Edition 13 | January 2026

Feature Article

Why Competency Based Training Isn’t Working:

The Learning Science Gap

One of the most persistent questions I encounter when discussing diagnostic reports with school leaders is a variation of this: “If my students scored low on this test, does it mean they do not know the concept at all?”

This question usually comes with a sense of disbelief. Teachers point to high school exam scores or the fact that they spent weeks on a specific chapter. They feel the test has somehow failed to capture the student’s true ability. Behind this frustration lies a fundamental misunderstanding of what a test is designed to do.

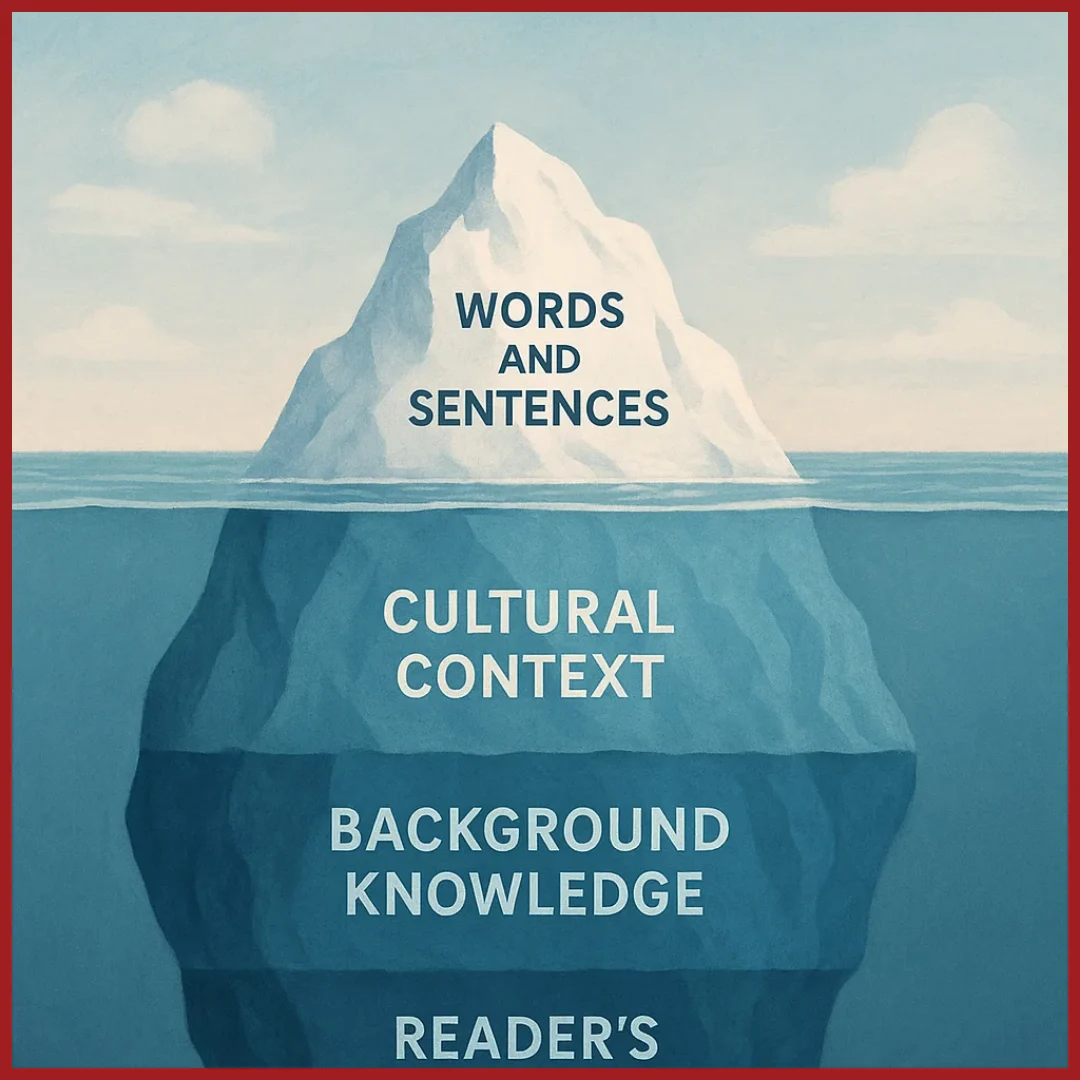

We often view a test as a bucket intended to catch every drop of a student’s knowledge. In reality, a test is a window. It can only show you a certain portion of the landscape at once. To understand why even top-performing students in traditional Indian classrooms sometimes falter on international-standard assessments, we have to look at the sampling principle.

The Science of the Spoonful

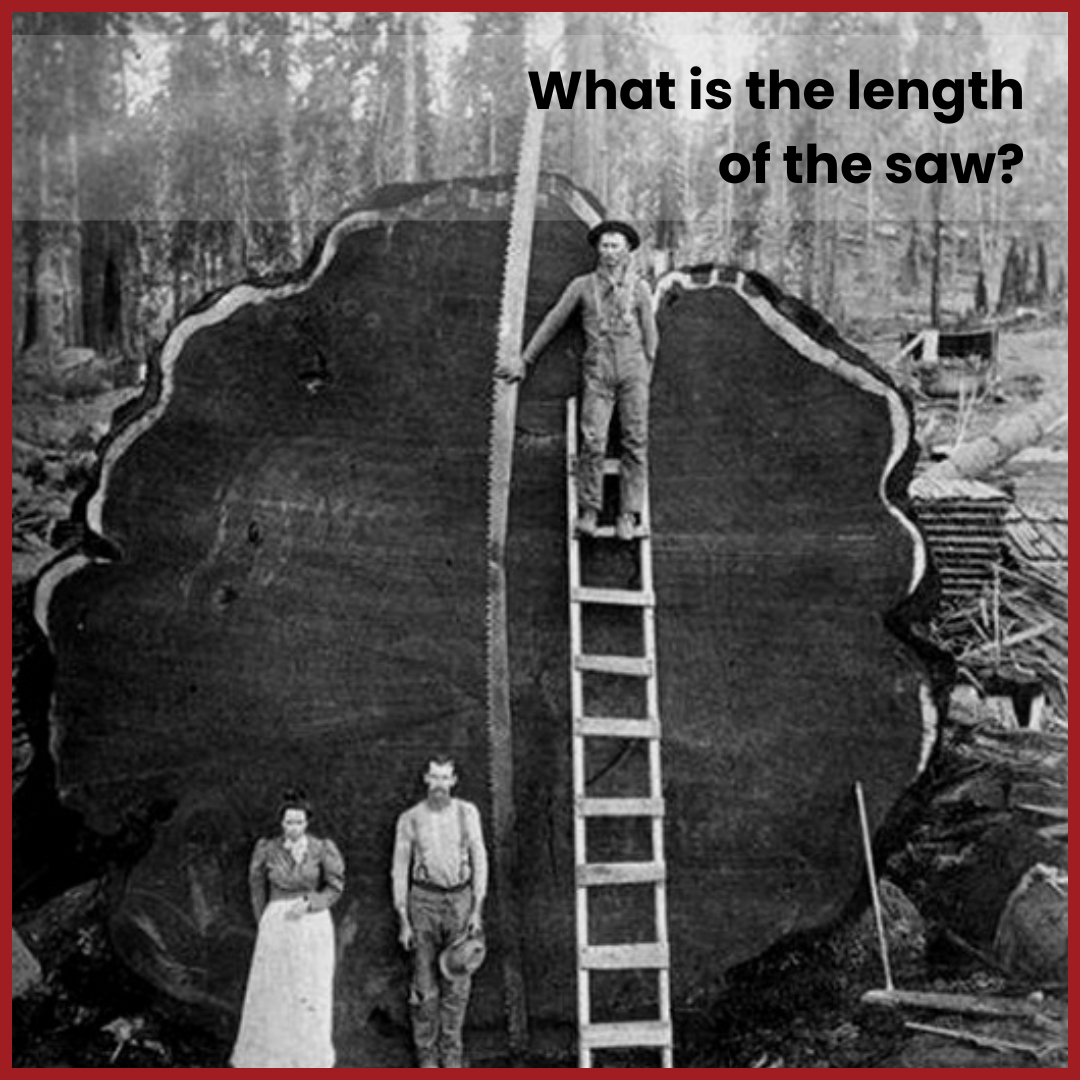

Imagine a chef standing over a large, steaming pot of sambar. The chef does not drink the entire pot to check the seasoning; they take a single spoonful. For that spoonful to be a valid representation of the whole pot, two things must happen: the soup must be stirred well, and the spoonful must be taken carefully.

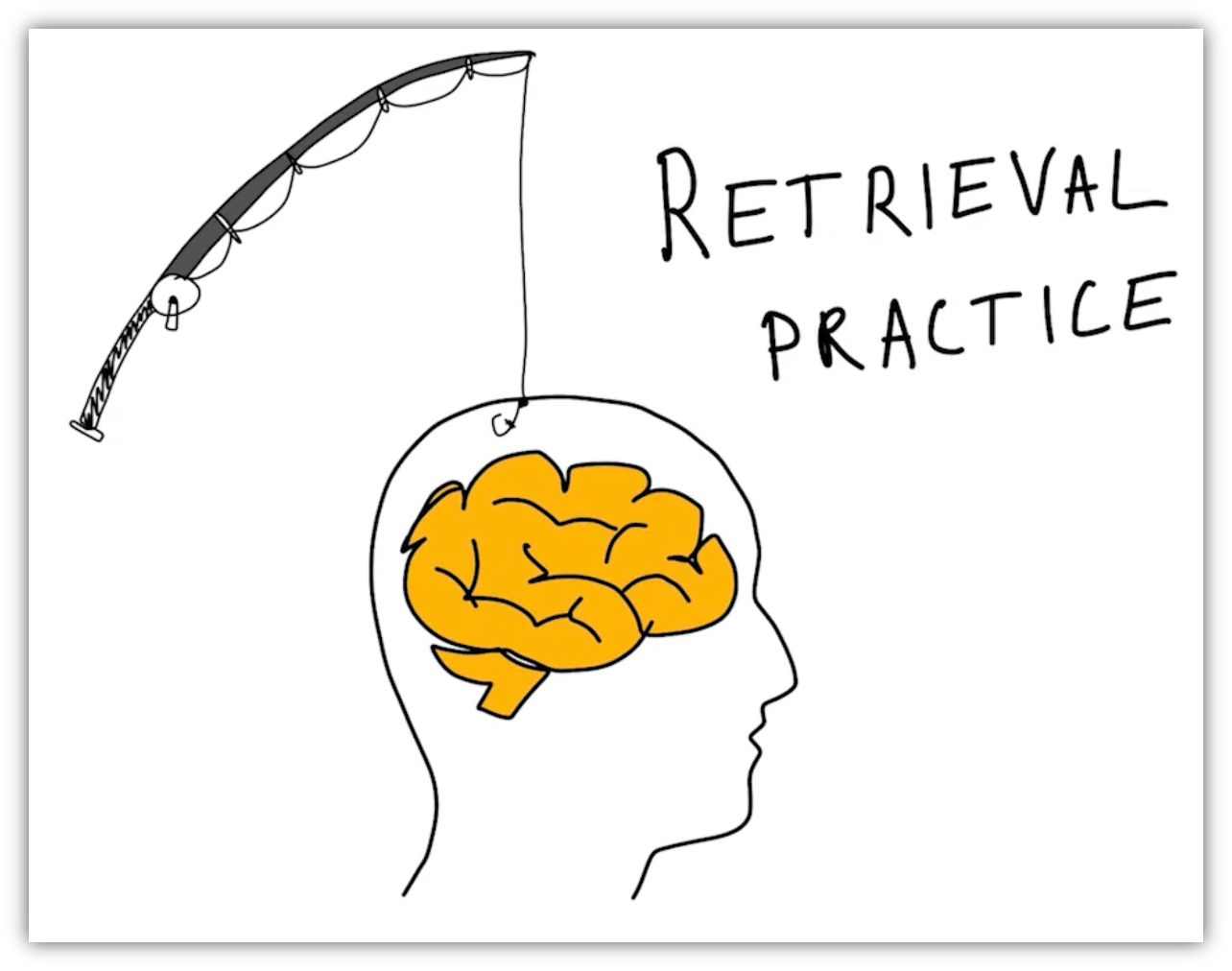

In the world of educational measurement, the soup is the entire domain of a subject, like Number Sense or Scientific Literacy. The spoonful is the test. Because we cannot ask a student a thousand questions to cover every possible permutation of a concept, we must choose a representative sample. A high-quality assessment is not a checklist of everything taught; it is a diagnostic tool designed to uncover how well a learner can transfer their understanding to unfamiliar contexts.

Professor Daniel Koretz from Harvard famously explained this through what he calls the sampling principle. He argues that test scores reflect a small sample of behaviour and are valuable only insofar as they support conclusions about the larger domains of interest. A failure to grasp this principle is at the root of widespread misunderstandings of test scores.

The Gap in the Indian Classroom

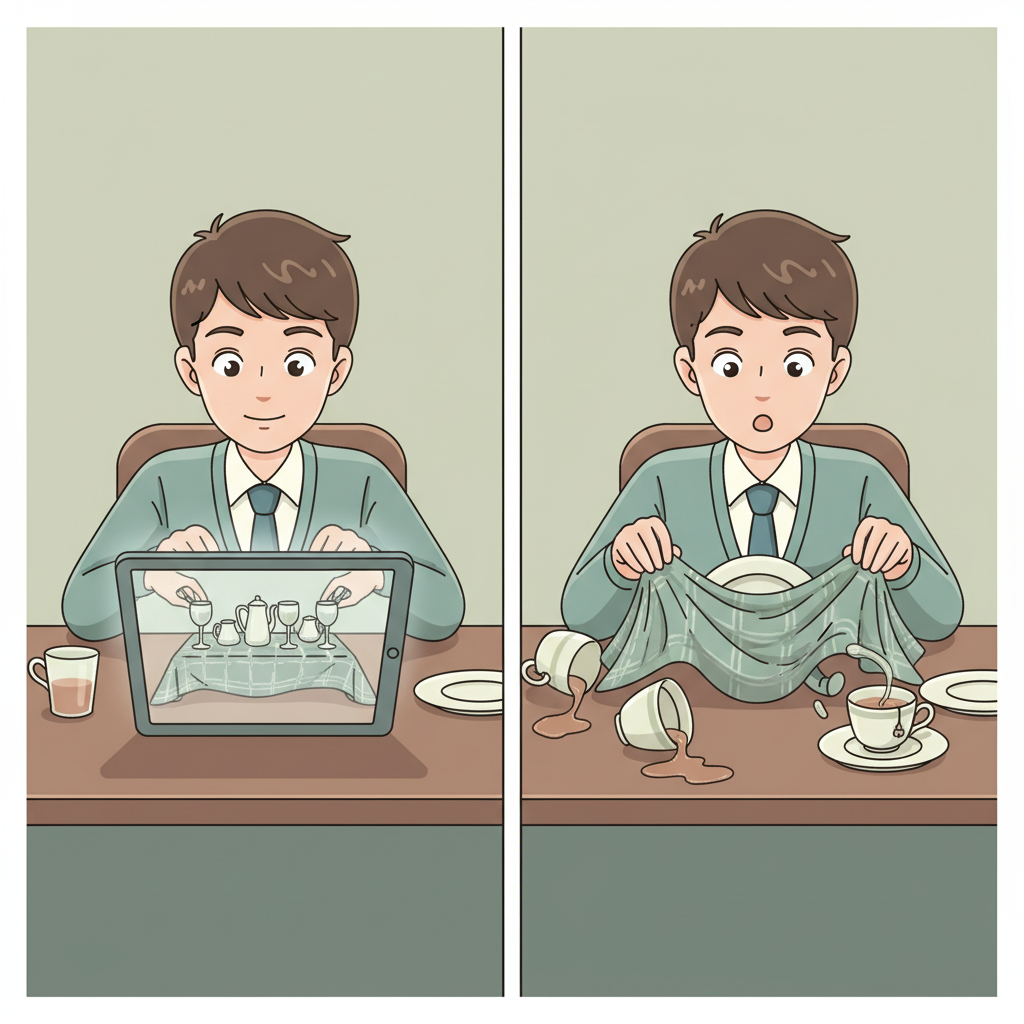

In many Indian schools, the traditional school exam is less of a sample and more of a mirror. It often reflects the exact problems found in the back of the textbook or the specific examples shared in class. When a test merely asks a student to reproduce what was seen in a familiar context, it is not sampling the domain of understanding; it is sampling the student’s memory.

When students transition from these internal exams to a diagnostic assessment, the nature of the spoonful changes. The questions shift from recall to application. The ‘stirring of the soup’ becomes evident. If a student has only learned to solve problems that look exactly like the ones in the book, they struggle when the ‘sample’ comes from a slightly different angle.

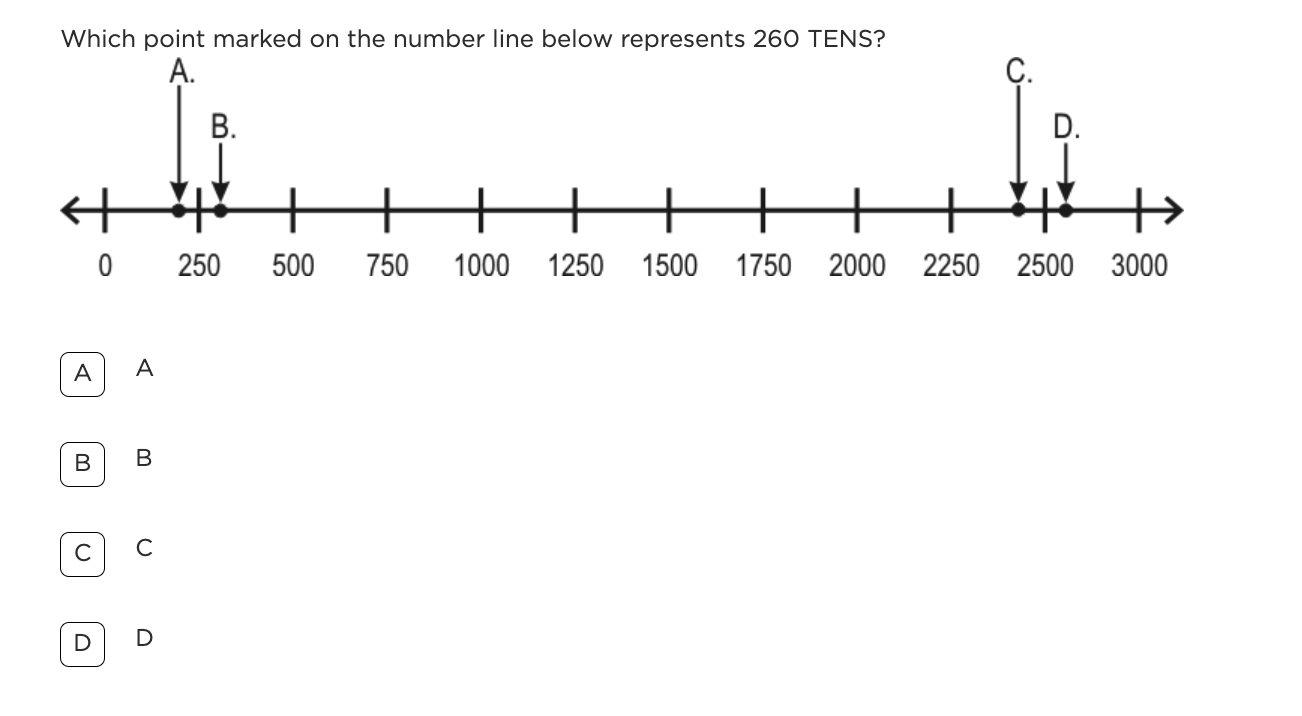

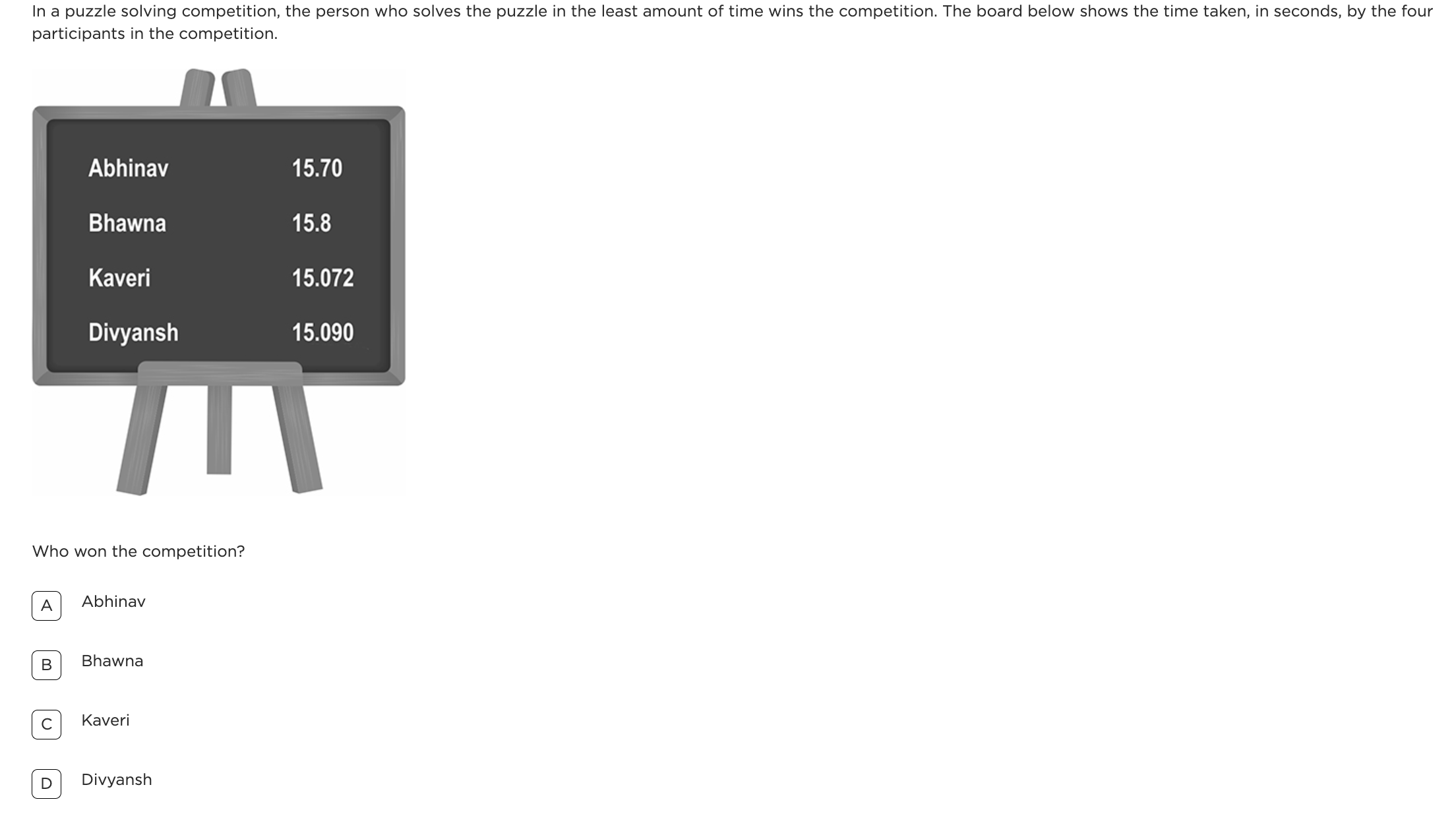

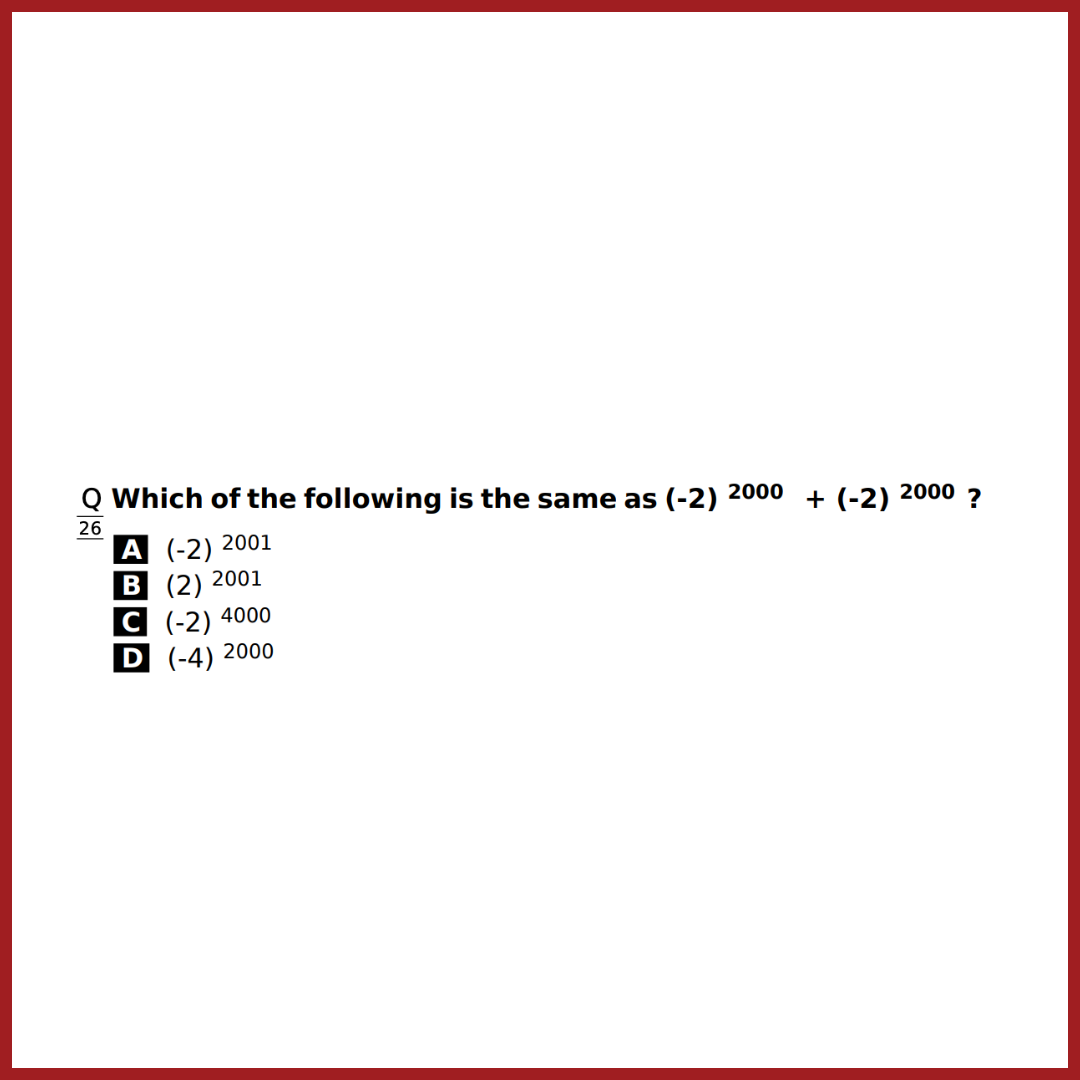

Let us look at how this sampling works across three core domains:

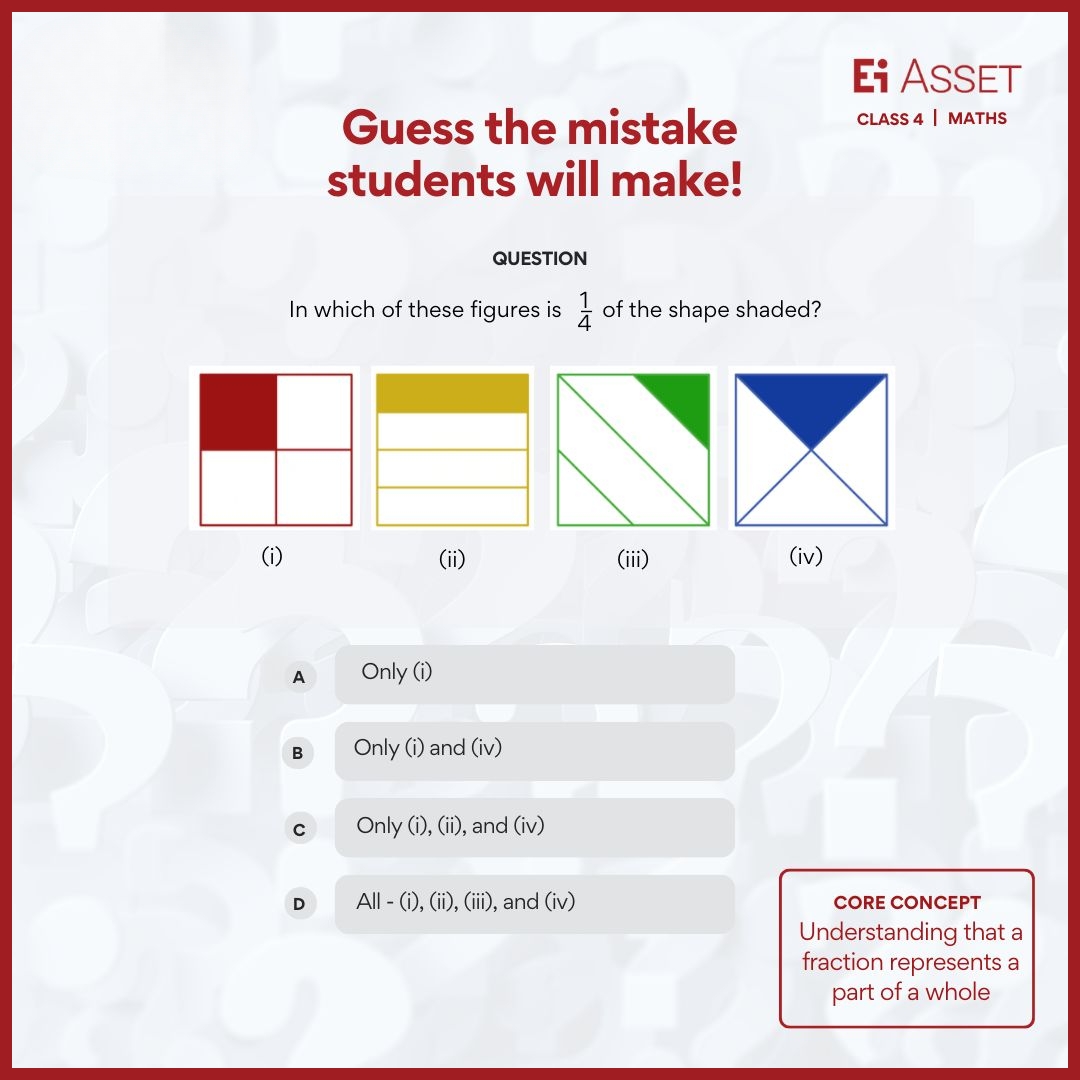

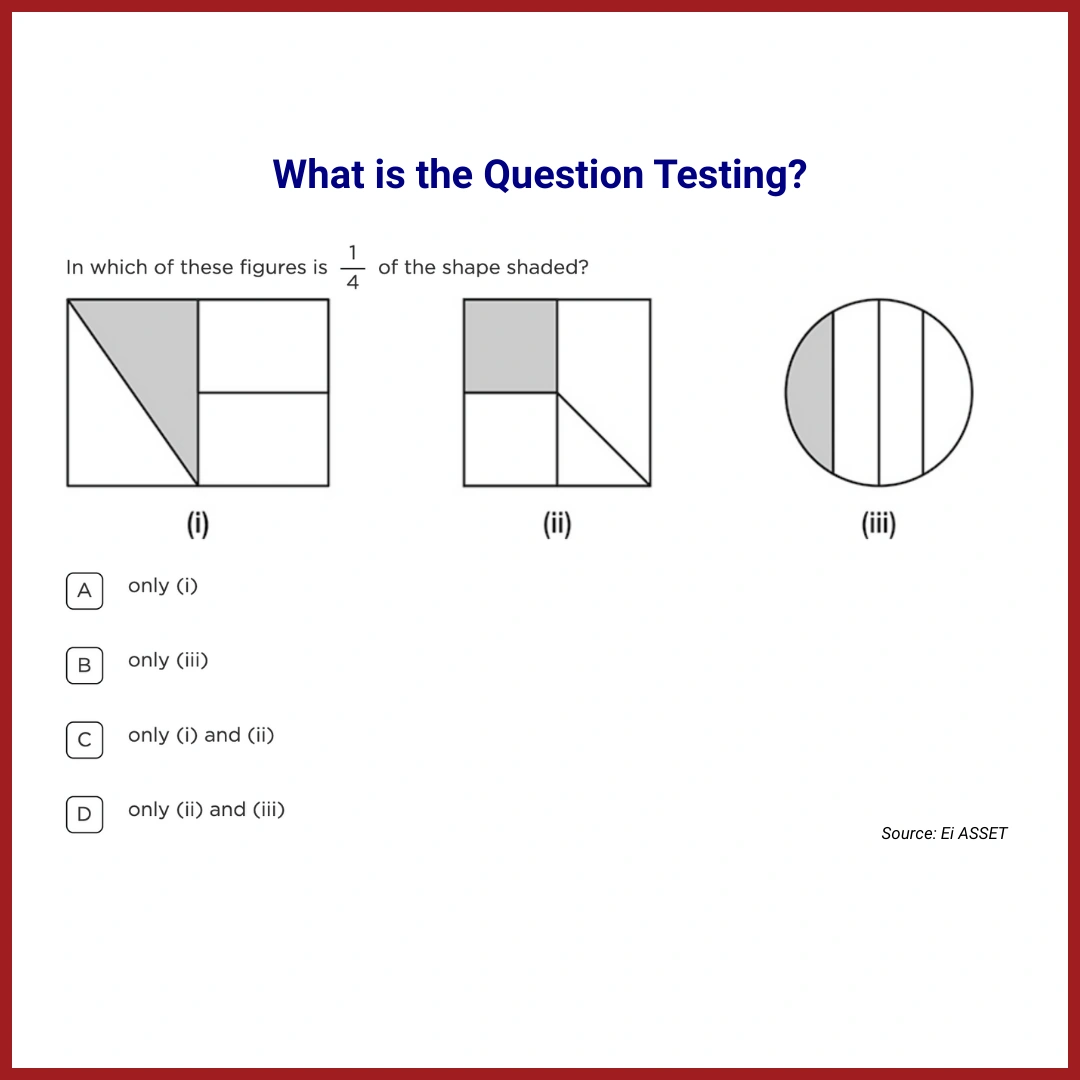

Mathematics and the Magnitude of Fractions A typical school exam might ask a student to add 3/4 and 2/3. Most students will mechanically find a common denominator and produce the answer. However, a diagnostic item might ask a student to estimate where 3/4 sits on a number line relative to 2/3. If a student can calculate but cannot visualise the magnitude, i.e. the size of the parts they lack Number Sense. The test has sampled a deep conceptual gap that a standard calculation would never reveal.

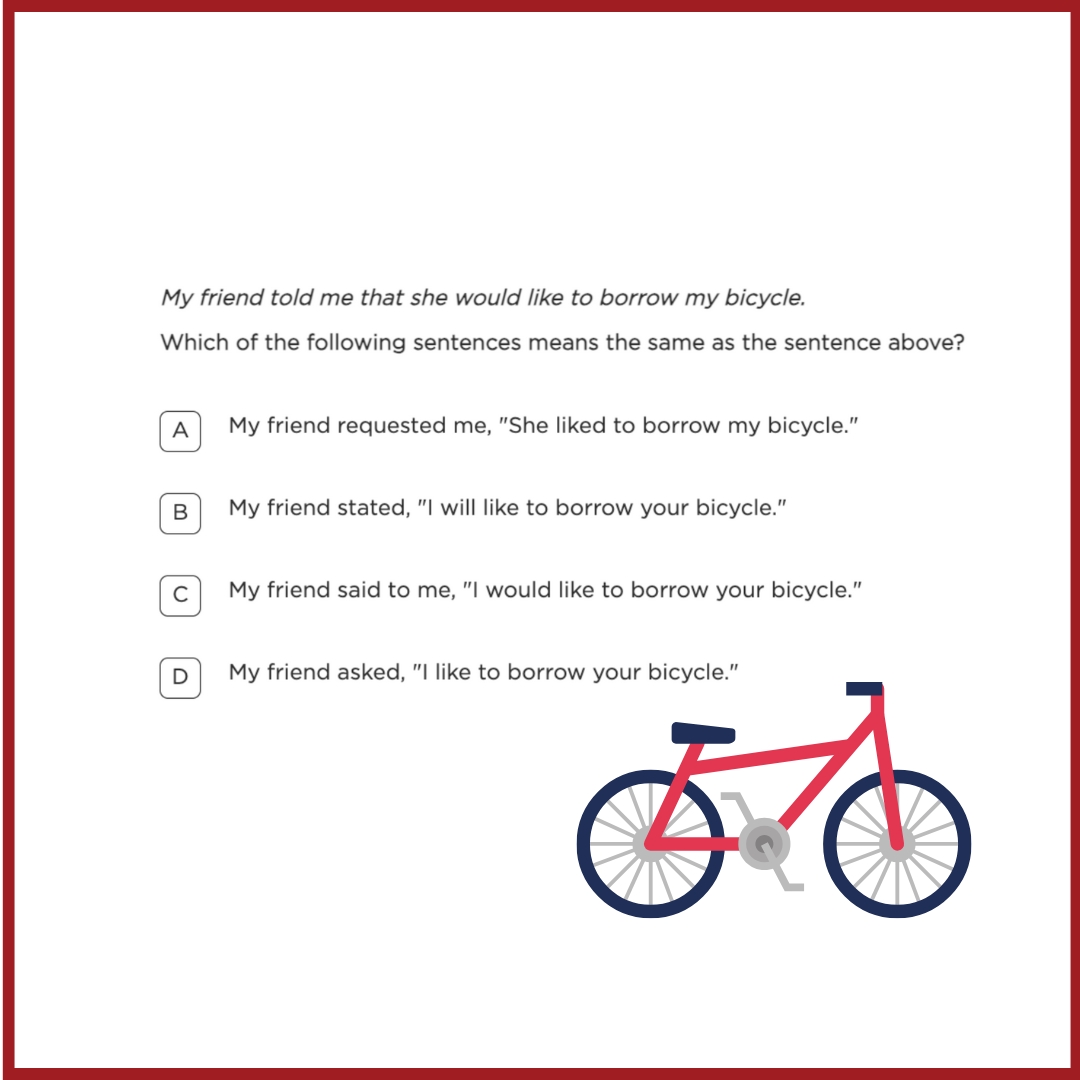

English and the Nuance of Context Consider the sentence: The atmosphere in the room was charged. A recall-based test might ask for the definition of the word atmosphere. A diagnostic test samples the student’s ability to interpret context, asking what the word charged implies in this specific scenario. Knowing the dictionary definition is irrelevant if the student cannot trace how context shifts meaning, a skill vital for navigating complex real-world texts.

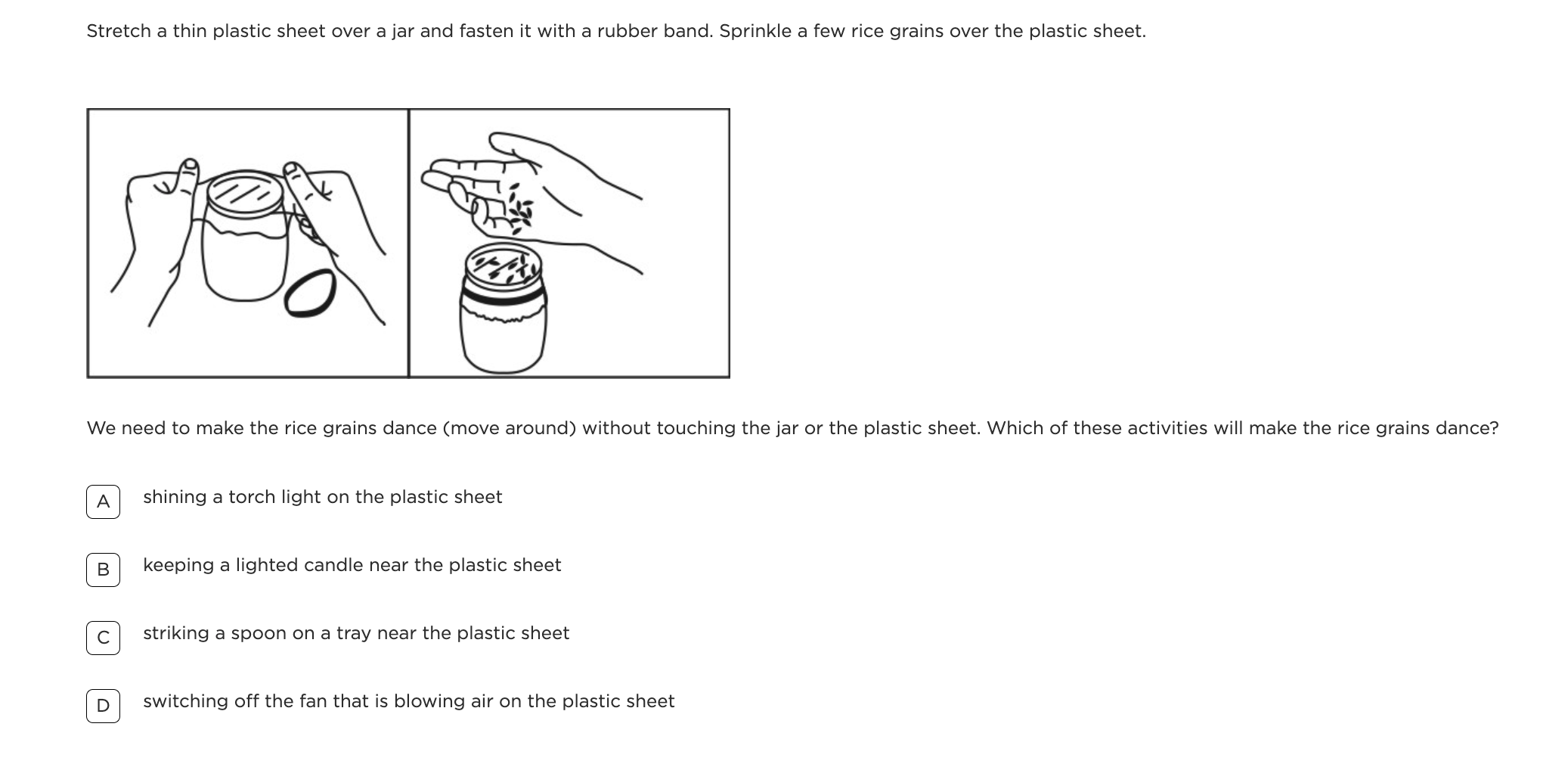

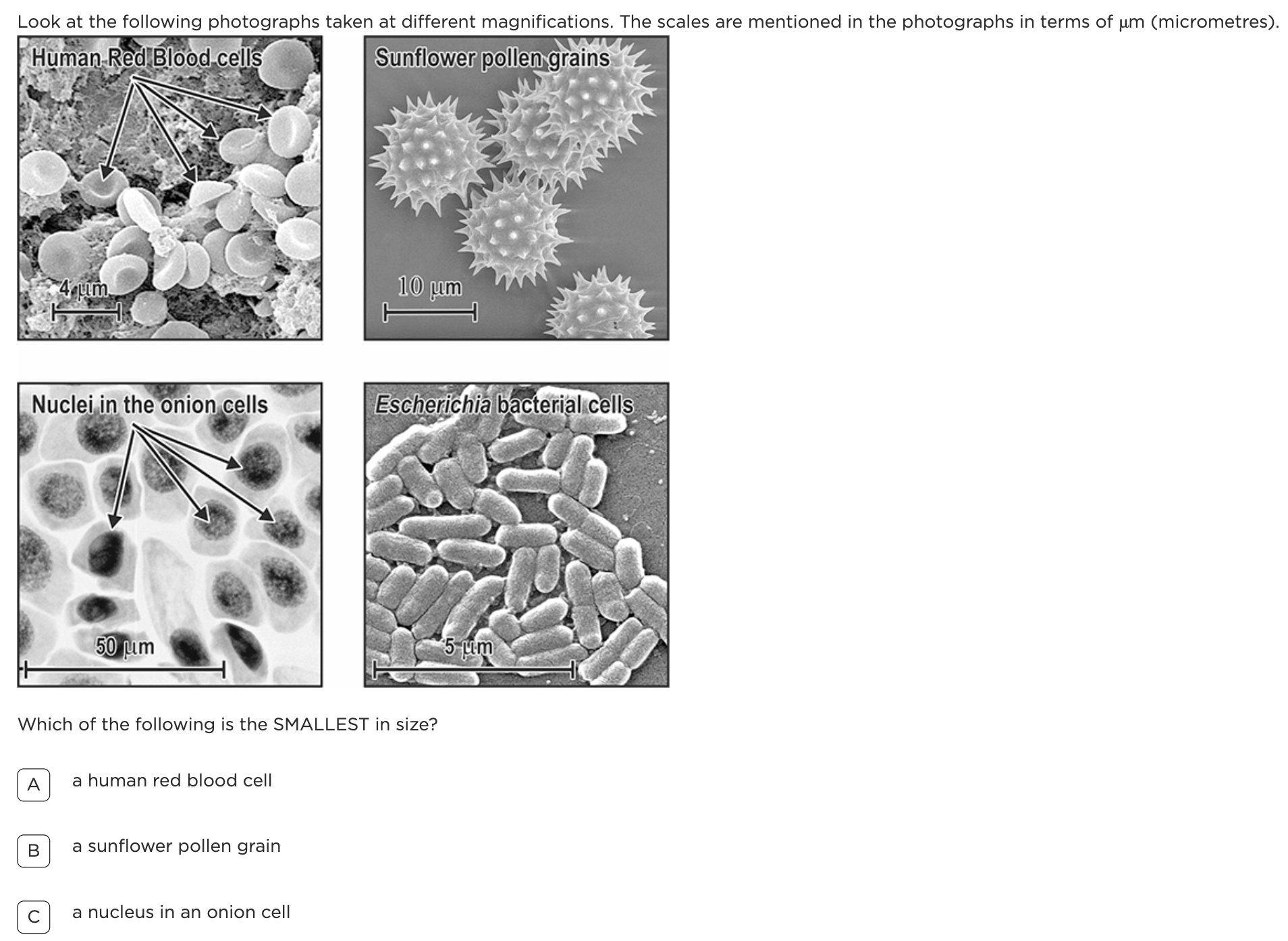

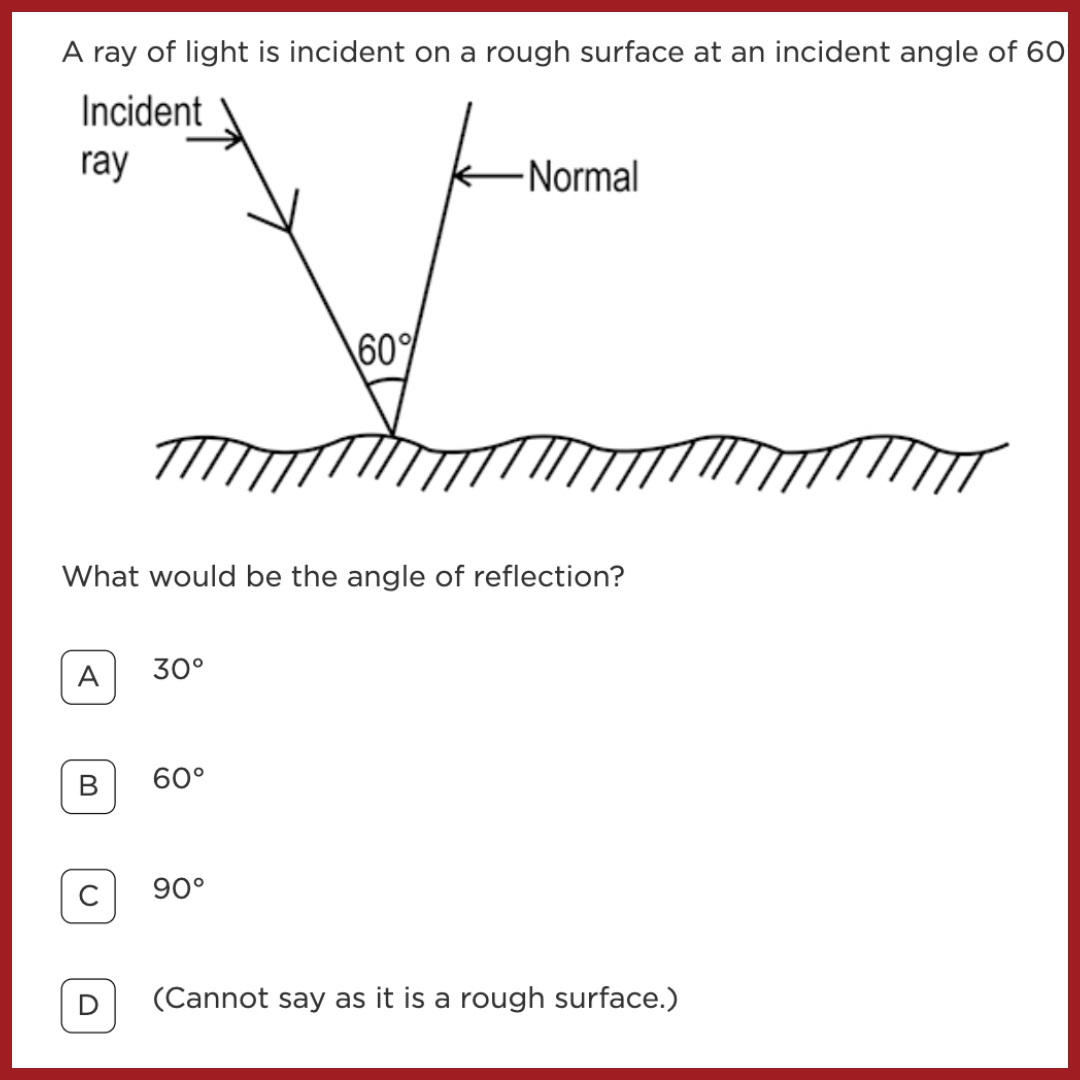

Science and the Logic of Variables In Science, we often see students who can recite the formula for the time period of a pendulum. But if an item asks what happens to that time period if the mass of the bob is doubled, many will struggle. This question samples the student’s ability to isolate variables and apply a principle to a new situation. It moves the focus from the formula to the underlying scientific reasoning.

The Risks of Misinterpreting the Sample

When we fail to grasp that tests are samples, we inadvertently create a narrowing of the curriculum. If teachers believe the goal of a test is to cover specific, predictable question types, they begin to teach to those types.

This results in a phenomenon called superficial mastery. Students appear brilliant when the questions stay within the safe harbour of familiar patterns. But the moment they face an item that samples the ‘deep water’ of the domain, the reasoning and the transfer, then their scores dip. This dip is not a sign that the student knows nothing; it is a signal that their knowledge is fragile and transfer is the litmus test for understanding.

Misunderstanding the sample also leads to misreading the data. A rise in scores might not mean students are smarter; it might just mean they have become better at spotting the patterns in the sample. Conversely, a dip in scores isn’t always a failure of teaching, it might be that the test sampled a level of cognitive demand that the classroom has yet to reach.

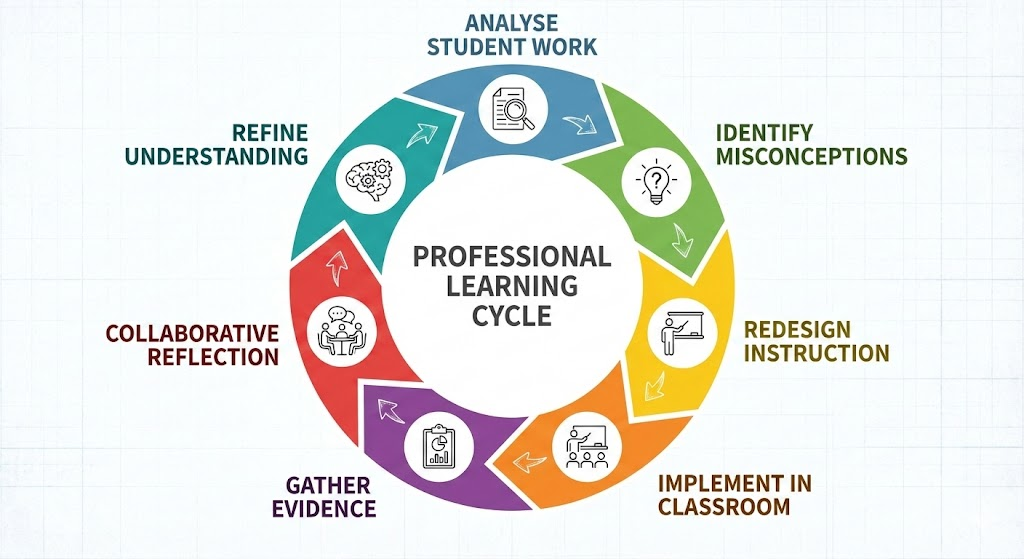

A Roadmap for School Leaders: Moving from Coverage to Mastery

Moving toward a more sophisticated understanding of assessment requires a shift in how we lead our academic departments.

Move Beyond Chapter Coverage: Encourage educators to look at Skill Mapping”rather than just Portion Completion. If a student has finished the chapter on Electricity but cannot troubleshoot a basic circuit diagram they have never seen before, the chapter is not truly mastered.

Treat Errors as Diagnostic Data: In a standard exam, an error is a lost mark. In a diagnostic assessment, an error is a data point. It tells you exactly where the stirring of the soup failed. Use these insights to adjust teaching mid-stream, rather than waiting for the end of the year.

Interpret Test Data as Feedback, not Verdict: A student’s error points to where understanding breaks down. The goal is not to judge but to diagnose. When teachers see a low score on a sampled skill, the conversation should shift from “Why did they fail?” to “How can we stir this part of the soup better?”

Build Assessment Literacy: We must help our teachers understand that a hard question is not one that is obscure, but one that requires a higher level of cognitive demand. When teachers understand why good assessments sample, they stop chasing coverage and start focusing on representation.

The Carefully Chosen Spoonful

The value of research-based diagnostic tools lies in the rigour of their sampling. Every question is designed as a high-resolution window into a specific skill. These items are calibrated to ensure they are fair, reliable, and truly representative of the domain.

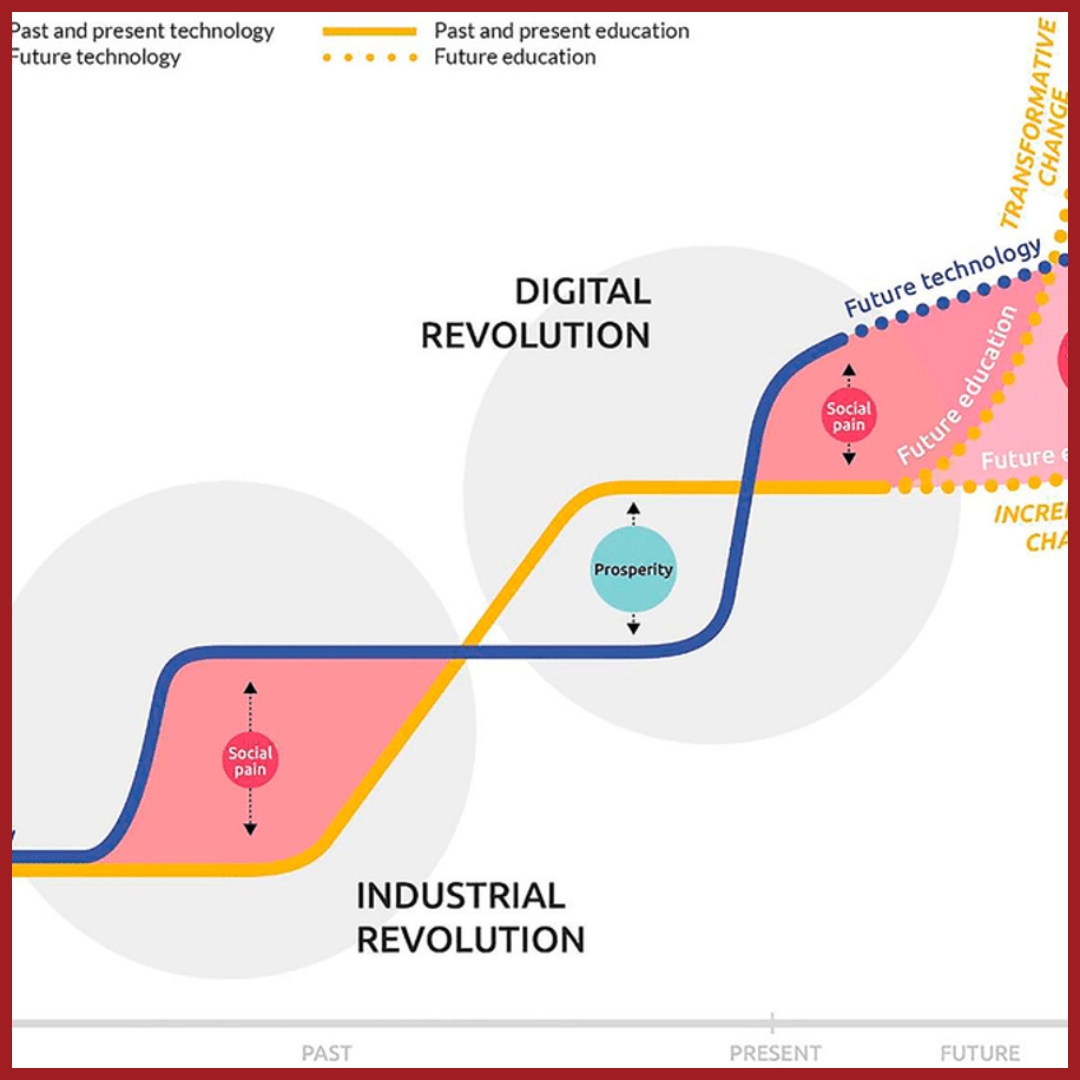

As we move toward the goals laid out in the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, the focus in India is shifting decisively toward competency-based assessment. This is, at its heart, a move toward better sampling. It is an admission that knowing the facts is no longer enough; our students must be able to navigate the unknown.

A test is never a final verdict on a child’s potential. It is a snapshot of their current ability to transfer what they have learned. Our task as educators is not to help students memorise the spoon, but to ensure the soup is stirred so well that they can handle whatever sample the world eventually takes.

If we teach for depth, variety, and reasoning, our students will not fear the test. They will see it for what it is: a mirror that reflects their own growing capacity to think for themselves. After all, each serving of the well stirred spoon tells us an important story every time. With good diagnostic assessments, we don’t look out for verdict of complete understanding or no understanding, but insights which can feed forward the curriculum, students learning and our teaching plans.

Note: If you liked the article and want to use it in your next staffroom meeting, please find a visual story of the article below.

Diagnostic Assessments Are Samples - Not the Syllabus

Are these principles already part of your teaching toolkit?

We’d love to hear your story!

Enjoyed the read? Spread the word

Interested in being featured in our newsletter?

Feature Articles

Join Our Newsletter

Your monthly dose of education insights and innovations delivered to your inbox!

powered by Advanced iFrame