Edition 10 | October 2025

Feature Article

Machines can think today. Can your students?

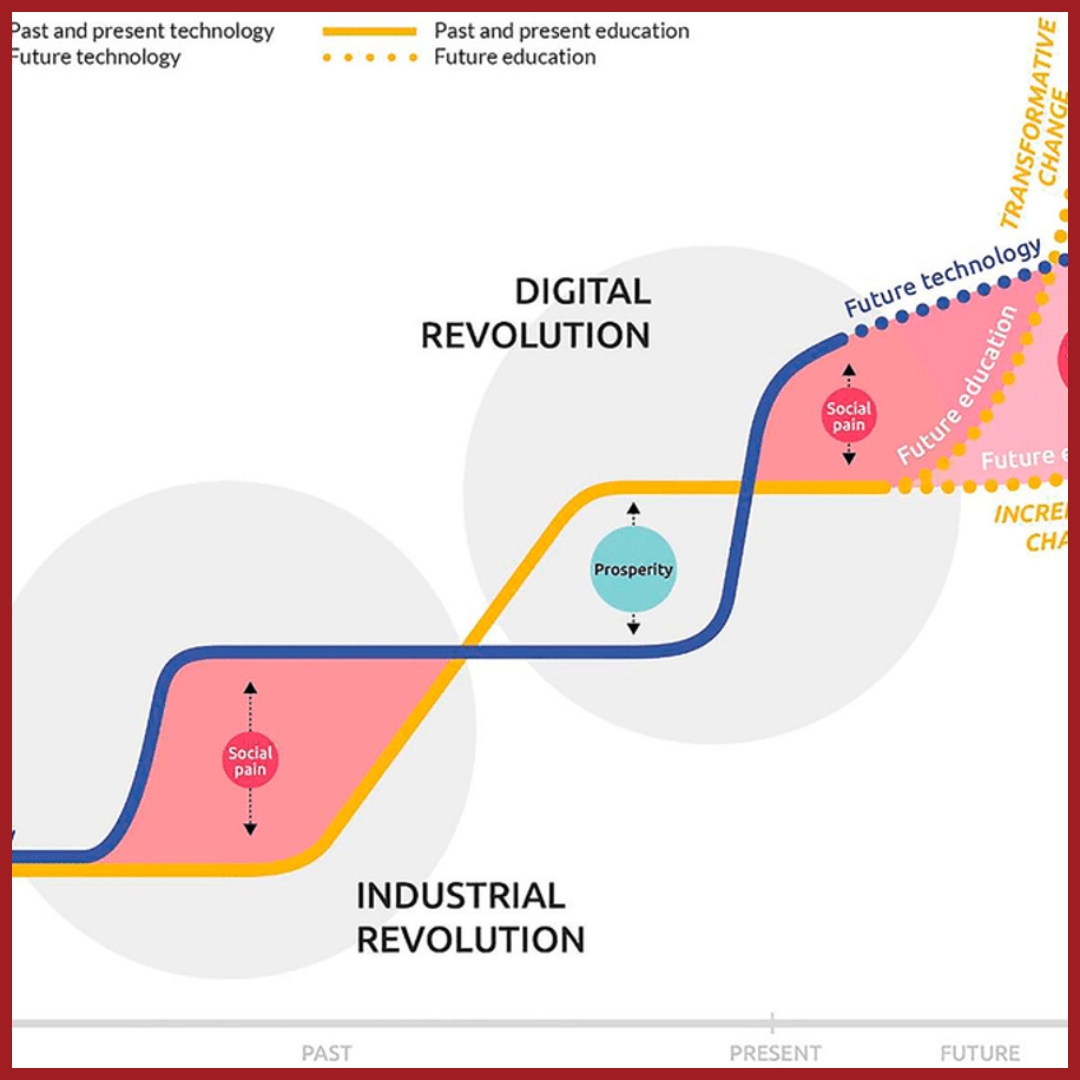

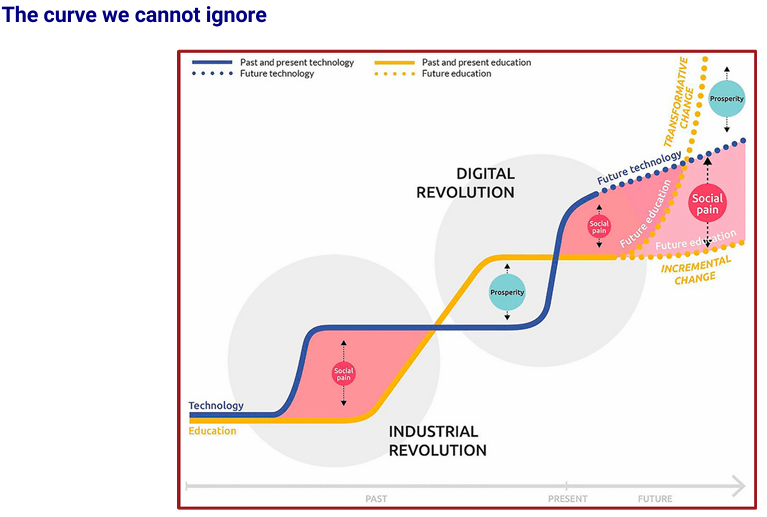

Every time technology leaps, schooling needs a strategy for the gap that follows. The present leap is different in

speed and reach. Generative and predictive systems already draft, summarise, translate, classify images, filter

information streams, and personalise interfaces. If schools continue with familiar routines, the capability gap will

widen and communities will feel the strain that the OECD graph labels as ‘social pain’ [OECD 2019].

The way out is not a shopping list of apps. The way out is a deliberate plan to cultivate thinking habits that enable students to work effectively with any system they encounter in the coming decade

The way out is not a shopping list of apps. The way out is a deliberate plan to cultivate thinking habits that enable students to work effectively with any system they encounter in the coming decade

What bold moves look like

The bold move is to teach how to think with and about technology in everyday schoolwork. Tools will rotate in

and out. Reasoning habits last. Three signals show that this is where education is headed at a system level.

First, global assessment is shifting. PISA 2025 adds Learning in the Digital World, which asks 15-year-olds to solve problems with digital tools while managing their own learning. That is a clear statement that ‘thinking with technology’ is part of what truly educated means for this generation [PISA 2025].

Second, policy frameworks embed these habits. England made Computing statutory in 2014 from the early years, with expectations around algorithms, logical reasoning, debugging, and safe, purposeful use rather than narrow software drills [DfE 2014]. CBSE introduced Artificial Intelligence as a skill subject in 2019 and released an “Inspire” module to seed foundational exposure in lower grades. Both moves formalised habits such as data awareness, model awareness, and responsible use [CBSE 2019–ongoing].

Third, guidance on responsibility is specific and practical. The U.S. Department of Education urges schools to normalise checking, citing, and documenting AI-assisted work so that verification becomes routine, not an afterthought. UNESCO asks schools to build capacity around privacy, bias, transparency, and teacher readiness. Both sources place judgment and accountability at the centre of student work [US ED 2023; UNESCO 2023].

This survives tool change because tools will evolve, but these habits will not. A student who can frame a problem, select and justify data, test outcomes, and explain decisions will adapt confidently to any system they encounter in the future workplace.

First, global assessment is shifting. PISA 2025 adds Learning in the Digital World, which asks 15-year-olds to solve problems with digital tools while managing their own learning. That is a clear statement that ‘thinking with technology’ is part of what truly educated means for this generation [PISA 2025].

Second, policy frameworks embed these habits. England made Computing statutory in 2014 from the early years, with expectations around algorithms, logical reasoning, debugging, and safe, purposeful use rather than narrow software drills [DfE 2014]. CBSE introduced Artificial Intelligence as a skill subject in 2019 and released an “Inspire” module to seed foundational exposure in lower grades. Both moves formalised habits such as data awareness, model awareness, and responsible use [CBSE 2019–ongoing].

Third, guidance on responsibility is specific and practical. The U.S. Department of Education urges schools to normalise checking, citing, and documenting AI-assisted work so that verification becomes routine, not an afterthought. UNESCO asks schools to build capacity around privacy, bias, transparency, and teacher readiness. Both sources place judgment and accountability at the centre of student work [US ED 2023; UNESCO 2023].

This survives tool change because tools will evolve, but these habits will not. A student who can frame a problem, select and justify data, test outcomes, and explain decisions will adapt confidently to any system they encounter in the future workplace.

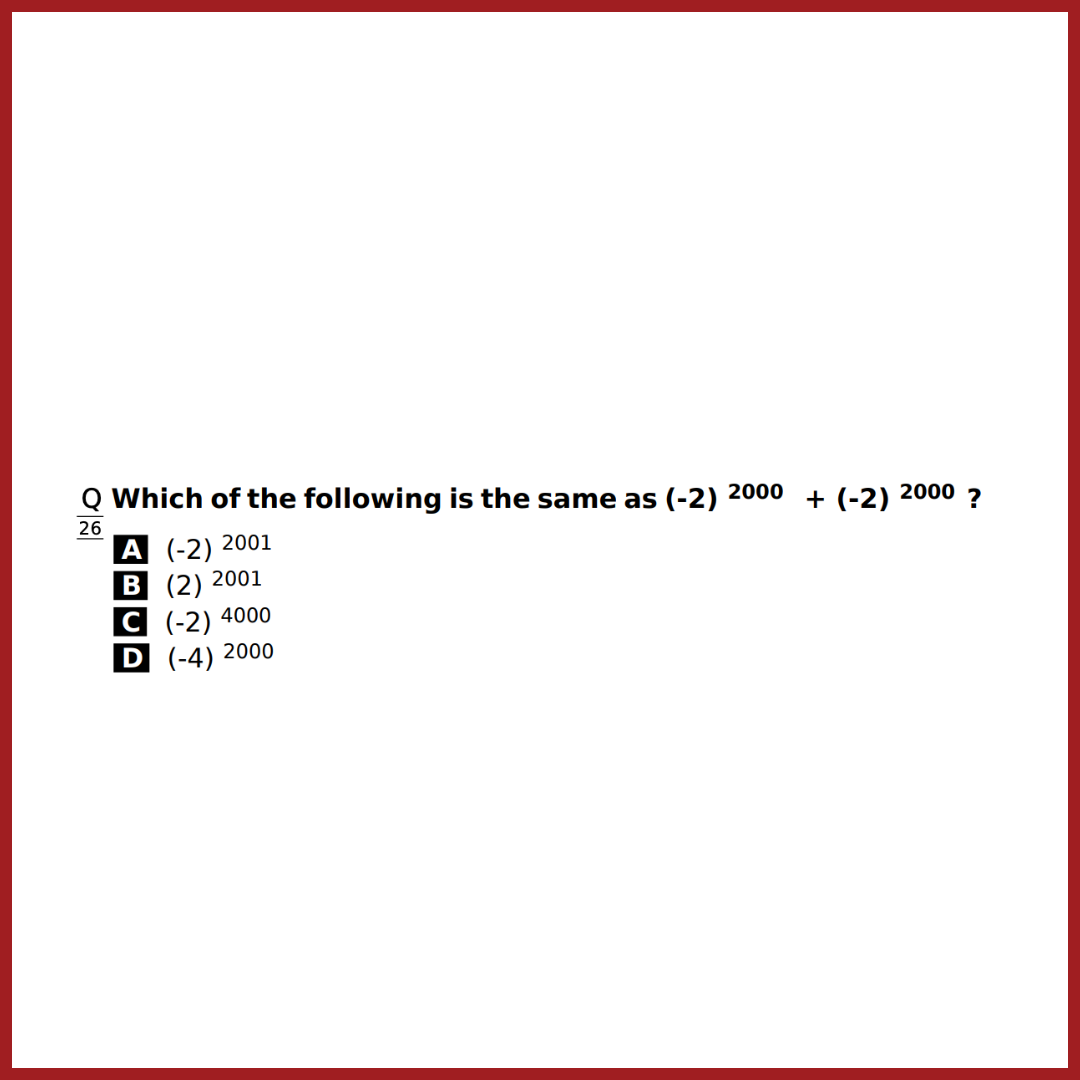

Assessing AI skills: Ei ASSET AI and Digital Thinking

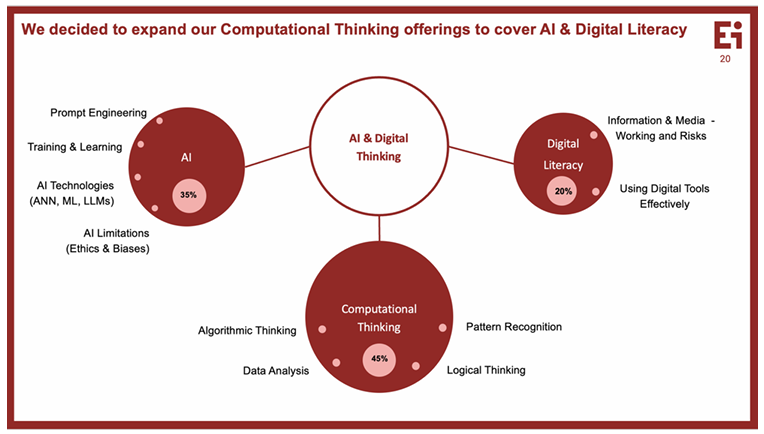

ASSET has always measured thinking with unfamiliar material. In December 2025, the AI and Digital Thinking

subject will be launched for the first time (earlier branded as Ei ASSET Computational Thinking) and will

indubitably retain that spirit. In addition to assessing Computational Thinking skills, which we at Ei treat as the

fundamental skill for a digital world, the ‘thinking backbone’ of technology, students will also be tested on their

understanding of basic AI concepts and technologies, ethical issues and biases surrounding both AI and non-AI

tools, and media and information literacy

These areas align well with international signals from PISA and policy moves in many European nations, the UAE,

and Singapore, and they give teachers a practical scope to plan around while timetables evolve.

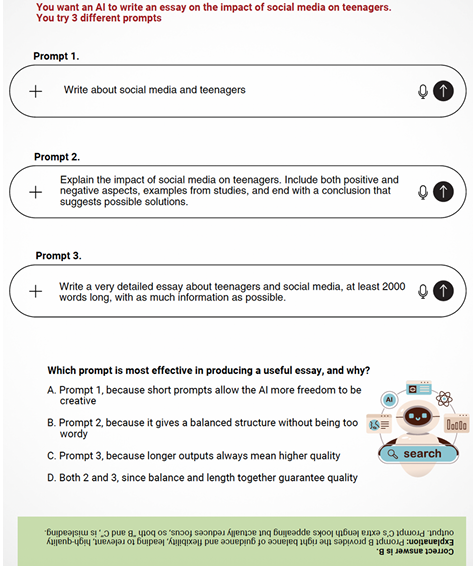

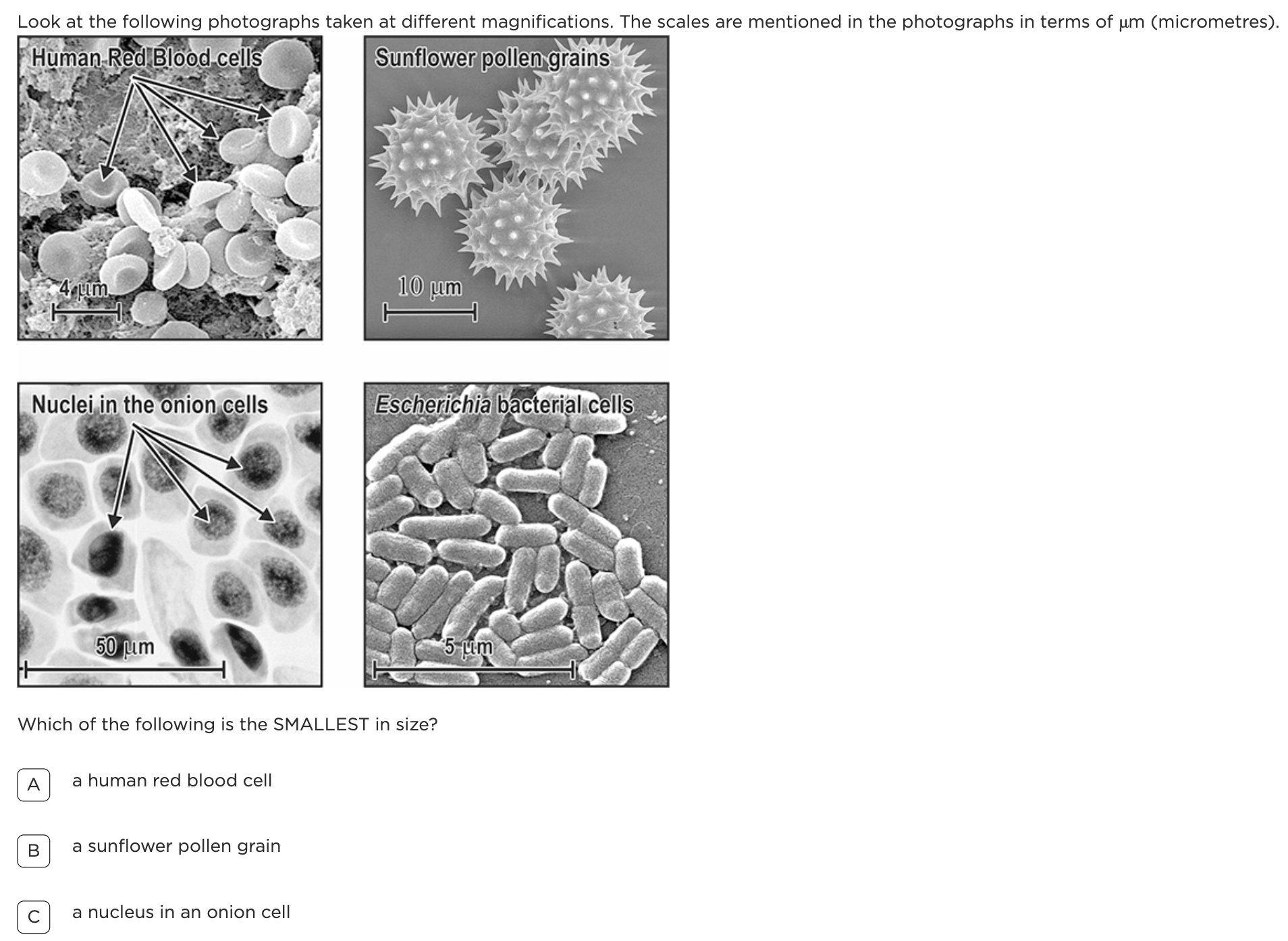

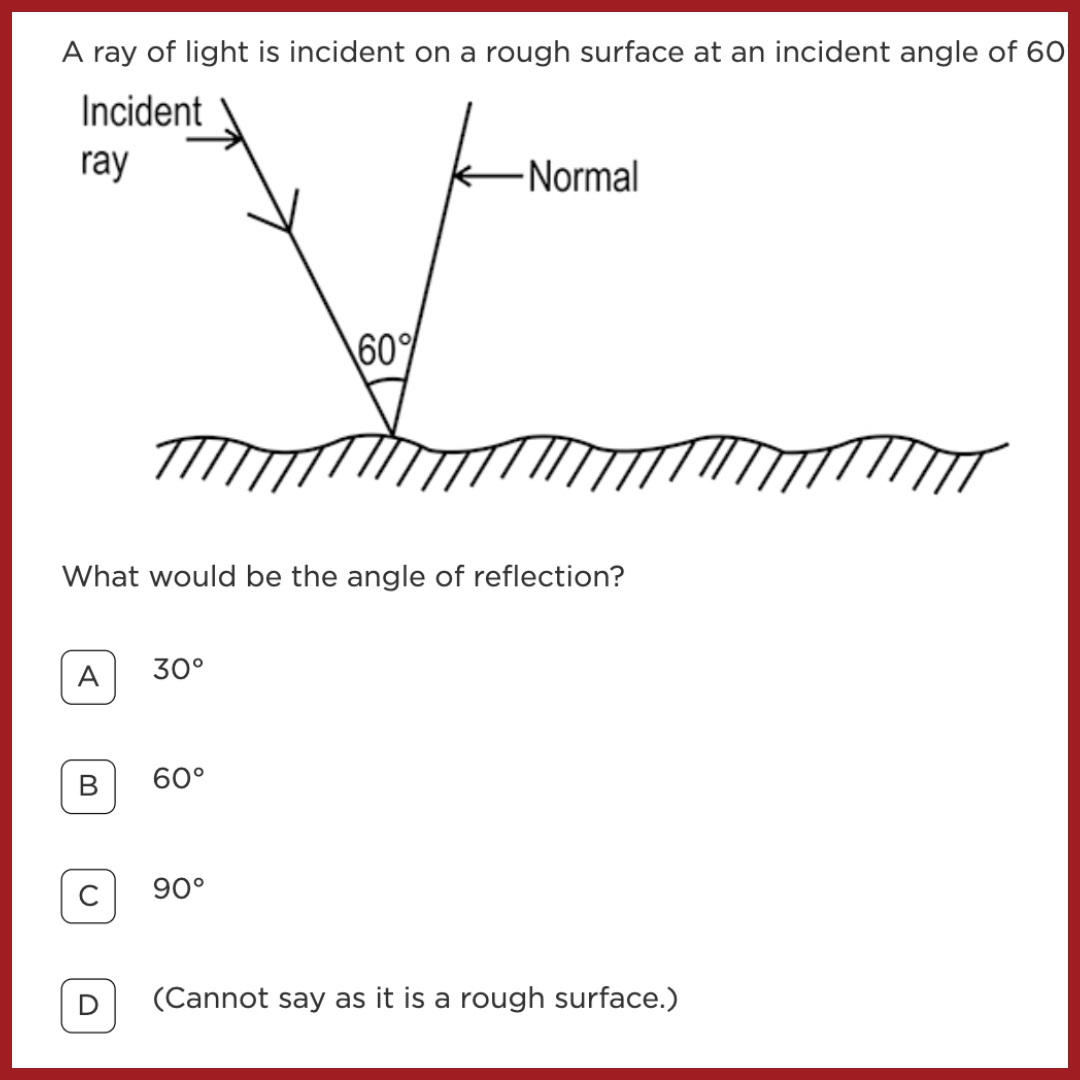

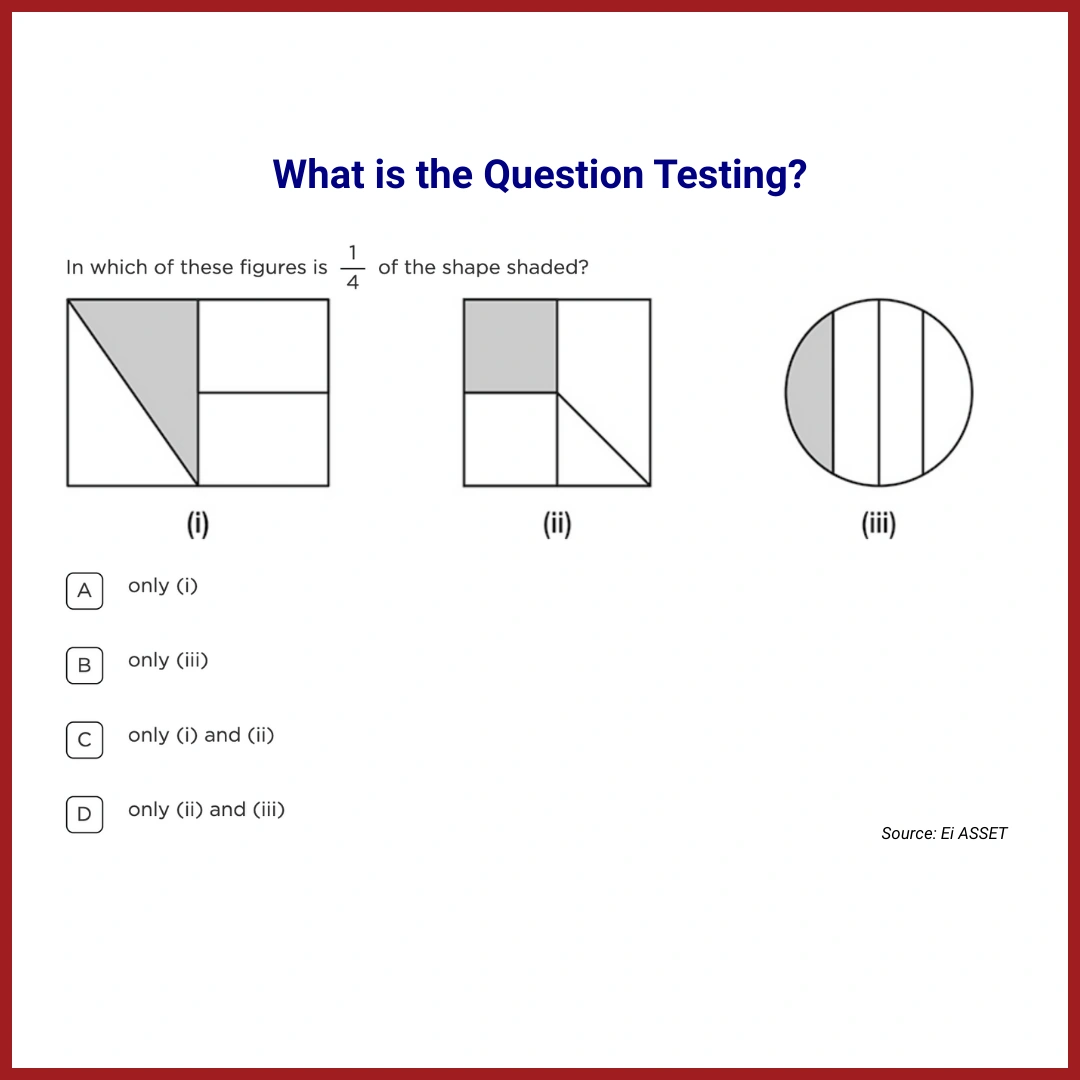

But what does it mean to assess the AI skills of students? Again, our pedagogical team has been studying this

question and defines it as ‘knowing the fundamentals of how AI models work, and how to use it effectively it to

be more productive, while also being aware of its limitations and risks’. Here are a couple of examples of the sort

of diagnostic questions that ASSET AI and Digital Thinking will test

These areas align well with international signals from PISA and policy moves in many European nations, the UAE,

and Singapore, and they give teachers a practical scope to plan around while timetables evolve.

But what does it mean to assess the AI skills of students? Again, our pedagogical team has been studying this

question and defines it as ‘knowing the fundamentals of how AI models work, and how to use it effectively it to

be more productive, while also being aware of its limitations and risks’. Here are a couple of examples of the sort

of diagnostic questions that ASSET AI and Digital Thinking will test

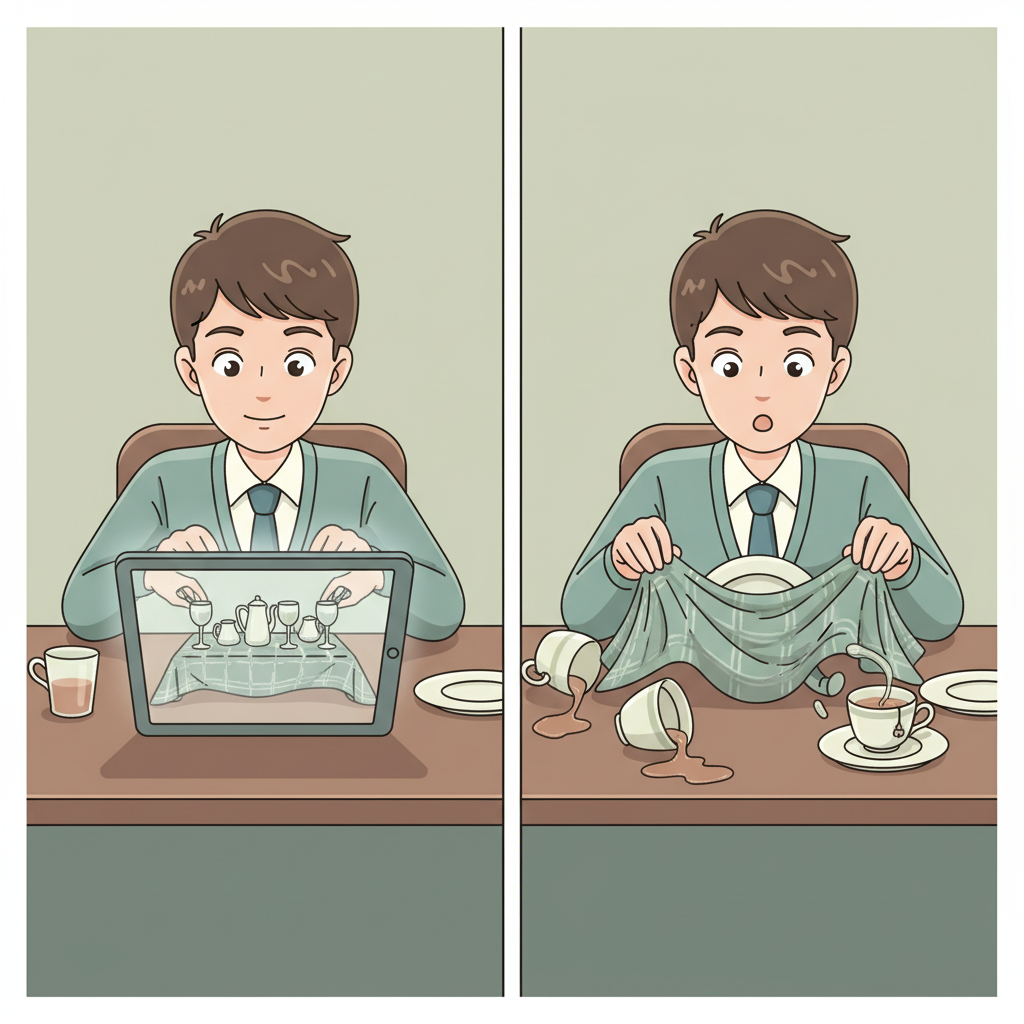

The question asks which prompt is most effective for a useful essay and why. The key is to identify B as a well scaffolded prompt that states purpose and structure usually yields a more relevant and reliable output than an open or length-maximising instruction. What the student learns is the broader skill of asking the right questions and framing it well. The student learns to plan, to make her criteria explicit, and to justify a choice using evidence about task requirements. That is verification and judgment in action via prompt engineering

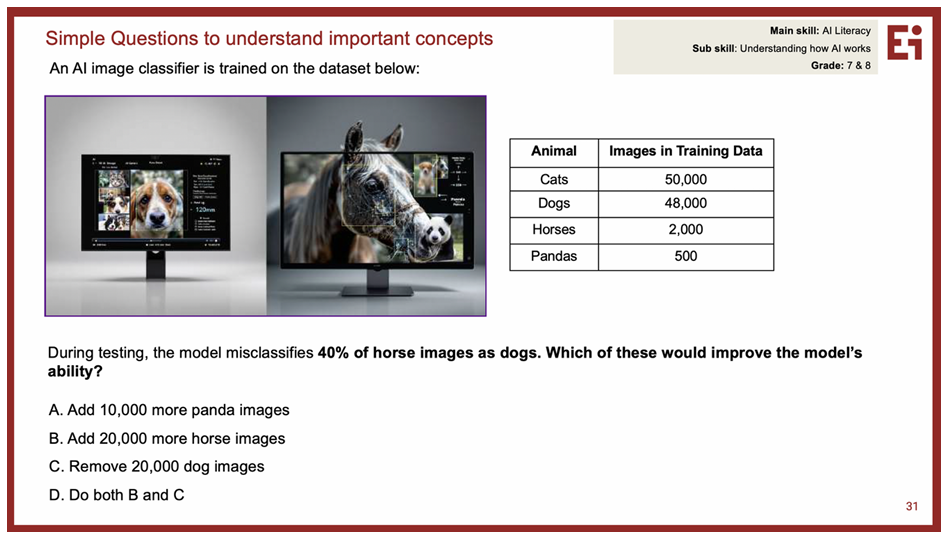

Example 2:

Skill: Training and Learning, Grades: 5-6

The question asks which change would most likely improve performance. The best action is to add more horse

images, because the error likely arises from poor representation and background cues, and the fix targets this

skewed data distribution. But we also want the child to be wary of not taking away dog images, which might

improve performance on horses but reduce performance on dogs. Again, the student is practicing model sense

and data sense: diagnose the cause, change the dataset in a way that tests the hypothesis, then evaluate the

effect

References

- OECD. Going Digital: Shaping Policies, Improving Lives (2019). Figure commonly titled “Social pain and prosperity with the industrial and digital revolutions.”

- OECD. PISA 2025: Learning in the Digital World assessment framework and overview (2023–2024 drafts).

- Department for Education, England. National Curriculum in England: Computing programmes of study, statutory from 2014.

- Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE). Circulars introducing Artificial Intelligence as a skill subject from 2019, and the “Inspire” module for lower grades.

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Teaching and Learning: Insights and Recommendations (2023).

- UNESCO. Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research (2023).

Are these principles already part of your teaching toolkit?

We’d love to hear your story!

Share how you bring these principles to life in your classroom and inspire fellow educators. Write to us at prakhar.ghildyal@ei.study and tell us about your unique teaching journey

Enjoyed the read? Spread the word

Interested in being featured in our newsletter?

Write to us here.

Feature Articles

Join Our Newsletter

Your monthly dose of education insights and innovations delivered to your inbox!

powered by Advanced iFrame