- December 9, 2023

- by Educational Initiatives

- Blog

- 0 Comments

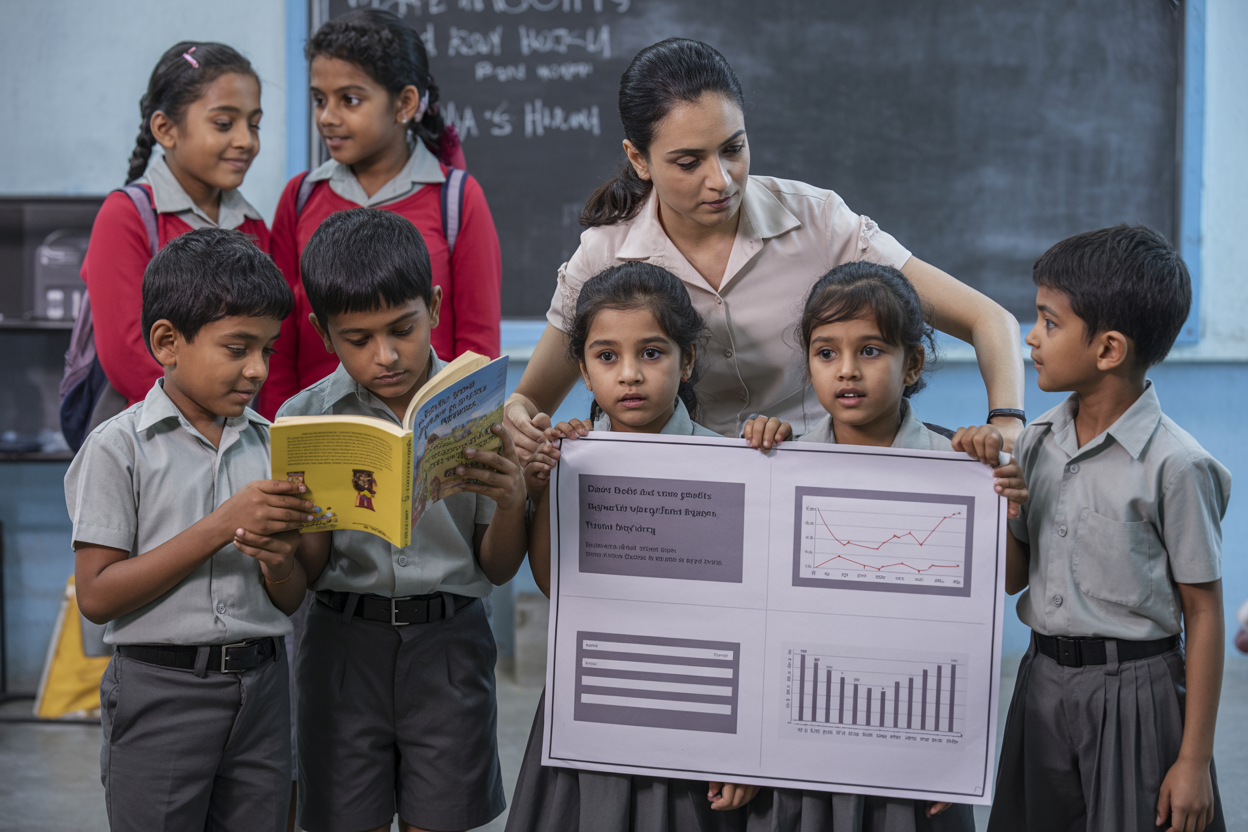

In a teacher training workshop on Language Assessments, it was asked why a certain poster-type text, containing graphs, can be used as a text to assess reading comprehension. This participant stuck to their opinion that such a text is essentially “Mathematics”, and we should stick to “Language” when assessing/teaching reading comprehension. This is an important question, and we should explore the role played by the type of text in reading comprehension, and what makes a text “appropriate” in teaching/assessing reading comprehension.

Now, we know that reading comprehension is important, nay, crucial, to language learning. The purpose of language learning is achieved when the child is able to comprehend and engage with all the information present around us. The basis of education is laid by the ability to comprehend different types of texts, across subjects. Reading Comprehension requires reading quickly (reading fluency), remembering recently read information – keeping track of all the words in a sentence (working memory), meaning-making and prosodic behaviour (semantics/grammar), and understanding what is read (receptive language). [1]

Reading comprehension is a complex process. Dr. Hollis Scarborough speaks of skilled reading as resembling the “strands” of a rope. The Reading Rope consists of lower and upper strands. The word-recognition strands (phonological awareness, decoding, and sight recognition of familiar words) work together as the reader becomes accurate, fluent, and increasingly automatic with repetition and practice. The language-comprehension strands (background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge) reinforce one another and then weave together with the word-recognition strands to produce a skilled reader.[2]

Scarborough’s Reading Rope: A Groundbreaking Infographic;

Scarborough’s Reading Rope: A Groundbreaking Infographic;

The Examiner Volume 7, Issue 2 April 2018, International Dyslexia Association (IDA)

The reader’s ability to comprehend a text depends on a variety of factors; broadly these can be categorised as follows:

Different types of texts will influence these factors differently. Remember our school days when a story, a descriptive text, and/or a poem would come as “unseen passages” in the exam paper? But higher comprehension ability with these limited types of texts may not indicate an overall higher reading comprehension ability. The reason for our textbooks having stories, narratives, descriptions, dialogues, poems, etc. is to help us learn meaning-making better. Comprehension is not a linear neurocognitive activity, but involves multiple processes happening simultaneously, as can also been seen from the Scarborough’s Rope mentioned earlier. The overall comprehension ability increases as our ability to make meaning out of different texts increases. Comprehension of just 1-2 types of texts is not enough because reading comprehension is the basis of learning in any and every subject in a written form. Keeping this in mind, we, at Educational Initiatives, have kept different types of texts across our various learning and assessment programmes to teach/assess Reading Comprehension.

Broadly, there are two main text formats: Continuous text and non-continuous text.[3]

Continuous texts are formed by sentences organised into paragraphs, e.g. newspaper reports, essays, novels, short stories, reviews, reports, blogs and letters. Non-continuous texts are most frequently organised in a matrix format, composed of a number of lists, e.g. lists, tables, graphs, diagrams, advertisements, schedules, catalogues, indexes and forms.

Non-continuous text has independent units of words or sentences, through which the reader has to retrieve information by applying different cognitive strategies. While here the text length to be read at once may be less, due to the format, the reader starts processing the reading afresh and that becomes time-intensive. In case of a continuous/connected text, however, there is a flow, an anticipation of the events, and that allows quicker reading ability and comprehension. In case of connected texts, the reader continues to access the working memory more efficiently and retrieves the information easily.

Within connected text, too, there can be different types: narrative, descriptive, expository, instructional, etc. The format and type of text will influence how the reader approaches it, and how information is retained. In narrative texts, readers are able to make connections (causal/logical and referential cohesion) within the narratives and with their own lives, thus increasing the level of engagement often coming from the identification of self or familiarity with the characters.[4] These connections can be causal/logical or correlated with overt semantic relations, such as the use of personal pronouns, demonstratives or comparatives in the text. The latter is called referential cohesion.

From our two decades of assessment data in language learning, we have consistently found that students score lower in reading comprehension questions on disconnected texts than on connected texts. The skill ‘Understands written information presented in various forms as Text, Tables, Notices, Tickets, Posters, Labels, etc.’ has consistently been one of the weakest skills.[5] This could be because children are exposed to more continuous texts in the textbooks and classrooms than certain types of non-continuous texts. Another possible reason could be that the text structures of connected texts are more easily remembered, as discussed above.

With the increasing importance of digital media, the variety of texts that we are exposed to, is constantly expanding. It becomes essential to equip our future readers with the skill to comprehend all this information around them. We can do this by including different text types in our reading comprehension instruction and assessments. Providing a variety of text formats, types and genres may support students in the use of multiple comprehension strategies, thus creating holistic readers.[6] It is important to note that we are not teaching children content, but comprehension strategies, and therefore a holistic view is what we need. Therefore, to answer the question posed by the aforementioned workshop participant – yes, graph and charts and tables (though “taught” in Mathematics) would (and should) form a part of reading comprehension instruction and assessment.

Existing research on text types and their role in developing the comprehension skill has only scratched the surface. While we can agree that exposure to all kinds of texts and their comprehension is important for students, it remains to be seen exactly how and which comprehension strategies can be taught by which texts. Hence, conducting further studies is imperative, especially in the Indian context.

1 Berninger & Richards, 2002; Cutting, Materek, Cole, Levine, & Mahone, 2009

2 Scarborough’s Reading Rope: A Groundbreaking Infographic; The Examiner Volume 7, Issue 2

April 2018, International Dyslexia Association (IDA)

3 PISA for Development Assessment and Analytical Framework: Reading, Mathematics and Science © OECD 2017

4Trabasso & van den Broek, 1985; van den Broek & Kremer, 2000

[5] Test for Student Learning ENDLINE ASSESSMENTS, 2019-2020 KEF-SLDP-GURGAON A REPORT PREPARED BY EDUCATIONAL INITIATIVES

[6] Cohen, L., Krustedt, R. L., & May, M. (2009). Fluency, Text Structure, and Retelling: A Complex Relationship. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, V49.2