech Adoption in India

Author : Kavita Tailor, Associate Manager Ei

Over the past decade, numerous EdTech interventions have been introduced and trialled in India’s government schools to improve student learning. Though there is a growing body of evidence to demonstrate the positive impacts of EdTech tools on student learning outcomes, the extent to which they have been adopted by teachers is less explored. As teachers are key stakeholders within EdTech implementation processes, proposed EdTech solutions must be relevant, accessible and aligned with teacher pedagogy. This can increase teachers’ acceptance of EdTech and the likelihood that it is integrated into their regular teaching practices.

Ei Mindspark, a personalised adaptive learning (PAL) tool, has operated in India’s public schools since 2010. The tool has reached over 600 schools leading to improved learning outcomes for more than 400k+ students. However, expanding Mindspark in India’s public schools without external support has remained a pertinent challenge. Gaining teacher buy-in has been critical to strengthening Mindspark’s integration into public schools and achieving scale. To understand how Mindspark’s implementation processes can be adapted to better equip and motivate teachers, we carried out interviews with government school teachers in Punjab. This blog summarises the main learnings from the teacher interviews conducted.

Sample and methodology

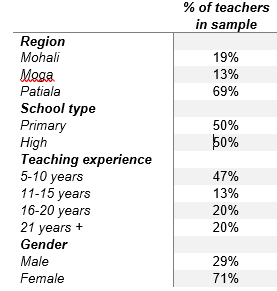

In-depth interviews were conducted with 18 government school teachers in Punjab. The sample equally represented teachers from primary and high schools where all teachers had five or more years of teaching experience. Further details on the teachers interviewed can be found in Table 1.

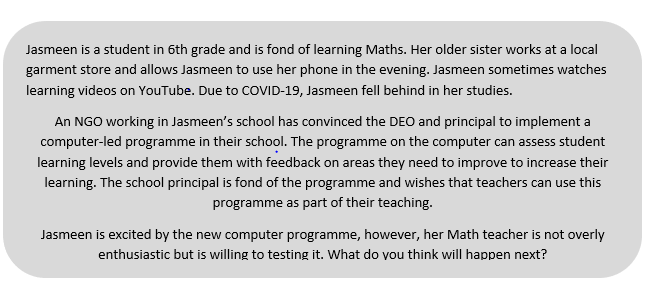

Vignette research methodology was used in this study to explore the key behavioural barriers and enablers for teachers in adopting PAL tools. Two key instruments depicting different scenarios were established to elicit the opinions and attitudes of teachers on the integration of EdTech in classrooms. An exemplary vignette is shown in Figure 1.

Key findings

Teachers undertake a highly versatile role

It is well documented that public school teachers in India are often responsible for many government-driven administrative tasks in addition to their teaching responsibilities (e.g. managing examination enrolment and funds, scholarships, election duties, midday meals, census etc.). For some teachers, this creates a burden on their workload and can undermine their self-perception as teachers, with a growing self-regard as clerical workers. This consideration can lead to resistance when acquiring additional responsibilities not directly related to teaching, and those where the value of student learning is not immediately recognised. PAL tools are often mistakenly linked to administrative tasks as teachers are not at the forefront of teaching and learning occurs independently and gradually. However, some teachers take pride in the fact they are productively navigating a multi-faceted role, increasing their confidence in tackling any task at hand. This positive attitude can be promising when introducing and gaining buy-in for new EdTech initiatives.

Teachers can be motivated by various intrinsic and extrinsic factors

Some teachers are intrinsically motivated by their want to be a successful educator, a key role model in their students’ lives and a figure for which their students can seek support for academic and non-academic concerns.

“I feel that even if 2-3 kids can move out of their shackles then that is enough for me” – Primary School Teacher, Patiala

However, few teachers appeared to rely on their internal motivations for teaching while many highlighted the lack of extrinsic sources of motivation to uptake any additional responsibilities. For example, many brought up the lack of implications for teachers when succeeding in their role and doing below the minimum.

“Here there is no reward for anyone who works more. There is no punishment for someone who doesn’t do any work also. Until this changes, there is no change which is going to come.” – Primary School Teacher, Patiala

The act of recognition emerged as a key motivational factor from teacher interviews. Generally, teachers value recognition from heads or members of the state education department beyond that of school principals. Whether recognition is conveyed through certification, awards, verbal appreciation or simply the retention of teachers’ names, these actions hold stronger importance when publicised by those positioned further up the educational hierarchy.

While positive recognition from District Education Officers (DEOs) or Principal Secretaries is a key motivator for teachers, orders administered by these individuals also seemed to trigger teacher motivation. For instance, when asked about the likelihood of success for PAL integration in schools, a common response suggested that if the programme is mandated and monitored by education officials, it is most likely to be effective.

Although teacher motivation can be triggered via recognition by education officials, orders administered by DEOs or secretaries are somewhat limited in their influential power. As these directives primarily affect teachers’ extrinsic motivation rather than intrinsic, teachers are less likely to independently sustain new practices. Additionally, the prevailing influence of higher-ranking individuals in the educational hierarchy can diminish the role of lower-ranking individuals by limiting their ability to initiate action. For instance, when orders are not administered by top-level authorities, they are perceived as less critical, leaving principals and teachers with a sense of powerlessness and the freedom to be less proactive.

“In my perspective, if the instructions and order come officially that is the best. In India, this is how things are done. Outside India, nobody has to force anyone to do anything. Here we need orders and rules. If there is no one who monitors or pushes, everyone is hesitant to take-up responsibility.” – Middle School Teacher, Mohali

While the strict administration of education guidelines has proven effective, it can also have implications on how teachers perceive their role. Many teachers held the impression that educators as a collective primarily adhere to stringent government guidelines rather than being leaders of their own pedagogy. One teacher stated that “freedom and time should be given to teachers,” while another expressed that “teachers should be innovators, adopt new methods and technologies to improve learning.” This highlights the present demand to have more time dedicated to teaching and experimentation.

Teacher experiences of technology in classrooms

Many teachers viewed technology positively because of the benefits it had brought to regular classroom practices. The introduction of projectors surfaced as a recurring example, as they increased the efficiency of teachers’ work and reduced the manual preparation of teaching materials. Teachers also recognised the pedagogical benefits of projectors as they offer multimedia content that aids student retention and comprehension of certain concepts. As projectors have delivered a noticeable and direct impact on teachers’ workload, this intervention has been positively embraced and sustained within classroom practice.

“See, technology is very important, but it is important in the context of needs. Like for instance, the projector is useful – why? Because it helps in the work of the teacher.” – Primary School Teacher, Patiala

Though there is evidence to suggest that PAL solutions can generate greater student learning gains than smart classrooms, teachers often perceive the impacts of PAL to be lower as, unlike physical hardware, its impacts are not immediately recognisable.

Teacher experiences of prior EdTech programmes also generated certain views and expectations of newly introduced interventions. Teachers involved in NGO-led interventions often faced confusion regarding their specific teaching responsibilities as a result of the integration of EdTech. Here, the poorly-planned execution of the EdTech programme was the key liability. Despite teacher hesitancies towards external programmes, teachers are more likely to be receptive if they identify a common value between their pedagogy and the intervention.

Teacher perceptions of Ei Mindspark

Feedback highlighted that teachers strongly valued Mindspark’s accurate identification of student learning levels since this assessment is typically challenging. However, teachers felt that a separate facilitator was necessary to run Mindspark labs. Besides time constraints, their perception that lab facilitators must have extensive computer knowledge and experience significantly contributed to this opinion. This perception was also likely influenced by teacher experiences with technology as many expressed their limited digital skills. It was also not fully understood that teachers’ presence in labs was important not solely for technical teaching but also for academic support. The lack of understanding of an education tool’s inherent pedagogy and consequential value can often lead to the duplication of teaching and learning efforts.

Recommendations

Interviews with public school teachers have shown that many are prepared to experiment with new teaching methods to improve student learning outcomes. However, the existing educational systems and teacher perceptions around PAL can often hinder their willingness to adopt PAL tools. Below, we present some recommendations for gaining teacher buy-in for EdTech interventions as an initial step towards tackling the challenge of EdTech adoption.

- Teacher recognition: Implementing a recognition initiative for teachers within a district tied to their engagement with the EdTech programme, can motivate sustained usage and can promote healthy competition amongst schools. These can take form of non-pecuniary rewards such as appreciation letters from the District Education Officer or student testimonials.

- Government collaboration: Forming strong relationships with district-level education officers can prove advantageous in aligning EdTech initiatives with the broader district policies and objectives. Such district-level support can foster a culture of teacher commitment towards the EdTech programme.

- Planning tools: Introducing online and offline planning tools that can streamline the organisation of EdTech-related tasks can reduce administrative responsibilities for teachers, potentially boosting their enthusiasm. For example, a mobile application that shares computer lab schedules alongside user-friendly daily task suggestions for teachers can prove useful.

- Leveraging technology pioneers: Recognising educators who are at the forefront of technology adoption and collaborating with them to disseminate their experiences and achievements with the EdTech program can generate a broader influence within teacher circles. This form of peer-driven communication can signify transformation and resonate more effectively with teachers, as it originates from their peers.

While these approaches are practical, EdTech implementors must strike the right balance between imposing EdTech upon teachers and ensuring the tool is proving beneficial and enjoyable for teachers.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Saksham Singh from The University of Wisconsin-Madison and Aditya Laumas for their expertise and efforts in conducting comprehensive in-depth interviews with Mindspark stakeholders and ensuring the collection of high-quality data.