Edition 06 | June 2025

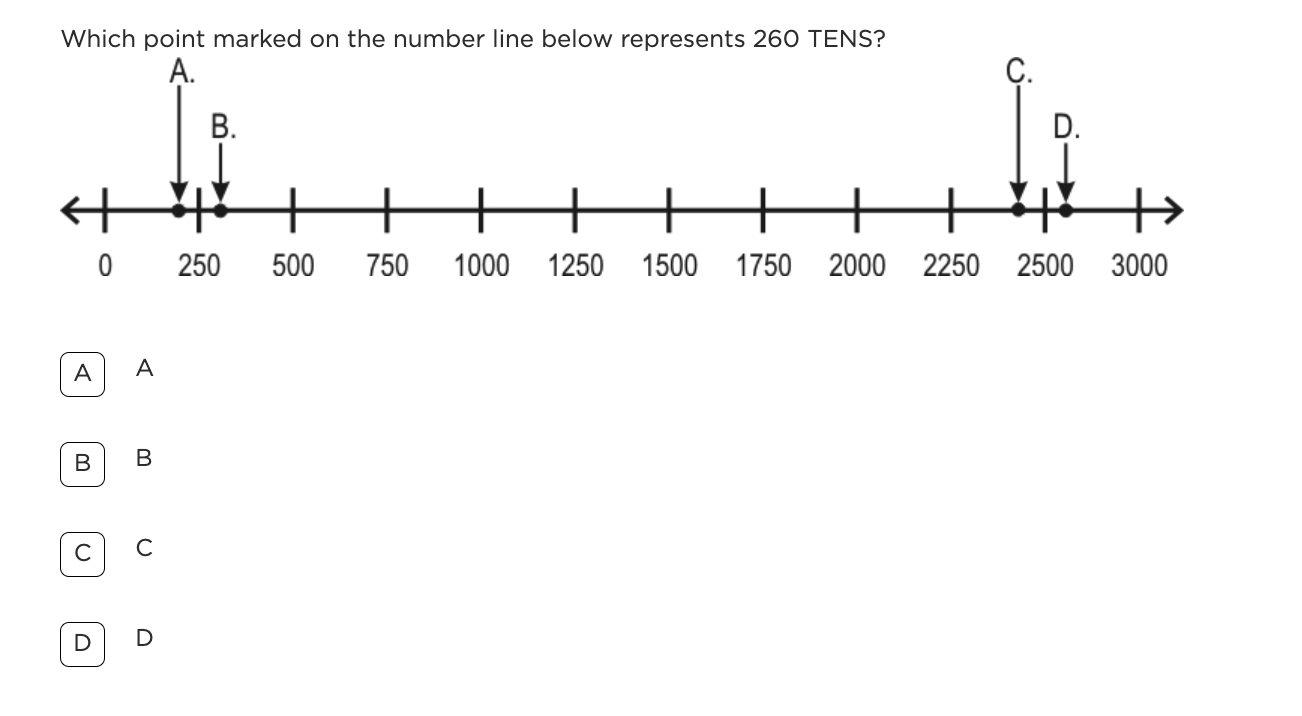

Educators Speak: Sr. Academic Head

Raymond Fernandes

Raymond Fernandes brings over 30 years of education expertise as Senior Academic Head at Global Schools Foundation. Global Schools Foundation has over 64 schools spread across 11 countries and subscribes to over 10 different curriculum frameworks. Previously serving as Chief Academic Officer at Singhania Education Services and President at Secure Learning, he has led curriculum development across prestigious institutions including Shiv Nadar School and EuroSchool International. A published science textbook author, Mr. Fernandes holds a Master’s in Education from the University of Bath, UK, and a Chemistry Honours degree from St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai.

Q1. You have led academic initiatives across diverse institutions (from established schools to new ventures). What have you learnt about leading change in education?

Education is a field of constant evolution—a reality I’ve experienced throughout my career. From established institutions to new ventures, I’ve learned that successful change leadership in education requires deliberate strategy and deep understanding of the human elements involved.

My Learnings

Education professionals often demonstrate a paradox—they prepare students for a changing world while sometimes resisting changes to their own practice. This resistance isn’t illogical; it stems from legitimate concerns about student outcomes and professional identity. I’ve learned to recognize that when teachers push back, they’re often advocating for educational values they deeply believe in.

The most transformative insight in my journey has been my guiding principle: “Set up everyone to succeed.” This means designing change processes where each stakeholder—teachers, students, parents, and administrators—can see a pathway to personal and collective success.

My experience across diverse institutions has revealed several essential strategies:

Build a compelling case for change: Educational communities need to understand not just what is changing, but why. When implementing standards-based assessment in an established school, I discovered that sharing research and connecting the change to our core mission created more buy-in than executive mandates ever could.

Differentiate support for different adopter types: Just as we differentiate for students, change leaders must recognise that the faculty need varied support. Early adopters need freedom to innovate, while those more hesitant benefit from structured guidance and opportunities to observe success.

Balance urgency with patience: Educational change requires a delicate balance creating momentum while allowing time for adoption. When introducing technology-integration change, a phased implementation with clear milestones must be maintained to ensure progress and preventing overwhelm.

Leading change has taught me to anticipate and address specific challenges:

Cultural legacy tensions

Educational institutions carry strong traditions that can collide with innovation. Honouring

institutional heritage while evolving practices requires intentional bridges between past and

future.

Resource constraints

Change initiatives often face a time crunch, training resources, and competing priorities. I’ve

learned to secure dedicated resources before launch and protect implementation time against the

whirlwind of constant demands of daily school operations.

Measuring impact meaningfully Educational changes require assessment beyond immediate metrics. School leaders often judge

initiatives by convenient metrics like test scores or NPS scores, missing deeper educational value.

One must develop balanced assessment frameworks combining quantitative and qualitative

measures, track longitudinal impact, and value growth in both non-academic competencies and

academic outcomes.

Ultimately, I’ve learned that educational change is most successful when approached not as a

technical challenge but as a deeply human endeavour. The most effective change happens not

through directives but through collaborative journeys toward shared goals—walking together

rather than leading from the front or pushing from behind.

The paradox of education is that while preparing others for change, we must embody it ourselves.

As academic leaders, our most powerful influence comes not from our strategic plans but from

our demonstration of being lifelong learners, embracing the very changes we advocate.

Q2. With India’s National Education Policy focusing on skill-based and multidisciplinary learning, what opportunities do you see for curriculum innovation in schools following the Indian curriculum?

The NEP 2020 represents a paradigm shift for Indian education, moving from rote learning toward

holistic development. As an academic leader, I see several strategic opportunities for curriculum

innovation within the Indian context:

Reimagining Content Organisation

The NEP’s emphasis on depth over breadth enables schools to restructure traditional CBSE and

ICSE syllabi into conceptual modules rather than chapter-based progression. I recommend

transforming conventional subject syllabi into integrated thematic units that draw connections

across disciplines. For example, science curricula could be organised around themes like “Energy

Systems” or “Material Sciences” that incorporate Physics, Chemistry, and Biology simultaneously.

Or In Humanities, particularly History, “Power and Governance Through Ages,” which provides an

opportunity to debate the structures to modern democracy, analysing patterns of authority,

representation, and resistance across different periods rather than studying these eras in

isolation. This approach will deepen understanding while reducing content redundancy across

subjects.

The NEP’s multidisciplinary focus creates three key innovation opportunities:

- Subject Integration:

Schools should develop learning modules that deliberately connect traditionally isolated subjects. For instance, creating units like ‘Mathematical Heritage of India’ that combine mathematical concepts with historical contexts and cultural significance would make both subjects more relevant to students. - Skill-Subject Fusion: Educational institutions should embed 21st-century skills directly into subject teaching rather than treating them as add-ons. Language curricula could incorporate communication, collaboration, and critical thinking as explicit learning objectives alongside traditional grammar and literature.

- Local-Global Connections: Schools would benefit from linking global competencies with local contexts and challenges. Environmental science curricula could connect global sustainability goals with local conservation initiatives that students can actively participate in.

- Teacher Development:Establishing professional learning communities focused on interdisciplinary teaching approaches and skill-based assessment

- Resource Adaptation: Redesigning textbooks and learning materials to support thematic and integrated learning

- Schedule Restructuring:Moving from rigid subject periods to more flexible learning blocks that accommodate project-based and interdisciplinary work

The NEP offers Indian schools the legitimacy to innovate curriculum in ways previously considered too experimental. The greatest opportunity lies in repositioning student agency at the centre of learning design—where students co-create learning pathways, set meaningful goals, reflect on their progress, and actively participate in assessment processes.

Through these innovations, schools can transform the Indian curriculum from content delivery into an experiential journey that develops both deep subject understanding and the essential capabilities needed for future success.Q3. How do you envision the role of assessments in driving meaningful learning?

- Competency Frameworks: Developing subject-specific rubrics that map skill progression across grade levels, allowing for more nuanced understanding of learning beyond marks.

- Portfolio Assessment: Implementing digital repositories where students can document projects, problem-solving processes, and reflections that demonstrate both subject mastery and skill application.

- Real-world Performance Tasks: Creating authentic assessments where students apply their learning to actual community challenges, evaluated by both teachers and relevant community stakeholders.

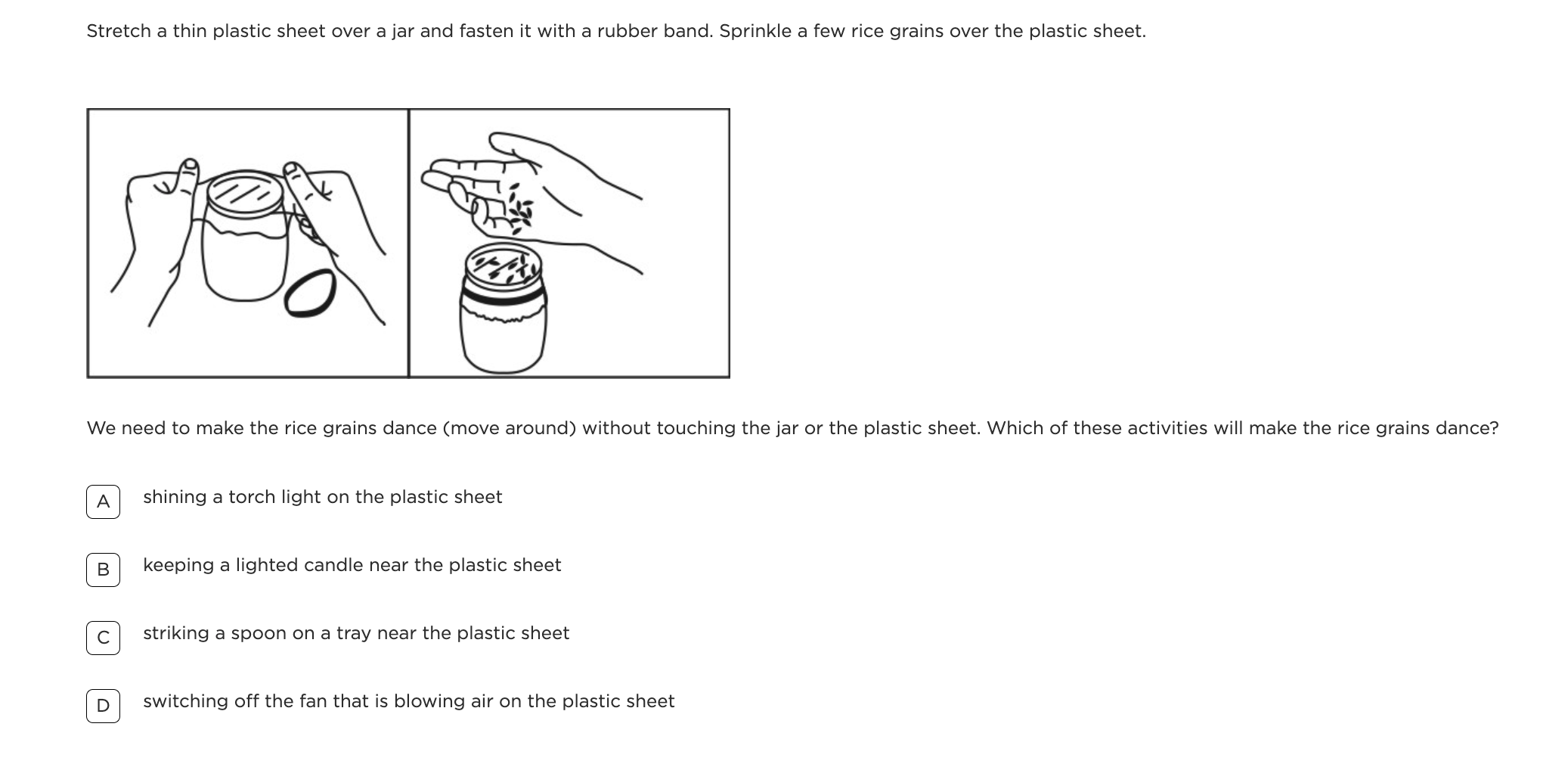

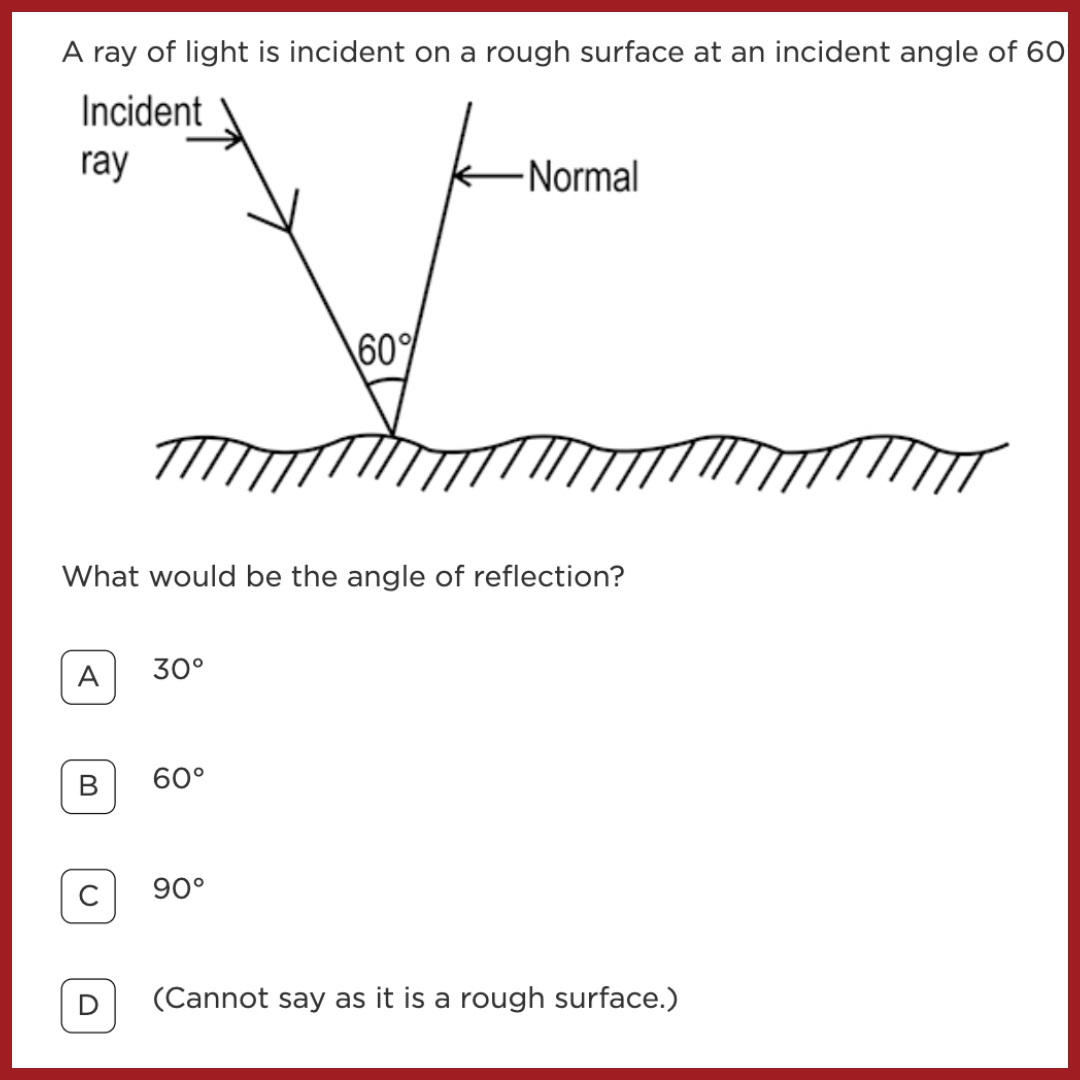

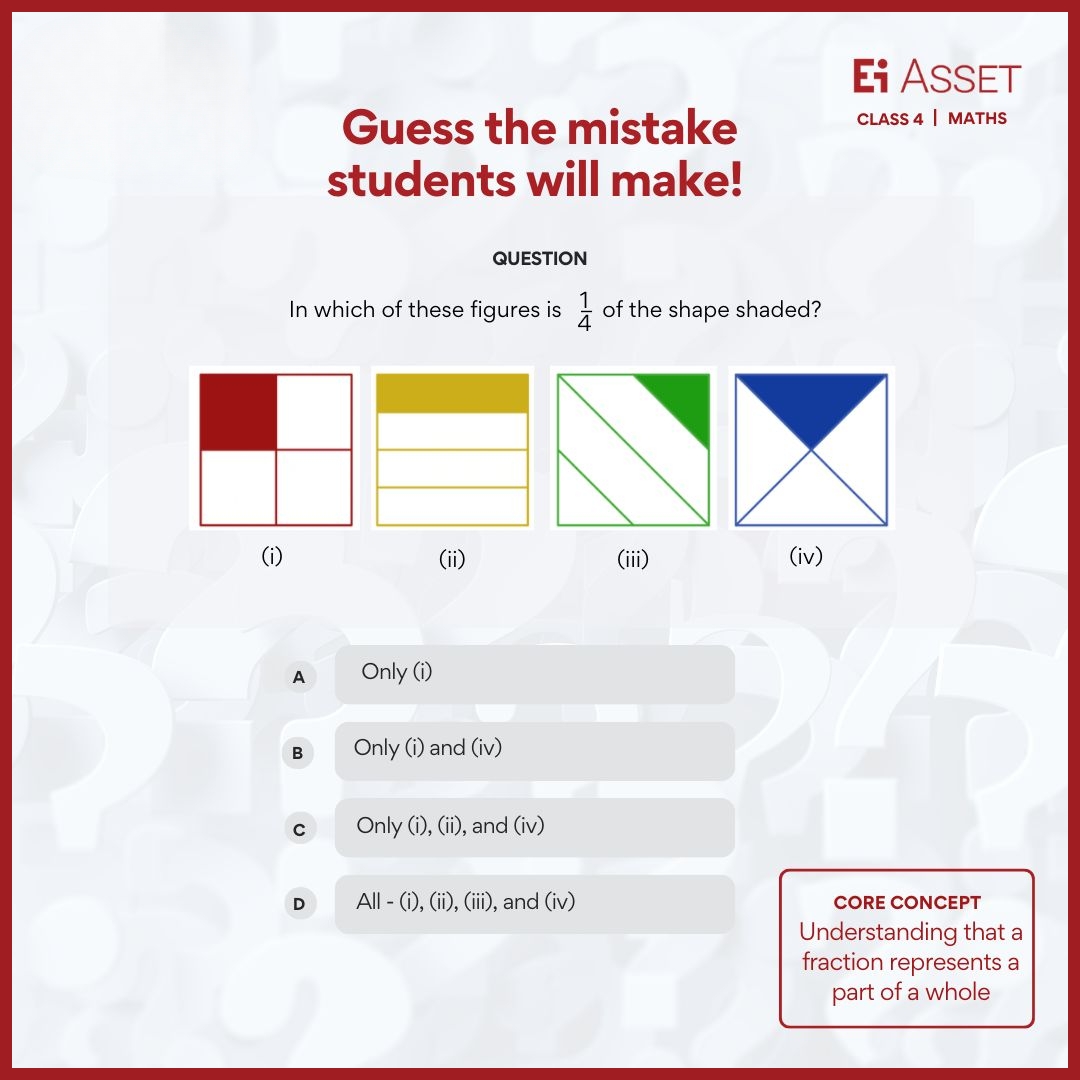

- Diagnostic Tools: Assessments should identify learning gaps and strengths, providing actionable insights for both teachers and students. For example, our schools now begin units with concept-mapping exercises that reveal students’ prior knowledge and misconceptions, allowing teachers to tailor instruction accordingly.

- Learning Experiences: Well-designed assessments themselves become powerful learning moments. When students engage in peer assessment of presentations using detailed rubrics, they simultaneously deepen their understanding of communication standards while developing critical evaluation skills.

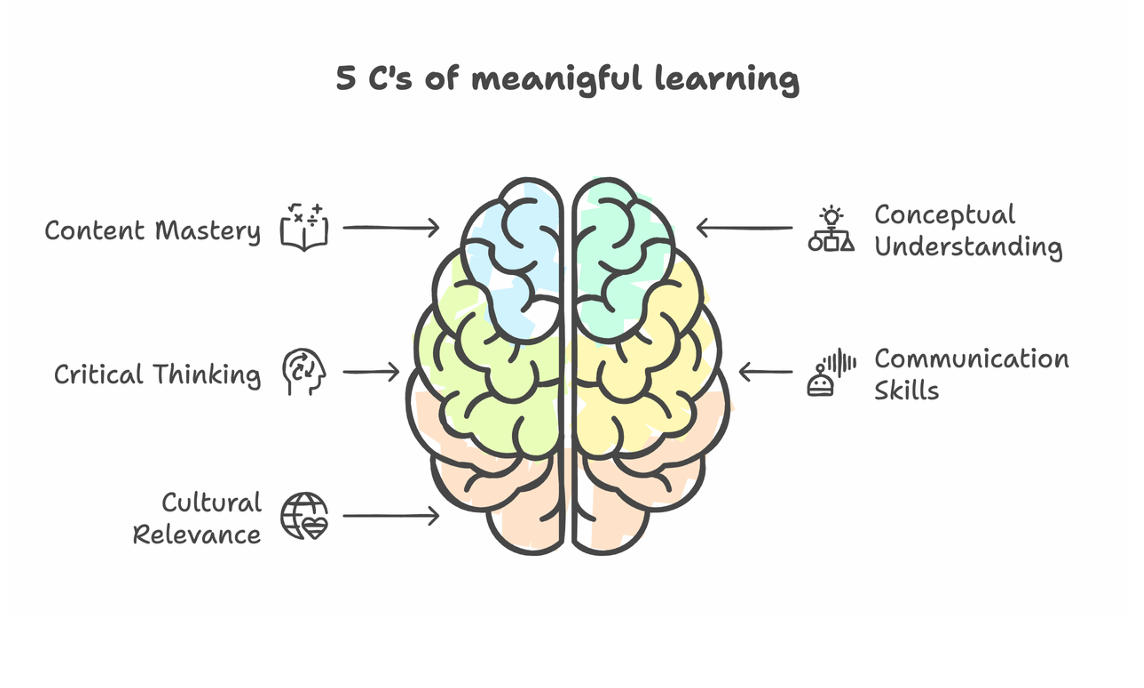

- Growth Documentation: Assessments should create a narrative of development across all five dimensions of meaningful learning. Our digital portfolios track student progression not just in content knowledge but in their ability to connect concepts across disciplines, approach problems with innovative thinking, and communicate with cultural sensitivity.

- Performance-Based Assessments: Real-world scenarios requiring application of knowledge and skills

- Project-Based Assessments: Extended investigations resulting in tangible products or solutions

- Technology-Enhanced Assessments: Interactive simulations, digital creation tools, and collaborative platforms

- Self and Peer Assessments: Structured reflection protocols that develop metacognitive abilities

- Formative Check-ins: Low-stakes, frequent feedback loops that guide learning in real-time

- Teacher Capacity: We should address this through dedicated professional development on assessment design and interpretation, focusing on one new assessment approach per semester.

- Time Constraints: Restructured the academic calendar to include designated “assessment for learning” days where students engage in meaningful assessment experiences without the pressure of covering new content.

- Reporting Complexity: The reporting system should include narrative components alongside traditional grades, using a competency-based framework that communicates growth across all five dimensions.

- Standardized Testing Requirements: Prepare students for external exams but be mindful of maintaining a comprehensive assessment philosophy by explicitly connecting higher-order thinking skills to exam success

- Technology Infrastructure and Digital Divide: Implementing tech-enhanced assessments requires adequate infrastructure across all schools. Disparities in student access to devices and internet both in school and at home create inequities. Schools must invest in on-site resources and develop alternative assessment pathways that maintain rigor while accommodating diverse access realities.

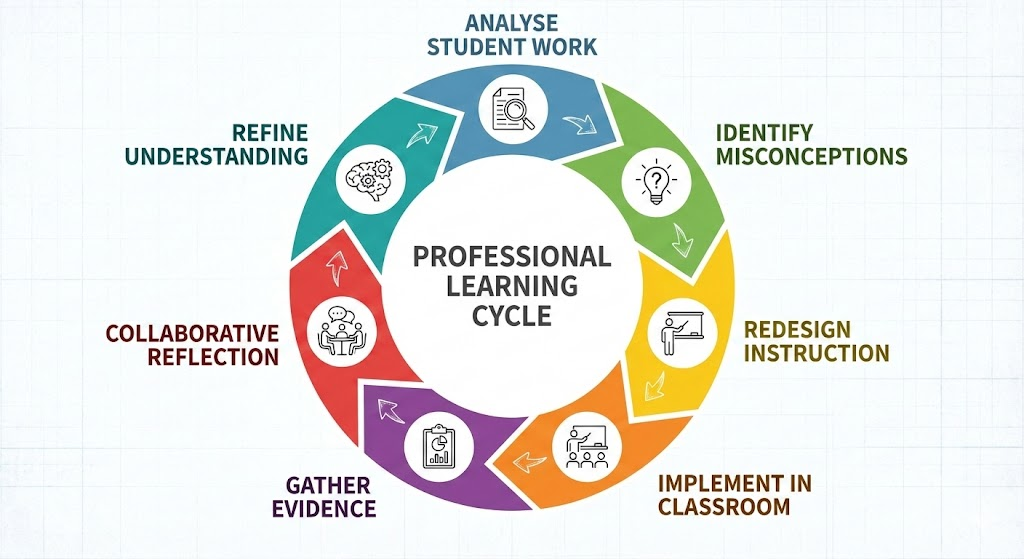

Assessments must be viewed as integral to the learning cycle—not as interruptions to it. They

should be meticulously designed, thoughtfully administered, and meaningfully reported. Like mile

markers on a journey, they help students recognize how far they’ve travelled intellectually and

emotionally, while also guiding them toward their next destination.

In our schools, we’re working to ensure that each student possesses not just a transcript of

grades but a comprehensive profile demonstrating growth across all dimensions of meaningful

learning. This approach transforms assessment from a measurement tool into a powerful driver

of educational excellence and personal development.

The true power of assessment lies not in its ability to judge but in its capacity to illuminate paths

for growth—for students, teachers, and our educational system as a whole.

Q4. How do you leverage global best practices across GIIS campuses to raise quality? How important and helpful do you think this sharing of best practices is for improvement?

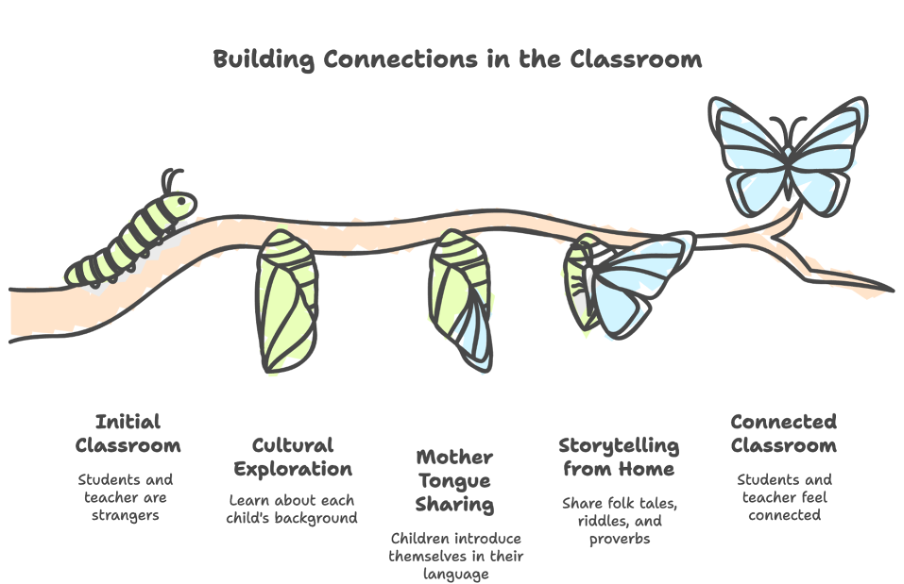

- Student Exchange Programmes:The Programme offers transformative cultural immersion experiences through a variety of pathways in-person and virtual. These pathways are designed specifically to develop global competencies, language skills, and cross-cultural understanding while experiencing diverse educational approaches. The programme structure includes authentic cultural engagement and meaningful collaborative projects. While this programme is intended to focus on cross-cultural experiences, it inadvertently helps us share best practices of pedagogies, processes and attitudes across students and teachers.

- Annual Leadership Summits (Global and Local):

through collaboration and knowledge exchange. The summit pivots on two core objectives:

(a). sharing effective practices across educational contexts and

(b). developing innovations in pedagogical approaches.

Participants attend workshops, problem-solving sessions, and presentations featuring practical teaching, leadership strategies and technological innovations. Through regional and global meetings, the summit creates opportunities for educators to connect, exchange ideas, and implement improvements to benefit students.

- Professional Learning Communities: We have established cross-campus PLCs that bring together subject specialists and pedagogical experts to share innovative teaching approaches, assessment strategies, and curriculum enhancements. These collaborative groups meet regularly online and produce resource banks and teaching toolkits that are implemented across all campuses.

- Digital Repository of Excellence: Our proprietary online platform houses exemplary lesson plans, assessment tools, and teaching resources curated from all our campuses. Teachers can access, adapt, and implement these proven effective practices in their own classrooms, ensuring quality teaching across diverse geographical contexts.

The Critical Importance of Sharing Best Practices

The sharing of best practices across our network is not merely helpful—it is fundamental to our educational mission for several compelling reasons:

Quality Standardisation with Contextual Adaptation:By identifying and disseminating what works best, we establish consistent quality benchmarks across all our campuses while allowing for necessary cultural and contextual adaptations. This ensures that students receive comparable educational experiences regardless of location, while honouring local contexts. Accelerated Innovation: When educators share successful strategies, we eliminate the need for each campus to ‘reinvent the wheel.’ This accelerates our collective growth and allows innovations to spread rapidly throughout our network, keeping our educational approach current and effective.Evidence-Based Improvement:Our approach to sharing best practices is deeply evidence-based. We systematically collect data on student outcomes when implementing shared practices, allowing us to continuously refine our methods based on measurable results rather than assumptions.

Professional Growth for Educators: The cross-pollination of ideas creates rich professional development opportunities for our teachers. When educators engage with diverse approaches from colleagues worldwide, they expand their pedagogical repertoire and develop greater adaptability and creativity in their teaching.

Resource Efficiency:Sharing best practices enables more efficient use of our resources. Successful initiatives developed at one campus can be scaled across others without duplicating development efforts, allowing us to invest more in implementation and refinement.

The true power of our global network lies in this systematic sharing of excellence. When a mathematics teacher in Singapore discovers an effective approach to teaching complex concepts, a teacher in Japan can immediately benefit from this insight. When our UAE campus develops an innovative wellbeing programme that demonstrates positive outcomes, schools in India can adapt and implement it within weeks.

This continuous cycle of sharing, adapting, implementing, and refining best practices creates an educational ecosystem that is simultaneously stable in its quality foundations and dynamic in its approach to innovation. It is this balance that enables us to fulfil our promise of educational excellence to every student in every location.

Q5. If you were to talk about three common mistakes that every school leader should be cautious of, what would these be?

- Academic Excellence

- Administrative Efficiency

- Health And Safety Vigilance

- Fiscal Sustainability, And

- Communication Transparency

With such expansive responsibilities, even experienced leaders can fall into common traps that undermine their effectiveness and school culture.

In my personal opinion, I’ve observed three critical mistakes that school leaders should vigilantly guard against:Prioritising People Dependency Over Process Development

Many school leaders build operations around specific trusted individuals rather than robust systems. When these key people are absent or depart, critical functions falter. This mistake often manifests as:

- Institutional knowledge residing in individuals rather than documentation

- Inconsistent handling of recurring situations

- Vulnerability during staff transitions

- Resistance to process standardisation (“we’ve always done it this way”)

Effective school leaders create systems where excellent people operate within clear processes. This means:

- Documenting standard operating procedures for critical functions

- Creating accessible policy handbooks that guide decision-making

- Establishing workflow systems that continue functioning despite personnel changes

- Building redundancy in essential operational knowledge

Some leaders misinterpret their positional authority as license to make unilateral decisions. This top-down approach alienates faculty, stifles innovation, and creates compliance without commitment. Telling signs of such leadership include:

- Limited faculty input on significant decisions

- Micromanagement of department activities

- Low psychological safety for expressing concerns

- Resistance to feedback from team members

The accountability pressure on principals can create fear-based leadership. Additionally, the traditional hierarchical structure of schools can reinforce authoritarian tendencies.

School excellence emerges from collaborative leadership where:- Decision-making processes include those affected by the outcomes

- Faculty expertise drives pedagogical innovation

- Leadership focuses on asking powerful questions rather than providing all answers

- Authority is used to empower others, not control them

- Regular feedback mechanisms allow for course correction

School leaders often assume their communications are understood as intended. This creates

execution gaps, misaligned expectations, and unnecessary conflicts. This manifests as vague

directional guidance without specific expectations, inconsistent messaging across different

stakeholder groups, assuming single communications create lasting understanding and

neglecting to confirm comprehension of critical messages.

The volume of daily communications and diverse stakeholder needs make precision difficult.

Furthermore, leaders often have deeper contextual understanding than those receiving their

communications.

Effective school leaders must recognise that communication requires precision and intentionality,

not just volume. They should craft messages with careful consideration of potential

interpretations, actively verify understanding through systematic feedback mechanisms, and

reinforce key information across multiple channels to ensure retention. School leaders must strive

to establish communication systems that maintain consistency regardless of the messenger,

while skilfully adapting their communication style to meet the unique needs of different

stakeholder groups.

By treating communication as a strategic skill rather than an afterthought, one can prevent

misalignments, reduce conflict, and create the shared understanding necessary for school-wide

excellence.

Leadership excellence requires continuous self-examination. The best school leaders recognize

these pitfalls not as failures but as growth opportunities—moments to shift from reactive

management to strategic leadership.

The most admirable educational leader is one who establishes clear processes while valuing

people, exercises authority while promoting collaboration, and communicates with both clarity

and empathy. Such leaders, as I often tell principals, “lead from the front during challenges, walk

alongside during implementation, and celebrate from the background during success.”

Enjoyed the read? Spread the word

Interested in being featured in our newsletter?

Feature Articles

Join Our Newsletter

Your monthly dose of education insights and innovations delivered to your inbox!

powered by Advanced iFrame