Edition 14 | February 2026

Edu- Praxis

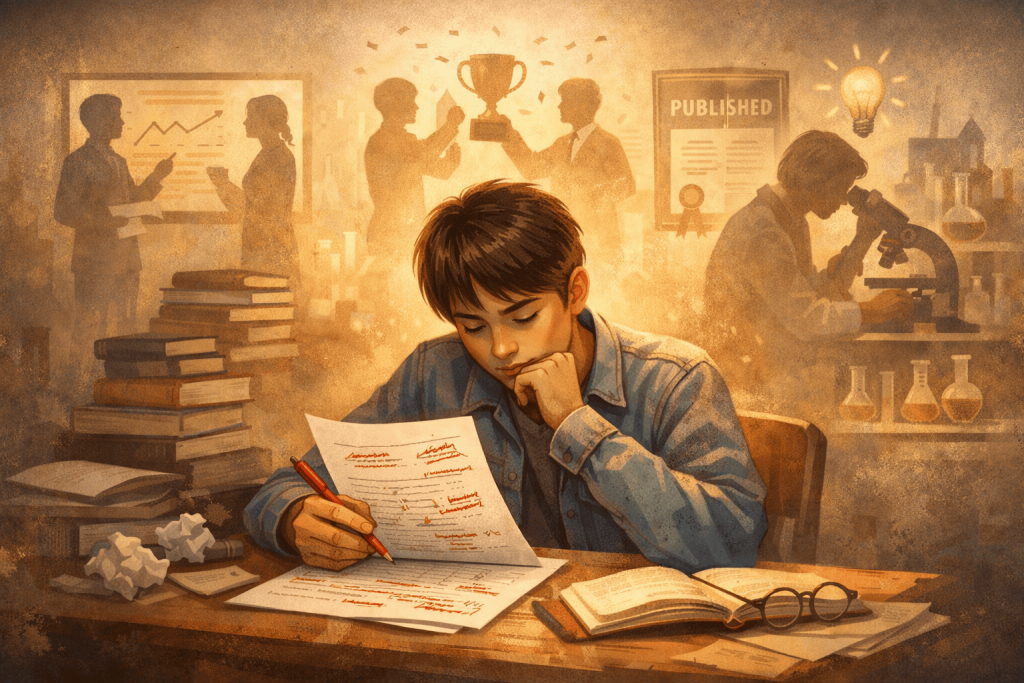

The Importance of Failing

Table of Contents:

The Study

A research study analysing early-career grant applications found that scientists who narrowly missed funding were more likely to produce high-impact research later in their careers compared to those who narrowly secured funding, suggesting that early setbacks can strengthen long-term success for those who persist.

Paper: ‘Early-career setback and future career impact’

Wang, Dashun; Benjamin F. Jones; and colleagues (2019)

Published in: Nature Communications

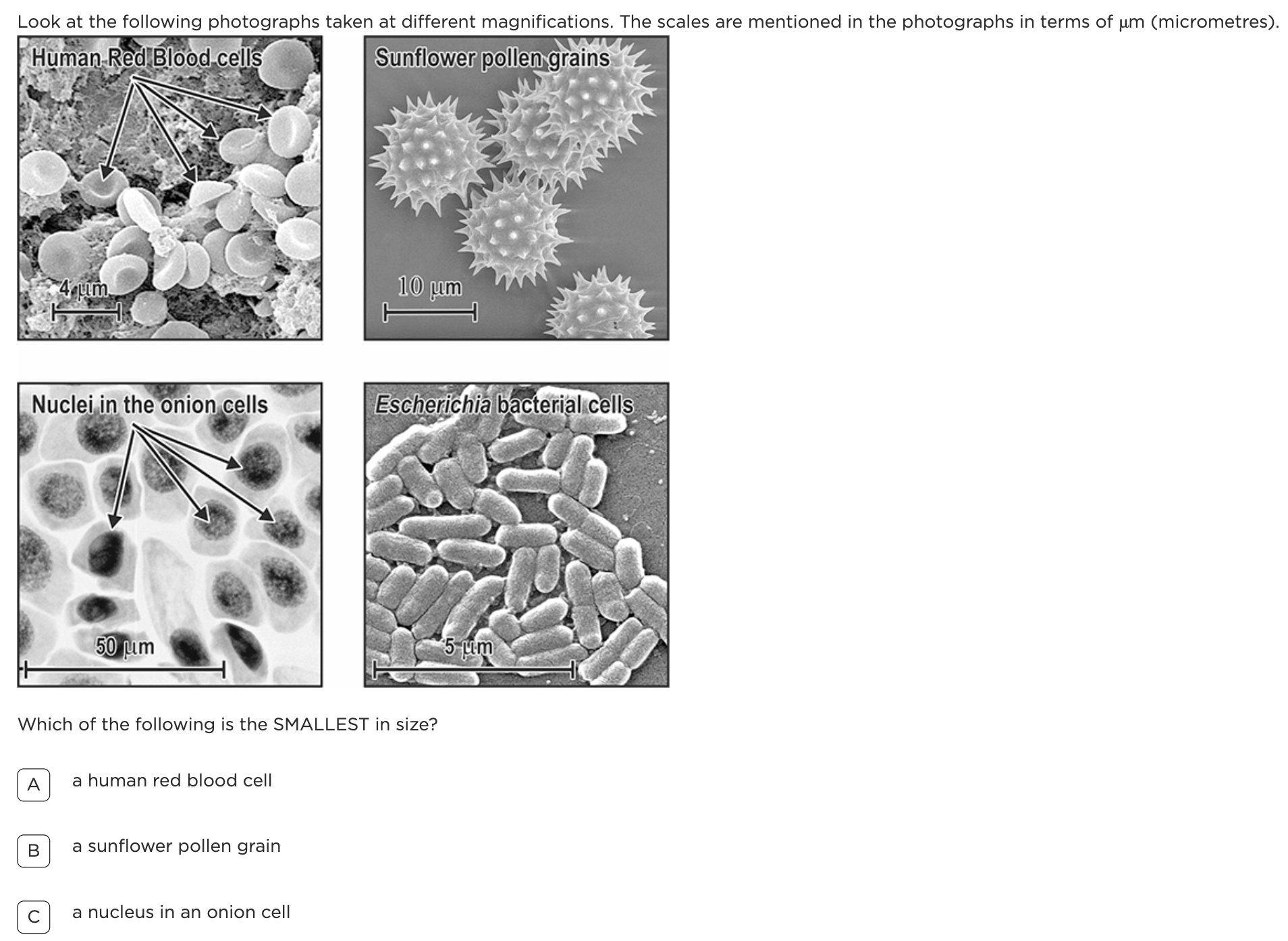

What the Study Investigated

Researchers analysed thousands of early-career scientists who applied for competitive research grants.

They compared two groups:

Scientists who just missed receiving a grant (near-miss group)

Scientists who just secured funding (near-win group)

Key Findings from the Study

Some near-miss scientists left research careers early.

However, those who remained:

Produced higher-impact research papers

Were more likely to publish highly cited (‘hit’) papers

Showed stronger long-term research influence

This is the direct evidence behind the claim that early setbacks may strengthen long-term achievement for those who persist.

The study does not claim failure automatically leads to success.

It shows:

Many near-miss individuals leave the field

But among those who stay, performance tends to be stronger

The researchers of this paper opened with the brilliant quote by Nobel Prize winner Robert Lefkowitz who said, “Science is 99% failure, and that’s an optimistic view.” So, as well as being somewhat inevitable, is failure also essential?

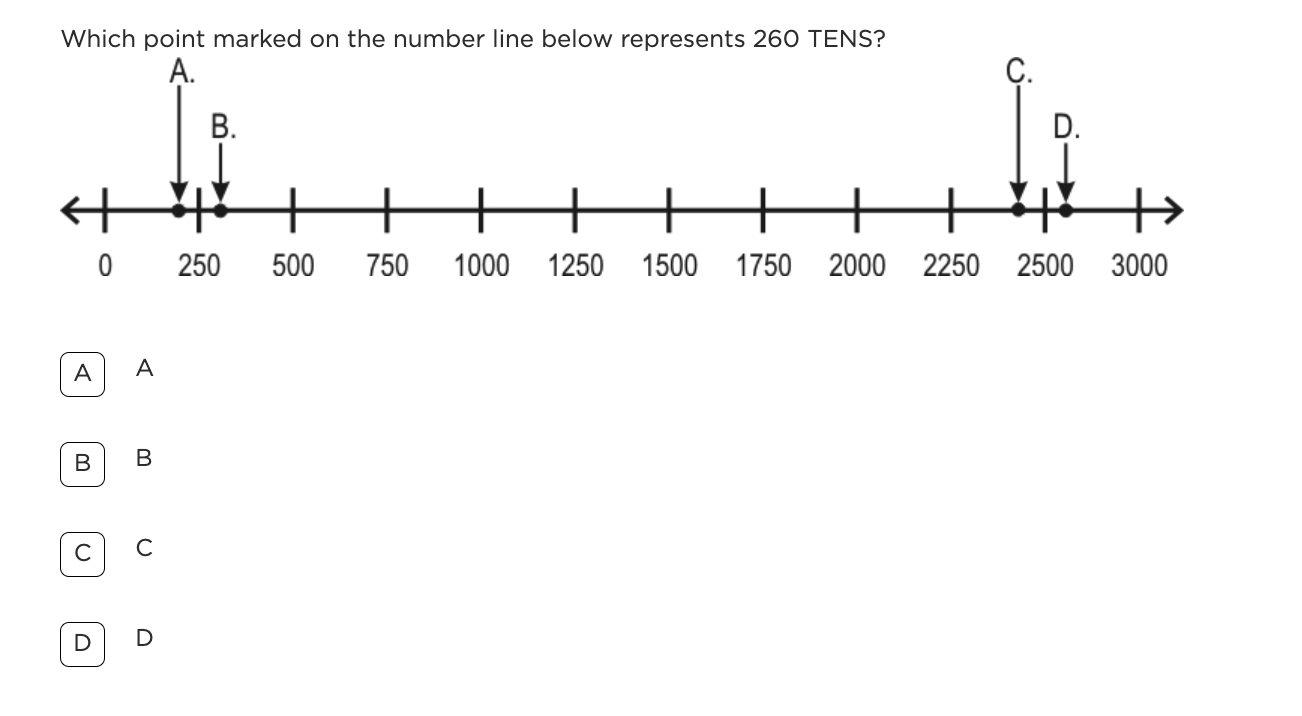

To test this, researchers from universities in China and America tracked early career scientists applying for national grants. They compared those who had failed to win a grant by a small margin, labelled as ‘near-misses’, with those who had just obtained the required threshold, labelled as ‘near wins’.

The Main Findings

Some early career scientists who experienced a ‘near-miss’ were highly demotivated and this led them to stop applying for research grants again.

Those who experienced a ‘near-miss’ early in their career had a similar number of research papers published over the next ten years as those who experienced a ‘near win’ at the beginning of their career.

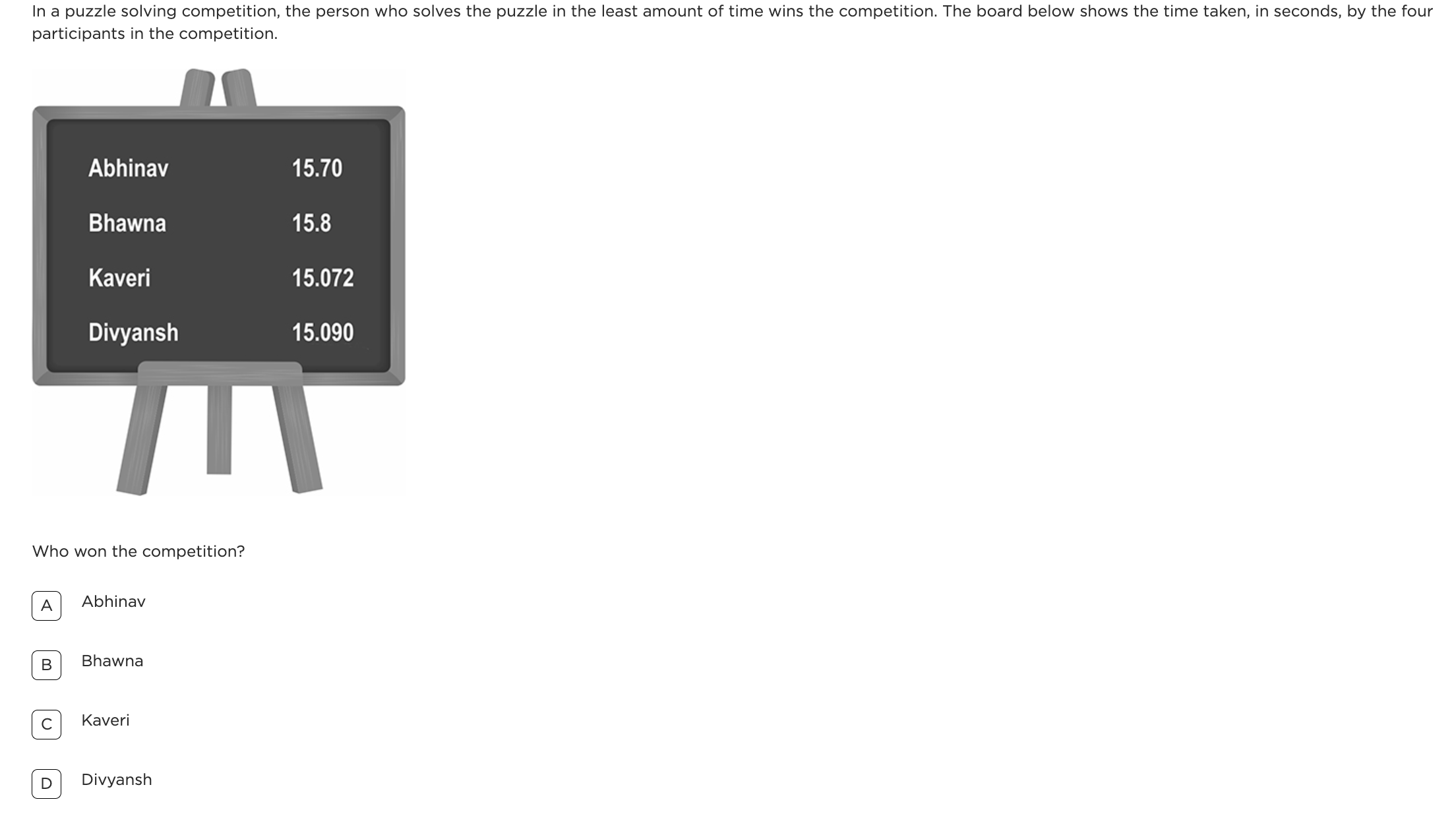

When looking at who had published a ‘hit’ paper in the subsequent five years, defined as being in the top 5% of cited papers, the ‘near-miss’ scientists were over 20% more likely to have published a ‘hit’ paper compared to the ‘near winners’.

The researchers also found that the ‘near-misses’ were more likely to have had their work cited by other scientists and there was more potential to have their work translated into other languages. The researchers suggest these results show that the idea that ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger’ may hold true.

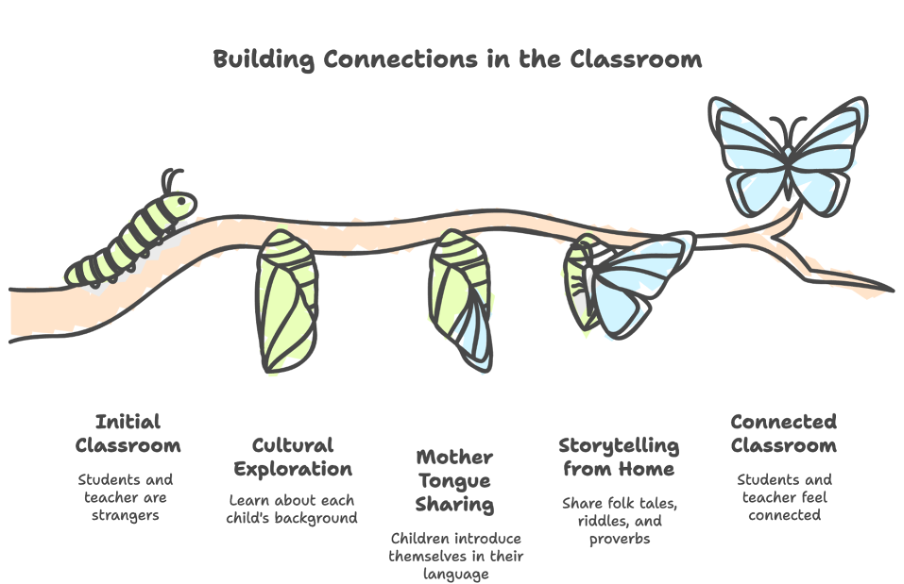

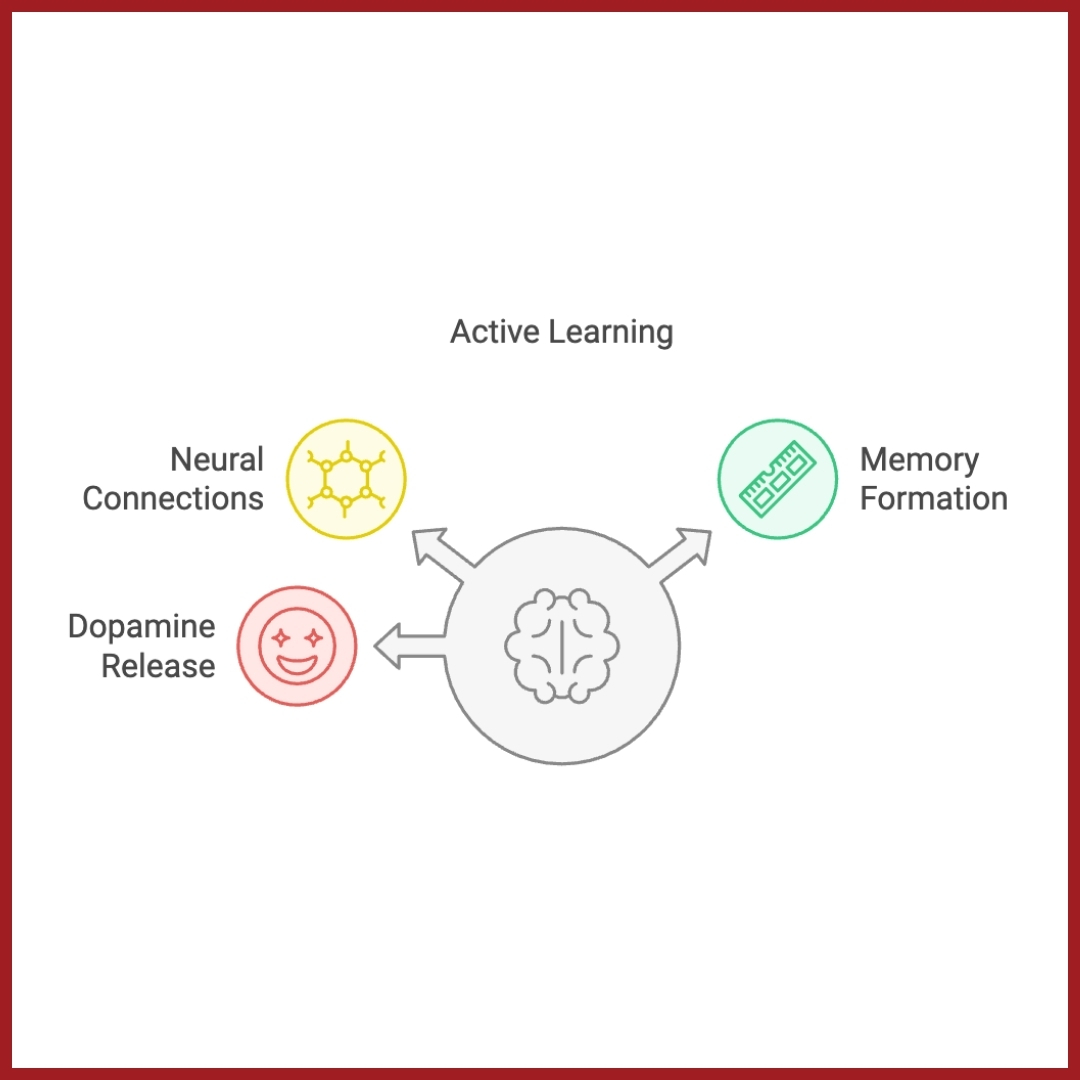

Related Research

The finding that early failures may help developing scientists is significant. Research has indicated that when students hear about scientists who have failed at some stage in their career, they feel more connected to them. This has led to higher achievement in science examinations, particularly among students who had previously been struggling. One explanation is that recognising failure as part of success may help develop a growth mindset, which supports resilience, self-esteem and enjoyment in learning.

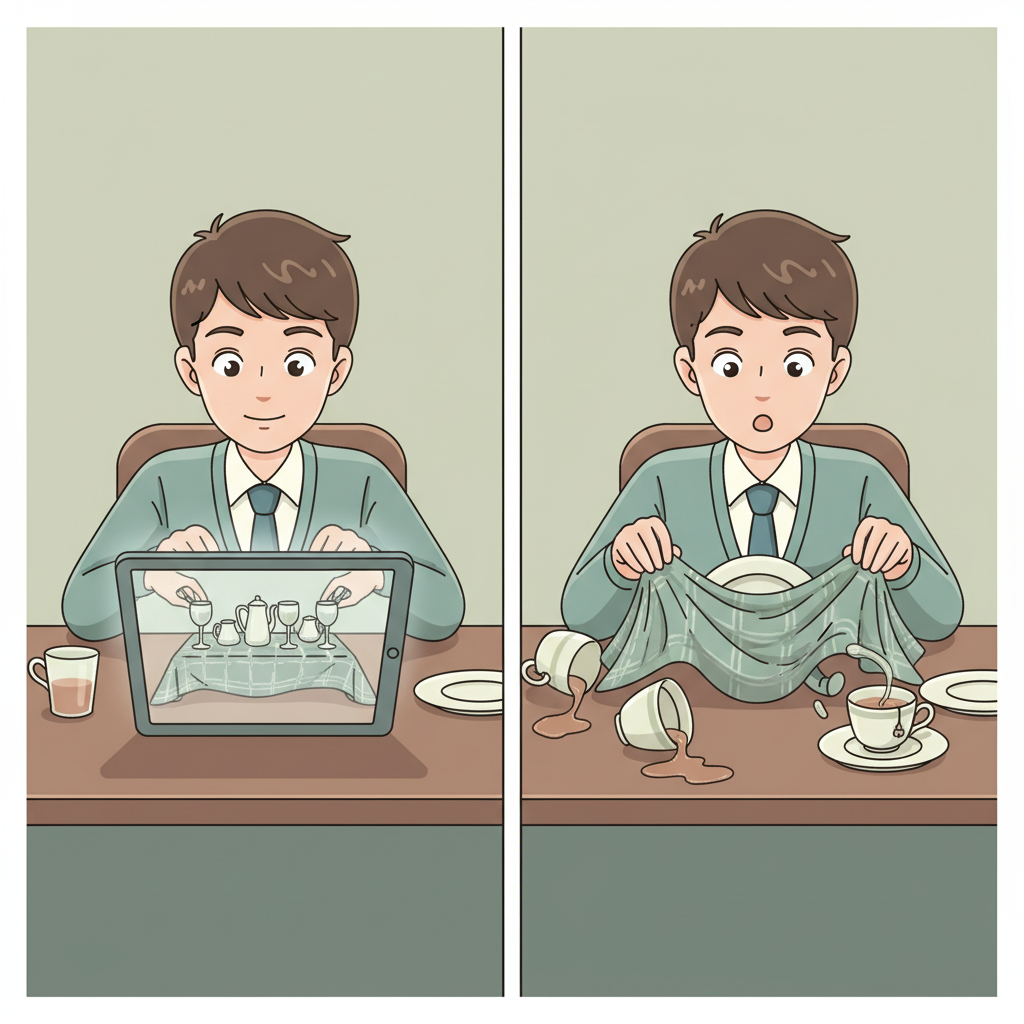

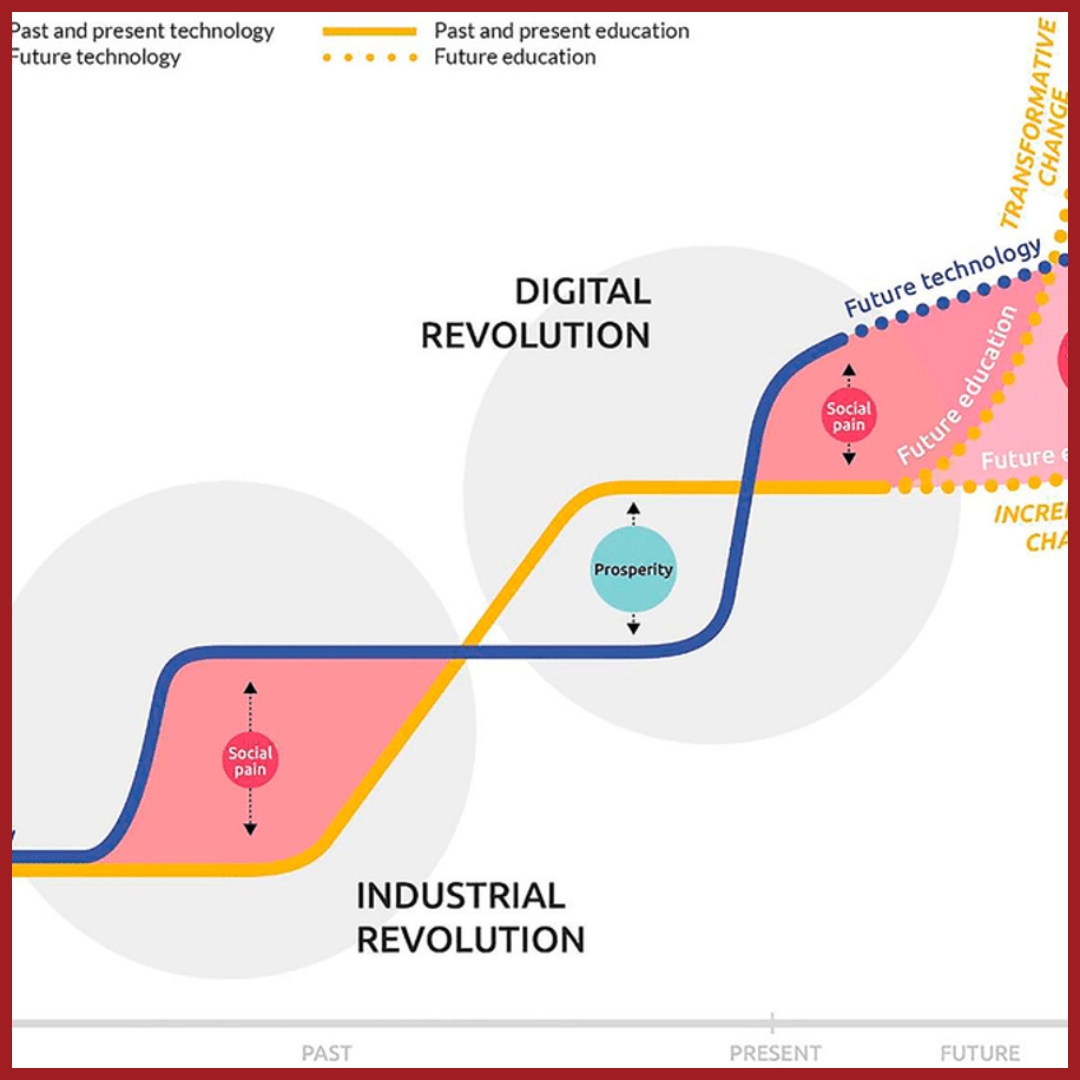

Research on the effect of success and failure has produced mixed findings. Some studies have shown a Matthew Effect, where early success can fuel future success through increased recognition, confidence, motivation and access to resources. Other studies highlight the benefits of failure, including learning from mistakes, increased motivation, development of resilience and greater empathy.

Classroom Implications

Normalise struggle as part of mastery

Discuss examples from real-world learning journeys where improvement occurred through revision and effort. This helps students see difficulty as expected rather than discouraging.

Shift feedback from correctness to progress

Instead of saying ‘This is wrong’, focus on:

What the student understood correctly

Where thinking needs adjustment

What strategy can be tried next

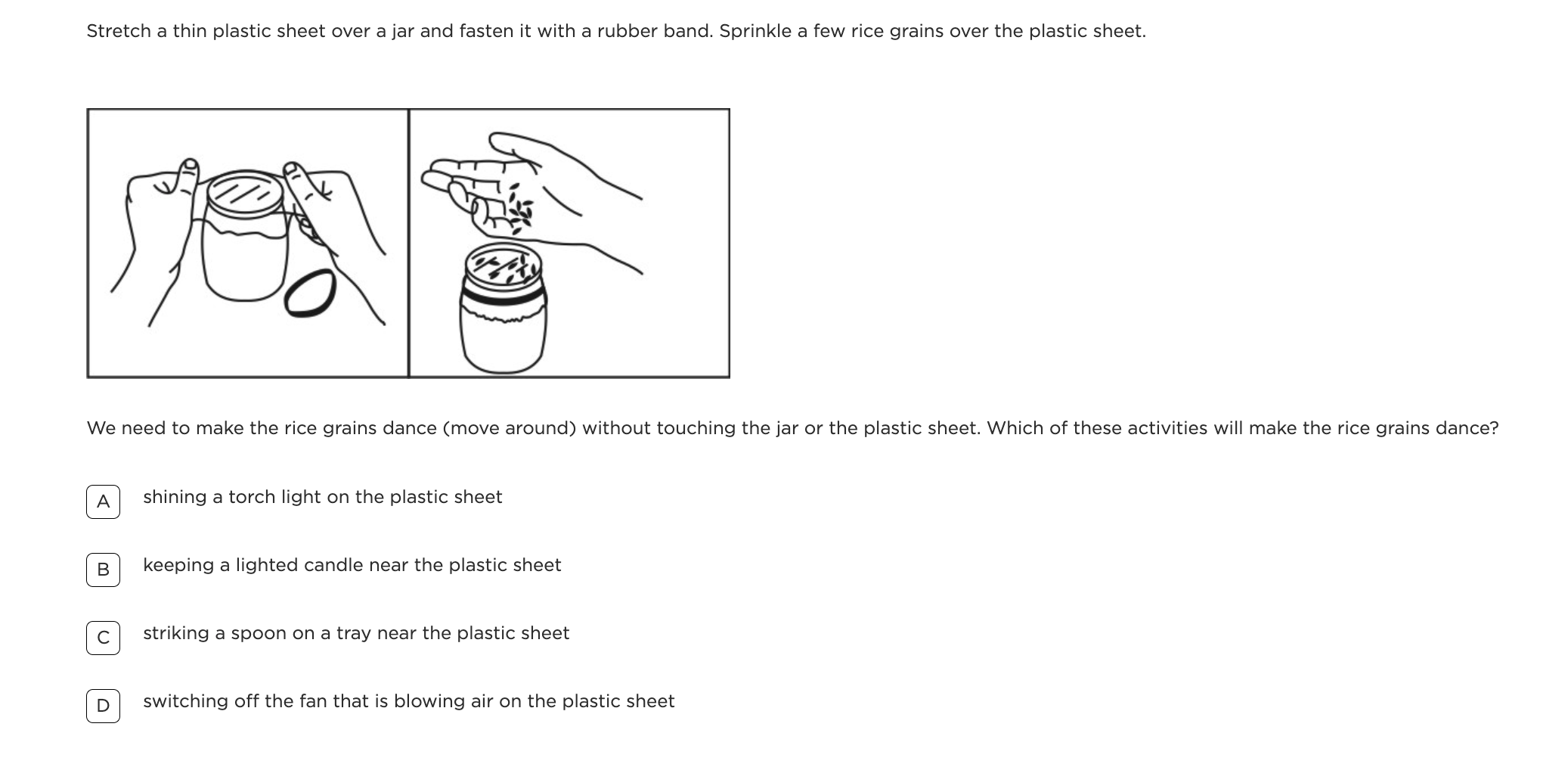

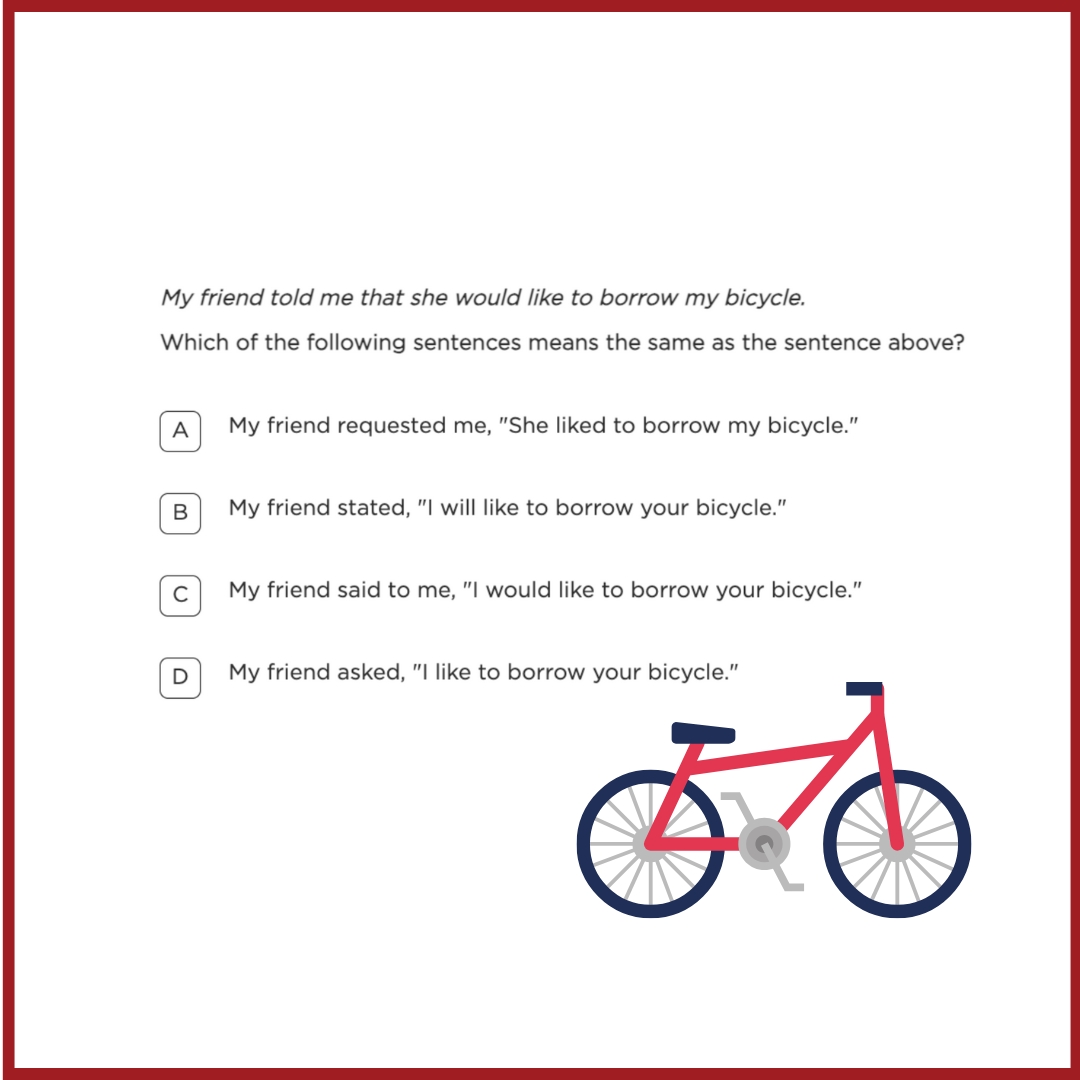

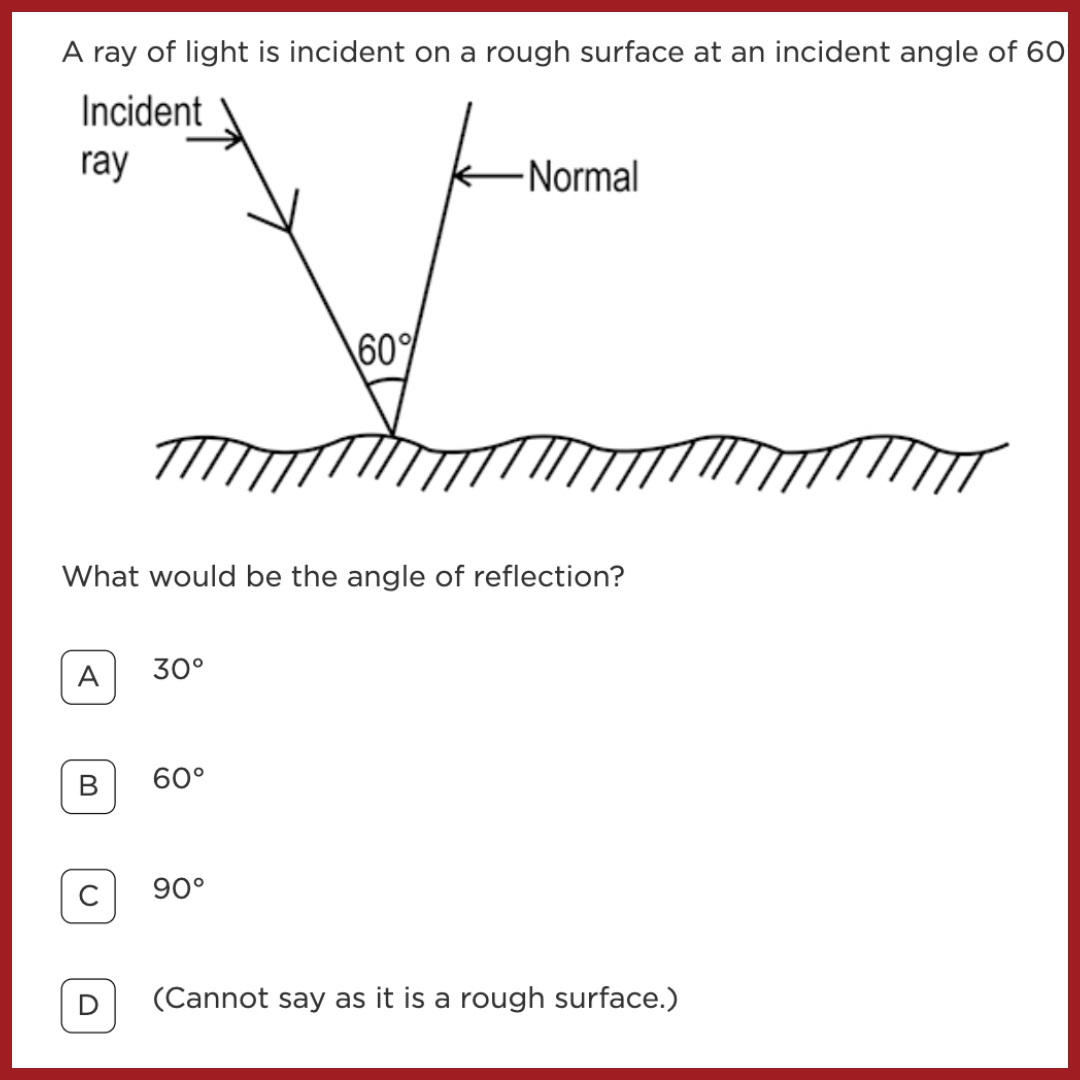

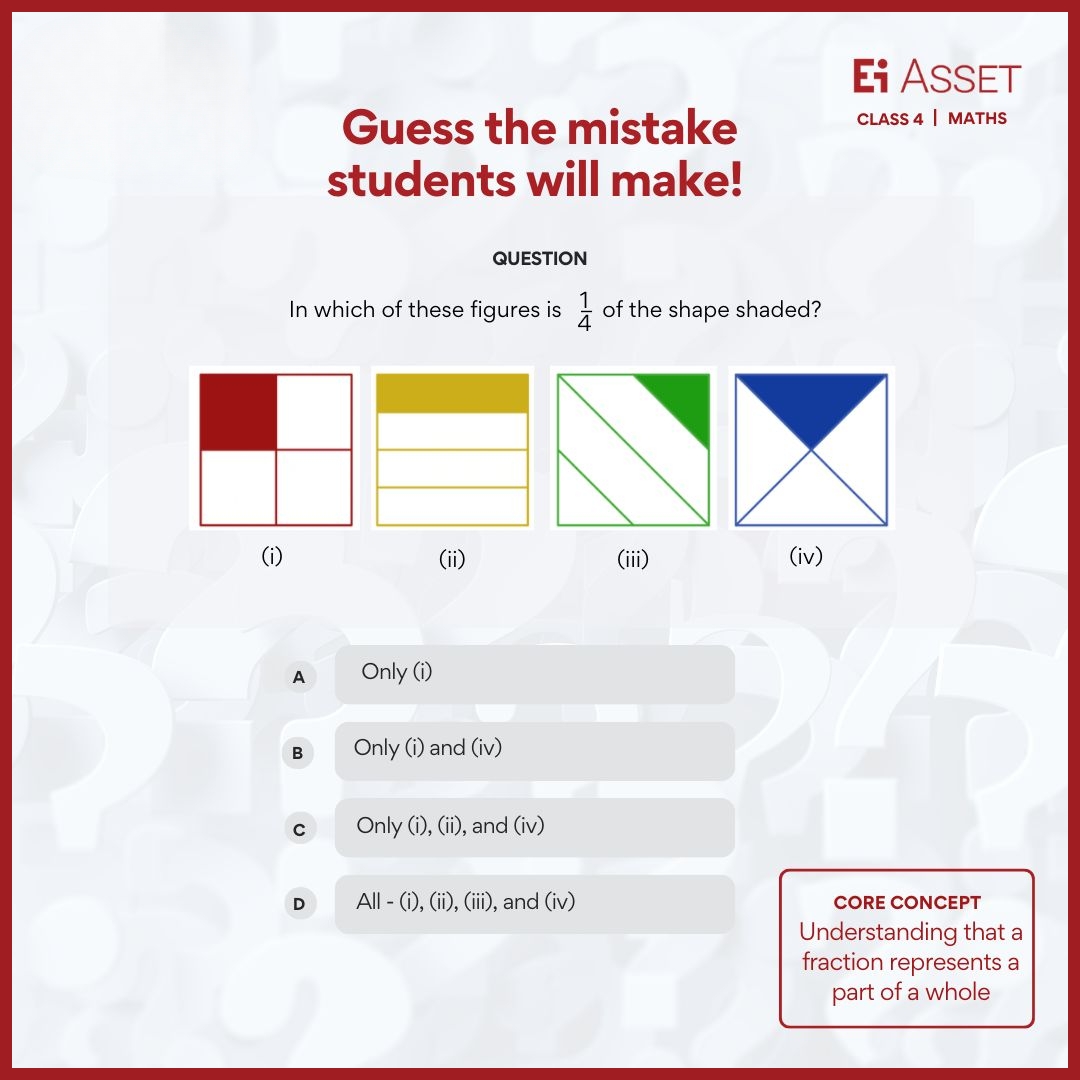

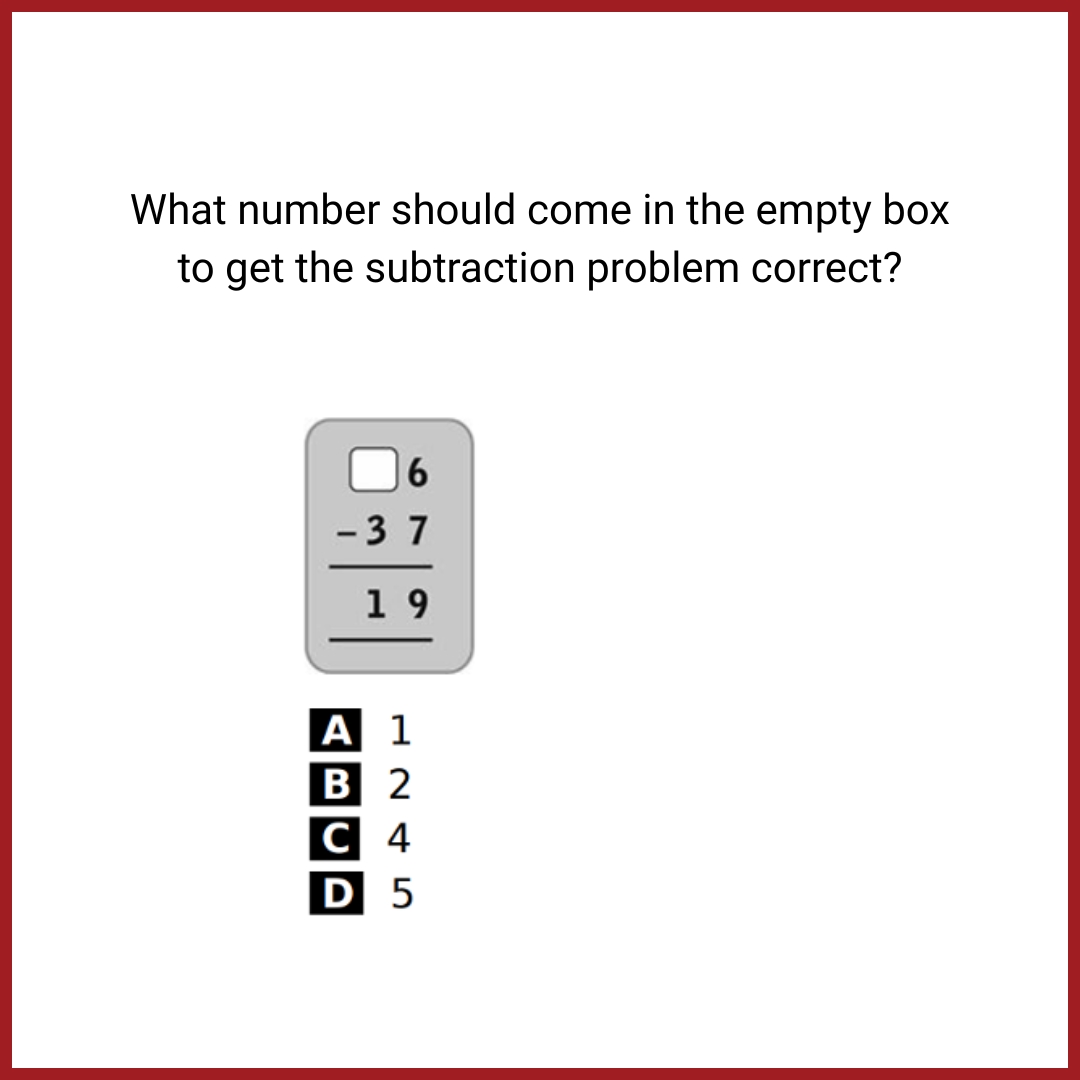

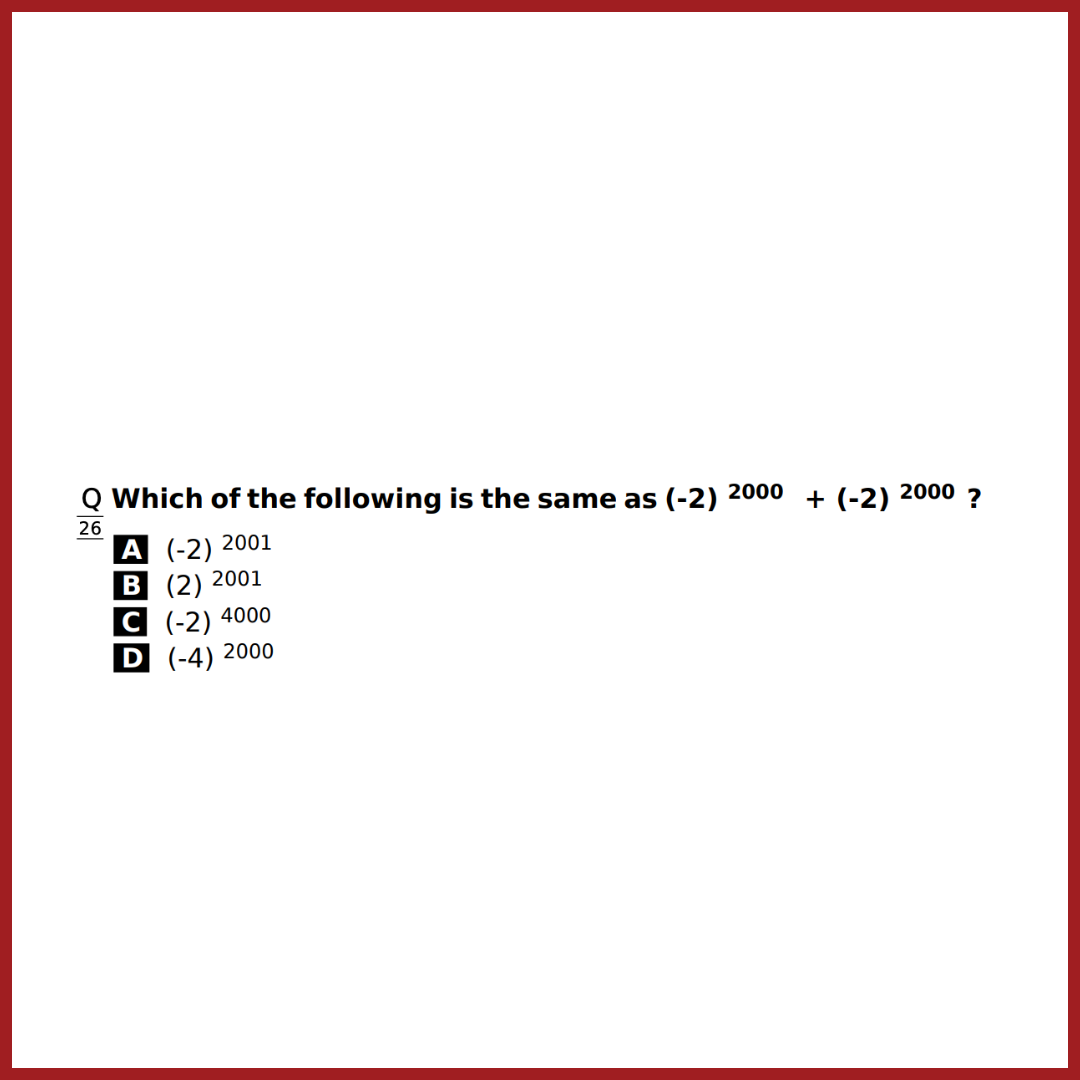

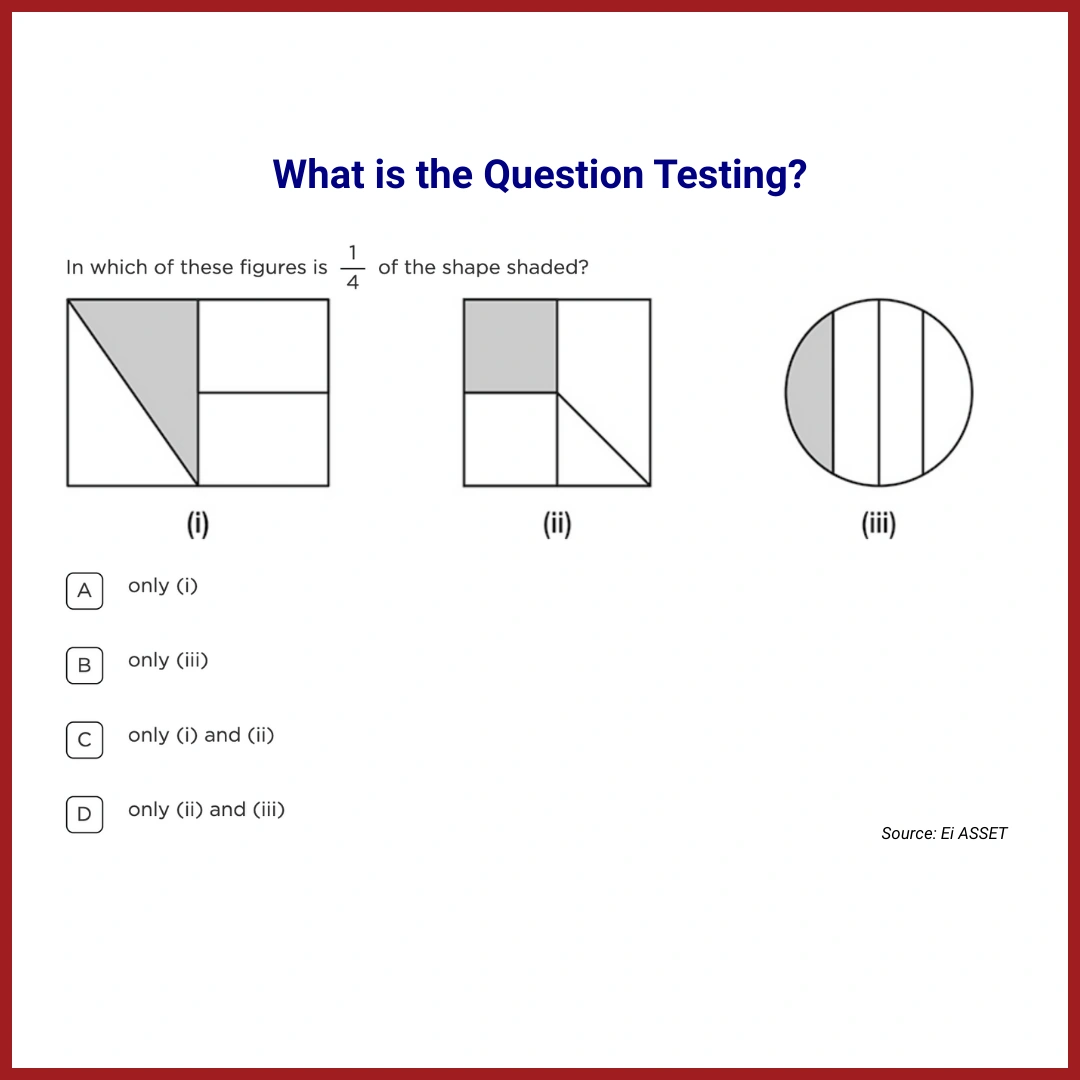

Use mistakes as teaching opportunities

Analyse common incorrect responses during class discussions. Encourage students to explain reasoning behind errors to strengthen conceptual clarity.

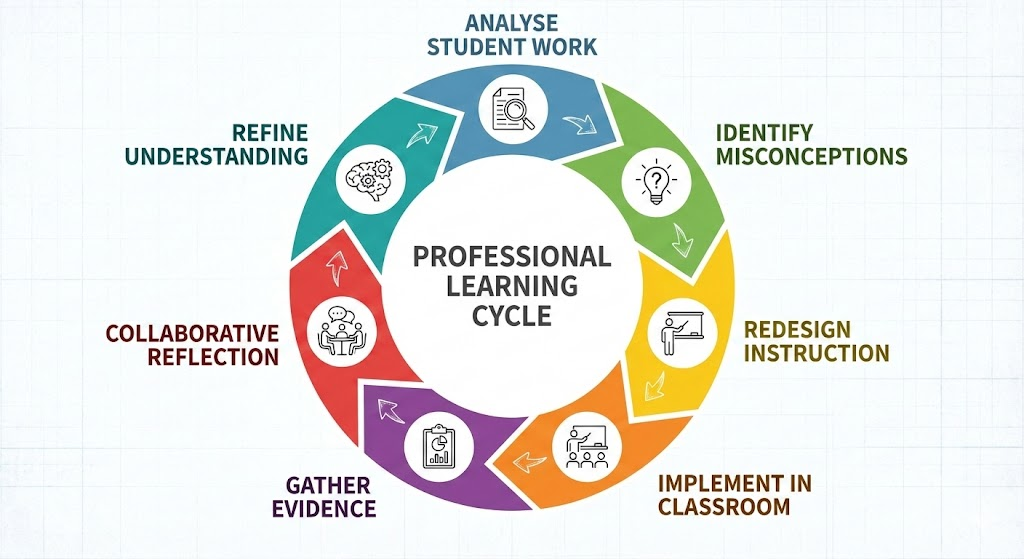

Encourage reflection after assessments

Provide structured opportunities for students to review feedback and identify improvements. Reflection strengthens metacognition and helps students take ownership of learning.

Balance challenge with support

Research shows that productive struggle occurs when tasks are demanding but achievable with guidance. Excessive difficulty without scaffolding can reduce confidence and engagement.

Try this in your class

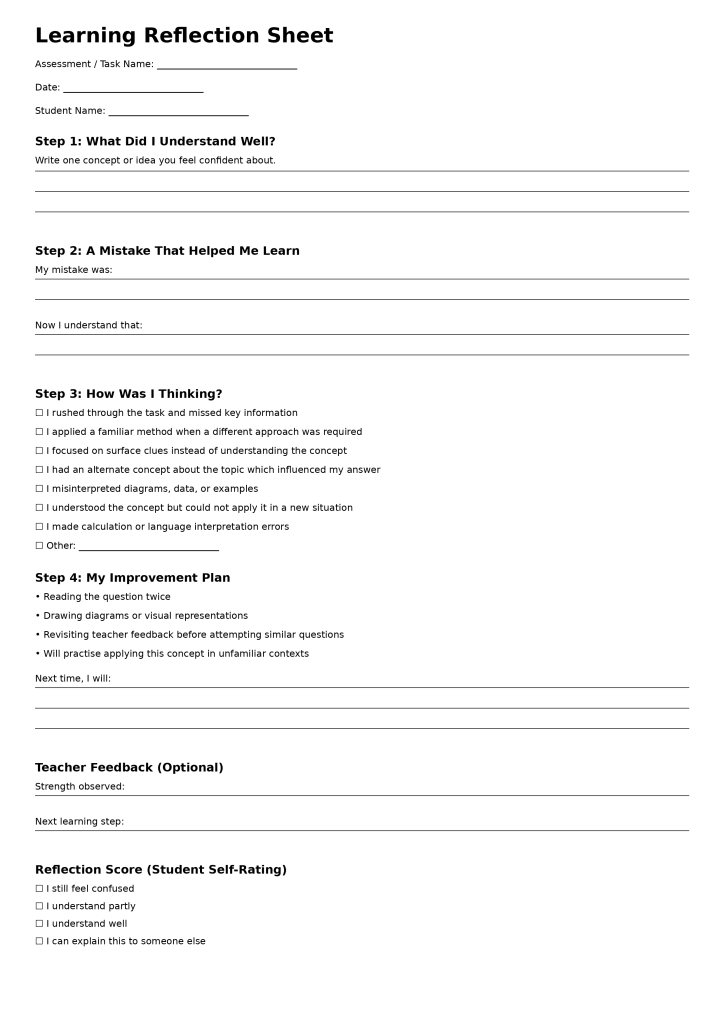

Learning Reflection Sheet: Turning Mistakes into Progress