Edition 06 | June 2025

Feature Article

by Anumita D V, Mindspark English

What Lies Beyond Readability?

Reading is a beautiful paradox. It is simple, because it is one of the most fundamental human activities, yet also

wonderfully complex, because it is supported by a rich network of cognitive processes. This paradox makes

reading both challenging to measure and exciting to teach. This is especially true in the diverse contexts of the

Indian learning landscape, where students access vocabulary in different ways and bring unique backgrounds to

the table. It is quite evident, then, that in such an ecosystem, one cannot take a one-size-fits-all approach to

teaching reading comprehension, especially when its students are second or even third language learners.

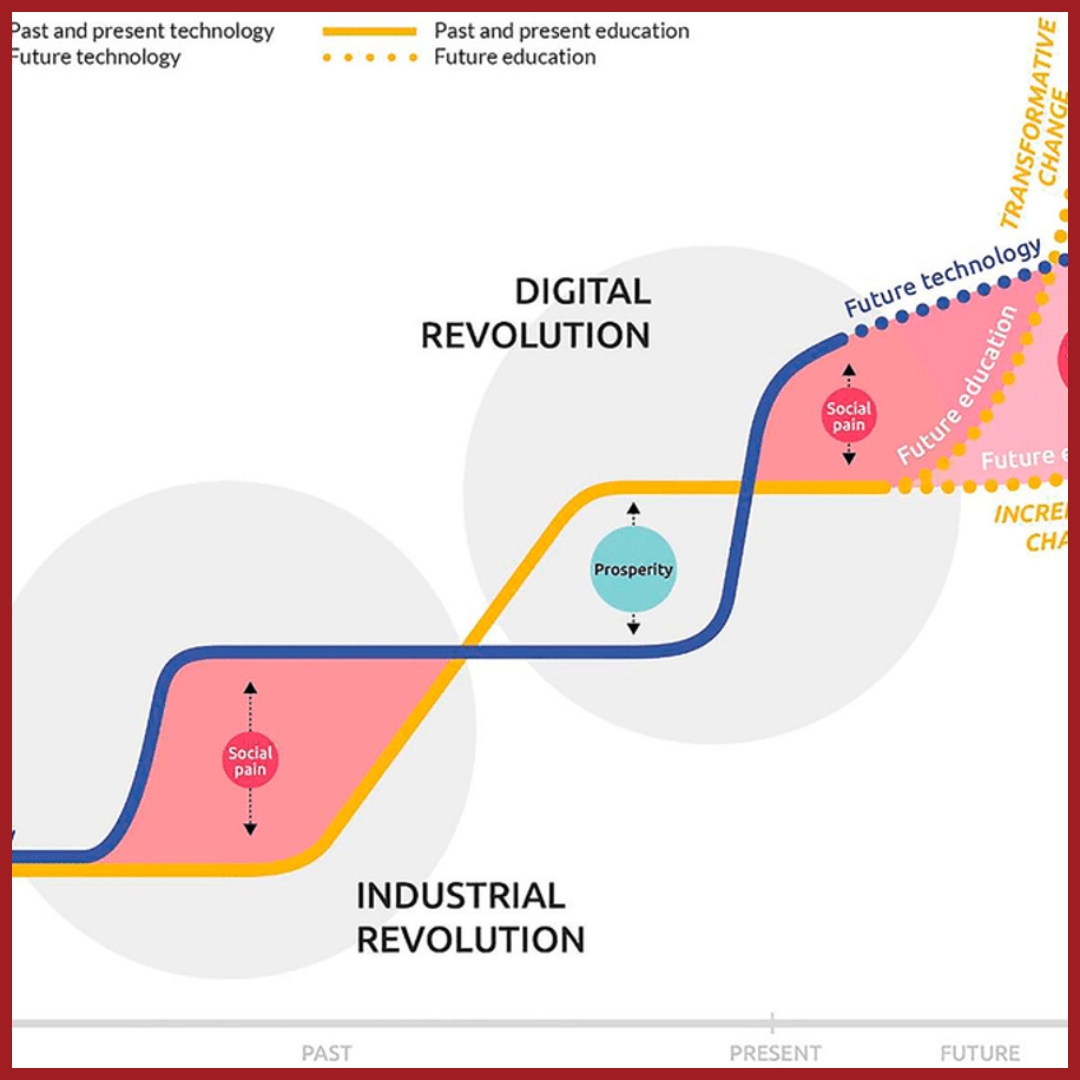

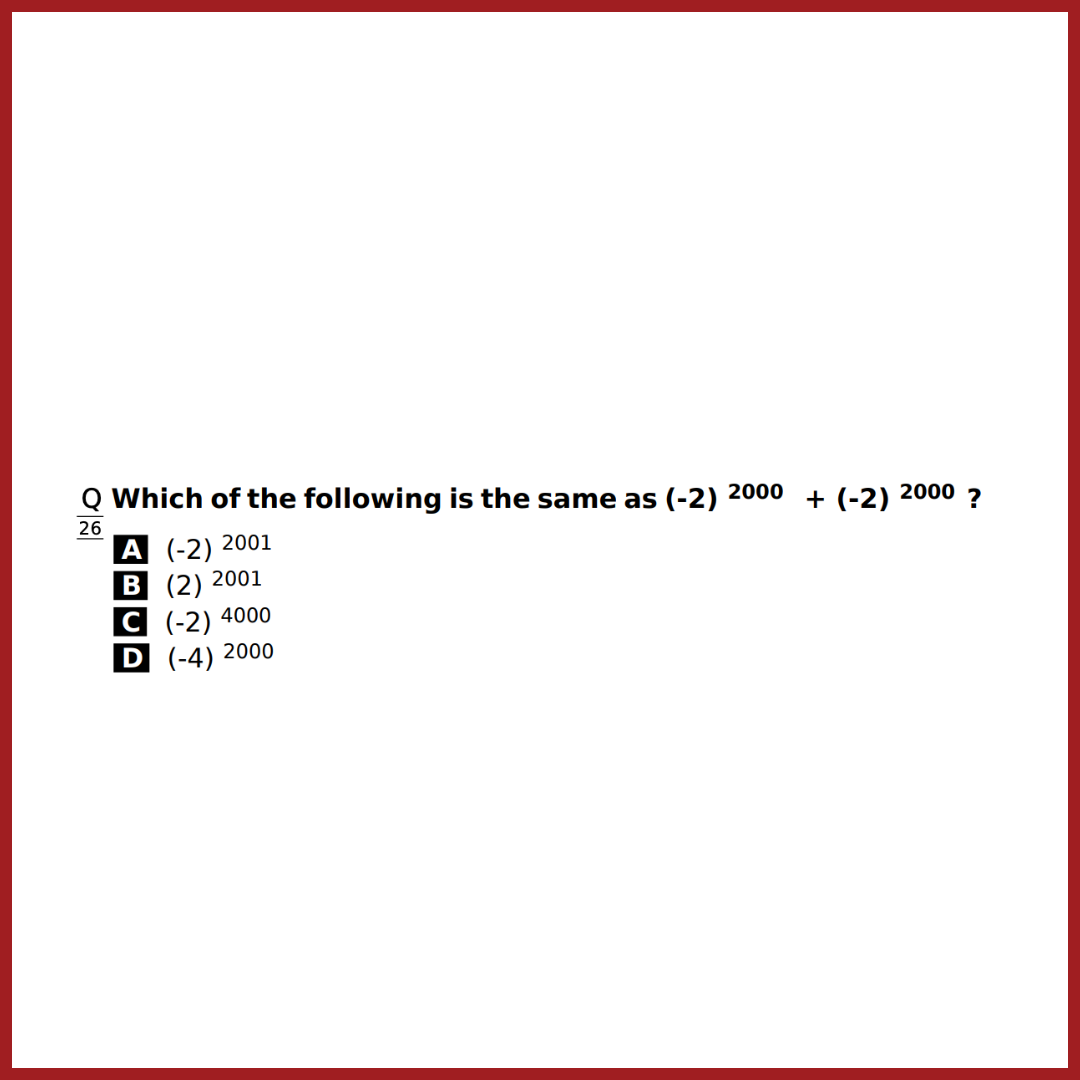

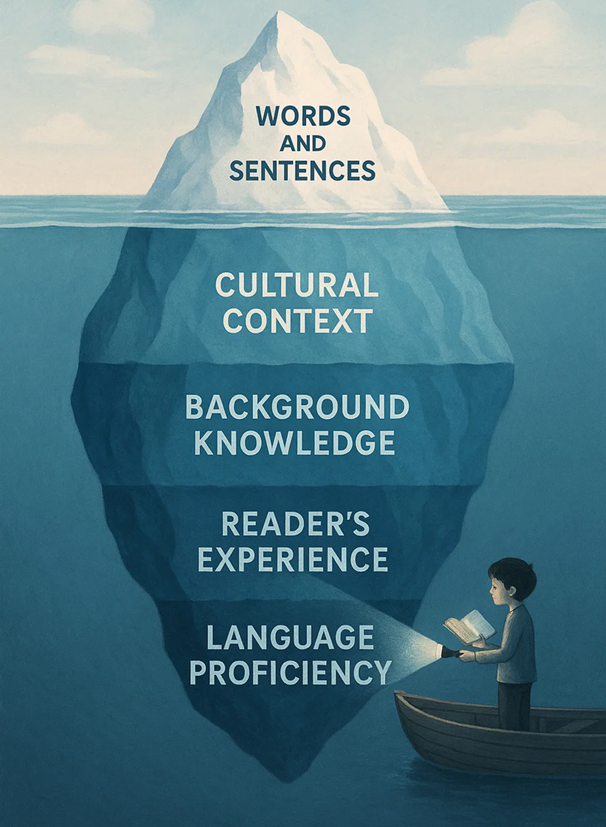

‘Universal’ metrics of reading comprehension typically centre around readability indices based on word length

and frequency, as well as semantic and syntactic difficulty. However, these are often just proxies—intermediaries

or substitutes—which translate the complex processes of reading comprehension into numbers. After all,

comprehension is not only about decoding words or grammar. A reader needs to use prior knowledge, cultural

context, and engage with the text to truly comprehend what it is saying. Two passages might score similarly on a

readability scale but evoke entirely different levels of understanding, depending on a learner’s background,

language proficiency, and exposure to the subject matter. We must remember, here, that these metrics are

modeled on cultures and language patterns that come naturally to first-language learners. Therefore, they do not

consider the challenges of learning English as a second language. For instance, what are the challenges in

navigating word meanings across languages? As educators in this context, therefore, it is our responsibility to

ask: How far do we need to go to make a passage truly accessible and meaningful for such a learner? What are

the implicit challenges in bringing the reader up to the text instead of bringing the text down to the reader?

It Isn’t as Simple as Simplification

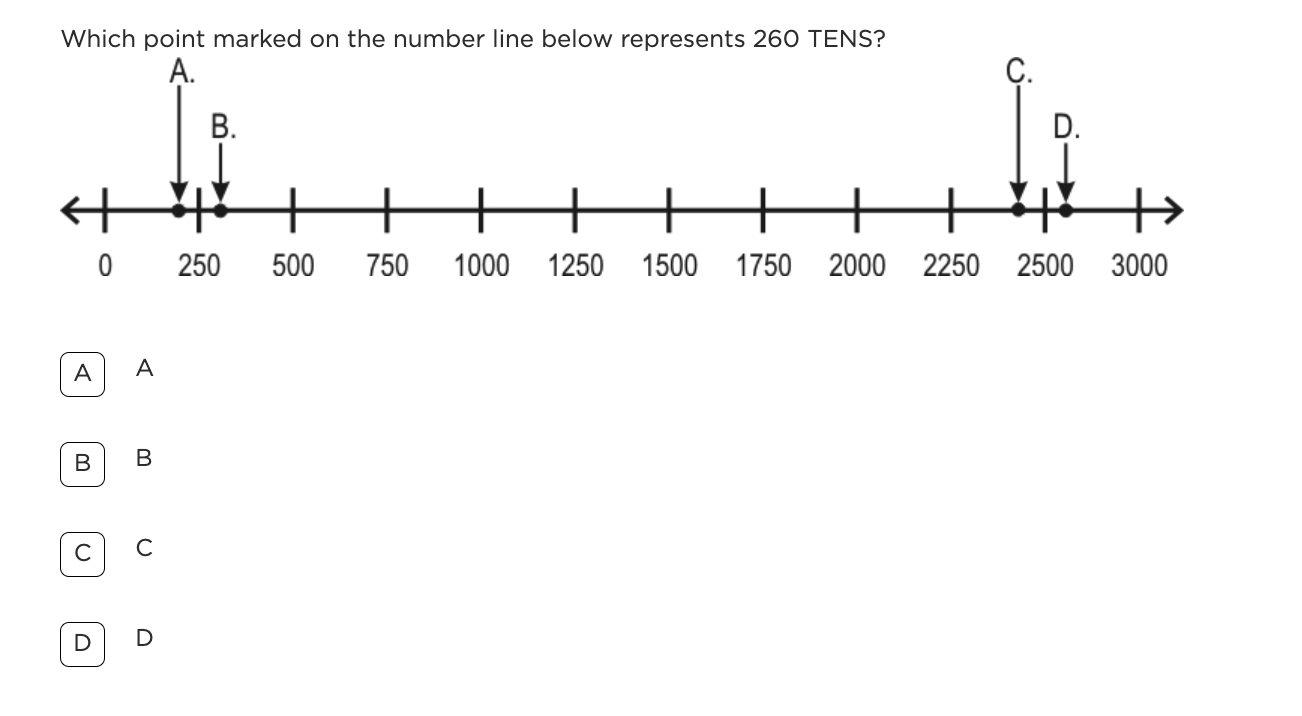

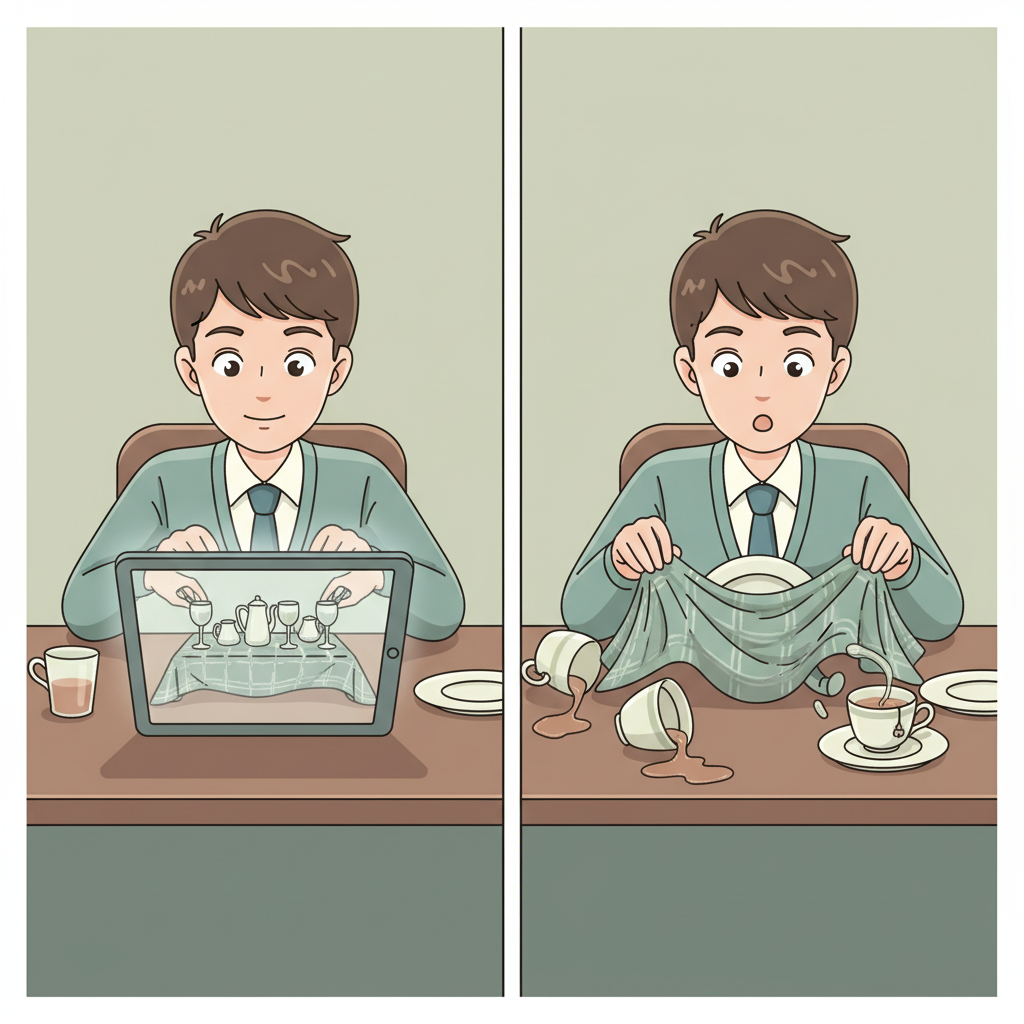

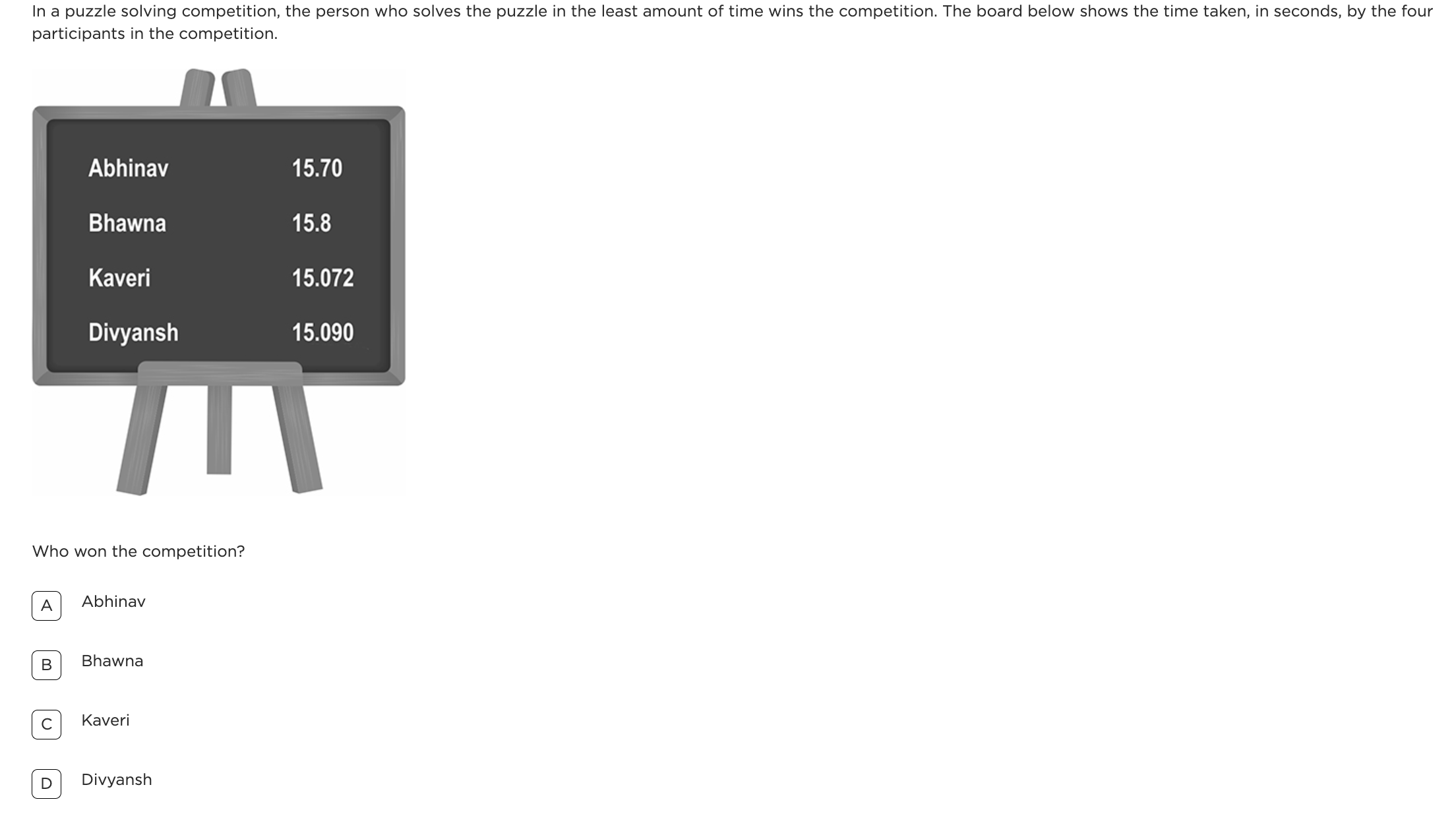

In order to answer this question, my team undertook an exercise called ‘Deconstructing Passages’. This is a

process in which we broke down texts into their smallest components, ran student pilots, and tried to map

patterns of accuracy and confusion, after which we edit passages to ensure rigour and accessibility. As a team,

we set out to discover what a good reading comprehension passage is by trying to understand what is not a

good reading comprehension passage. We’ll look at what worked and what didn’t, exploring an example where

readability indices and simplification do not expose the full nature of the passage’s difficulty.

As we set about considering the reasons for this poor performance, we began to think about hypotheses for the

potential reasons behind this poor performance. These hypotheses then guided how we edited these passages.

Our most common edits centred around adding meanings to difficult words, simplifying complex sentences, and

providing clearer context for unfamiliar terms. In some cases, we did see an increase in accuracy levels after

implementing these changes, suggesting that the passage was otherwise sound. In other cases, however, we

noted no change or a marginal decrease in accuracy levels after implementing these changes, which prompted

us to go back to the drawing board with a new problem: what were we missing in this process of reverse

engineering?

The answer, of course, was quite obvious! In the frenzy of de-constructing passages, we’d forgotten to account

for the effects of an ingredient we’d never missed when constructing a passage: cultural context. Readability

scores, while being deeply important in assessing the suitability of a passage for a given grade, are calculated

after the passage has already been created. Additionally, since they are numerical in nature, they cannot entirely

account for the experience of reading a passage, which cannot be translated into numbers. This realisation

prompted us to think about the challenges which may not be evident at first, but which deeply affect the

experience of reading a story. In this context, we can look at a passage as a machine, made up of complex,

interconnected moving parts. Each of these parts has to work together to create the story. The most important,

however, are the ‘invisible’ components, like oil and lubricants, that keep the machine running smoothly.

Let’s examine this idea with a story, (

Hey Mr.White That’s the Wrong Colour for that), which my team tagged to

Grade 6, called ‘Hey, Mr White, That’s the Wrong Colour for That’, a story about the author, Robb Smith, and his

experience living with colour blindness. He reveals his color blindness gradually; he starts with a short anecdote,

then goes on to describe various personal experiences before thinking about the larger picture of perceptions and

misunderstandings. This passage perplexed us because students repeatedly got the meaning of the term ‘colour

blindness’ wrong, despite the meaning being explicitly stated in the third paragraph of the passage. What was

interfering with their comprehension of the passage?

One of the first challenges with this passage is the time at which information is presented. The definition of

colour blindness, which is central to understanding the story, is given to us only midway through the passage.

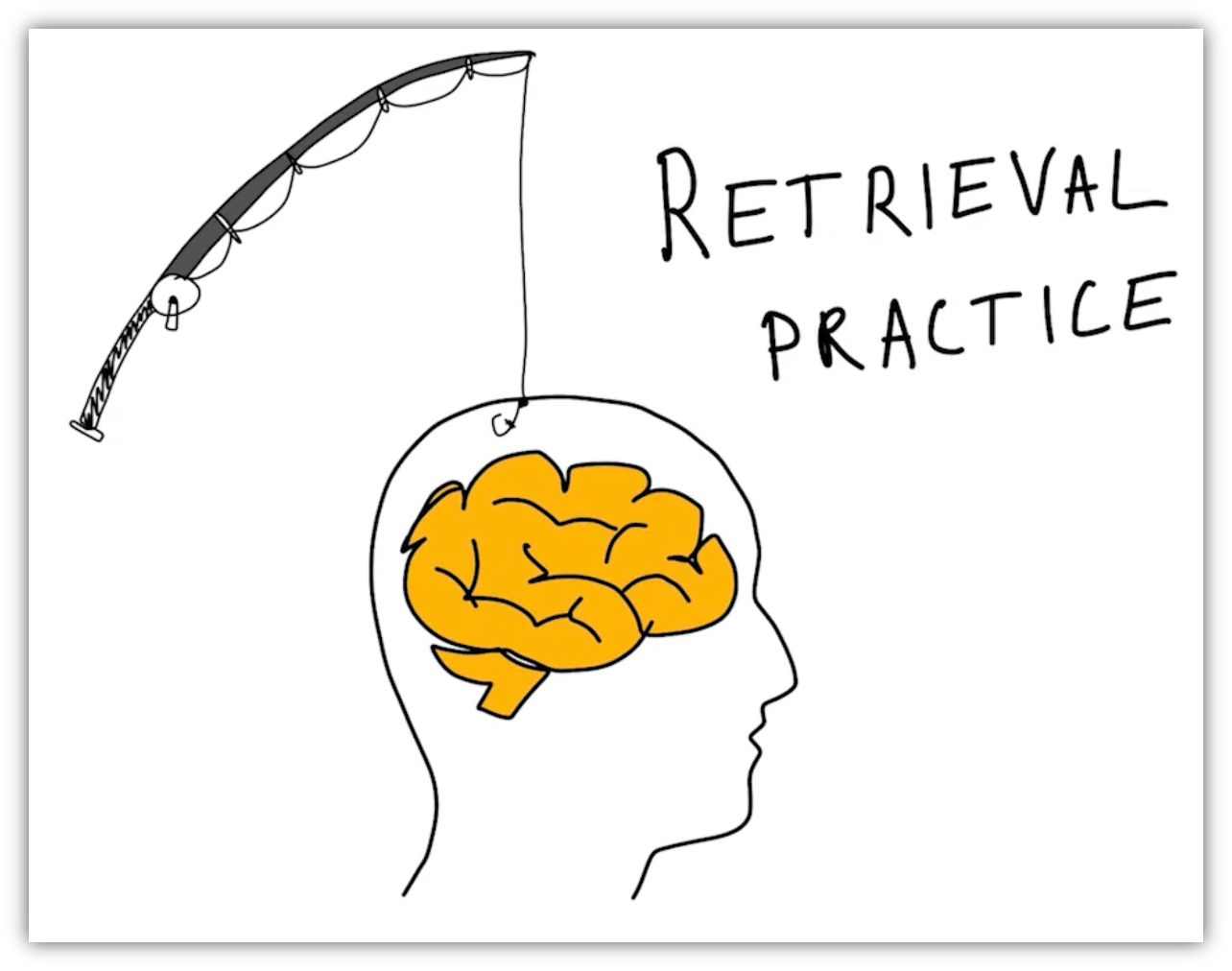

This means that students must mentally hold onto different, seemingly unrelated pieces of information, and make

sense of them once the definition appears. This process is challenging for second-language learners, especially if

their working memory is already occupied with interpreting unfamiliar words. What makes this harder is that

colour blindness is not commonly discussed in the Indian context. Another such cultural disconnection occurs at

the section in the story when a student asks Mr. White, “How can you tell if a woman gets shy and blushes?” This

line only makes sense if the reader understands both what blushing looks like and that colour blindness would

make noticing a blush impossible. But is ‘blushing’ part of a typical Grade 6 Indian student’s vocabulary? Do they

know what it looks like, or what its social meaning is?

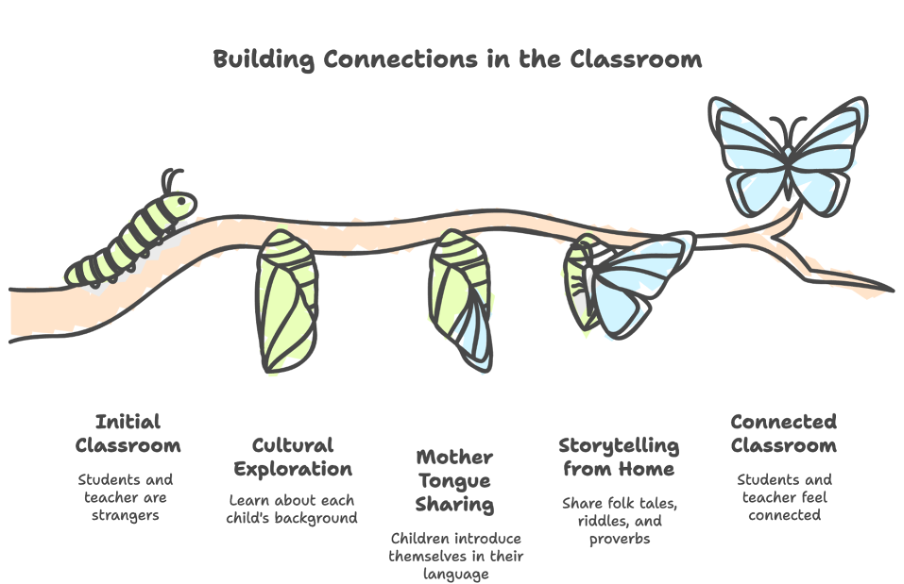

Research by Steffensen, Joag-dev, and Anderson (1979), Johnson (1981), and Carrell (1981a) shows that the

cultural background of the text interacts with the reader’s own cultural background, helping them form a mental

picture of the text. Additionally, in cases where the cultural context of a text was unfamiliar, students found it

much harder to read and understand than a text that was grammatically equivalent, but from a familiar context.

The Mr White passage, then, is challenging on all fronts: vocabulary, sentence structure, and cultural context.

Therefore, it puts a heavy load on students, since they have to understand word meanings at both the word and

sentence level. This leaves them with no resources to connect the paragraphs to each other. This story, therefore,

teaches us that we need to consider both the grade-appropriateness of a passage’s vocabulary, and more

importantly, the appropriateness of the action it asks the student to take.

How Can We Design Reading for Understanding?

For educators selecting reading comprehension material, then, the insights from this experience offer a few important considerations. These are elements to keep in mind in addition to the important (but not sufficient) process of adding meanings to difficult words, simplifying complex sentences, and adding context for unfamiliar terms. Educators must:

- Think about whether the context of the story is one your students are likely to recognise and relate to.

- Identify concepts, actions, or social references that may be culturally unfamiliar—like “blushing”—and consider how those might affect comprehension.

- Pay attention to when critical information is presented in a passage. If it comes too late, it may place a heavier load on students’ working memory, especially for second-language learners.

- Ask yourself what assumptions the text makes about the reader’s background knowledge, and whether those assumptions are valid for your students.

The invisible challenge (and opportunity) lies in the relationships between language and its usage, between vocabulary and its context. It lies between what the text assumes and what the reader brings to it. For educators, recognising this means moving beyond surface-level readability, and paying close attention to how meaning is used and applied to the world around us. That’s where true accessibility lies.

Glossary

- self-guided – a learning approach where students work through material on their own, without real-time support from a teacher

- readability indices – tools that measure how easy or difficult a text is to read, often using factors like sentence length and word difficulty

- working memory – a type of short-term memory used to hold information temporarily while using it to perform a task, like reading something new

- grade-appropriateness – whether the content, vocabulary, and structure of a passage are suitable for students at a certain grade level

Are these principles already part of your teaching toolkit?

We’d love to hear your story!

References used in the article:

- Carrell, P. L. (1981). Culture-Specific Schemata in L2 Comprehension.

- Johnson, P. (1981). Effects on Reading Comprehension of Language Complexity and Cultural Background of a Text.

- Steffensen, M. S., Joag-Dev, C., & Anderson, R. C. (1979). A Cross-Cultural Perspective on Reading Comprehension.

Enjoyed the read? Spread the word

Interested in being featured in our newsletter?

Feature Articles

Join Our Newsletter

Your monthly dose of education insights and innovations delivered to your inbox!

powered by Advanced iFrame