Edition 05 | May 2025

Feature Article

Introduction

One of the memories engraved in my mind is of sitting in a history class, eyes glazed, as my teacher droned on

about dates and events. The subject itself wasn’t dull; the delivery failed to spark my imagination. Everything

changed when Mr. Jha arrived the next day. Owing to some personal circumstances, my earlier teacher Ms.

Mendes had to go on an extended leave. The absence was a blessing in disguise for our class. Instead of

lectures, Mr. Jha engaged us with debates, role-plays and projects. We didn’t just learn about the past; we

experienced it, and my love for non-fiction was born. Today, as I interact with hundreds of educators, I aim to recreate that same energy.

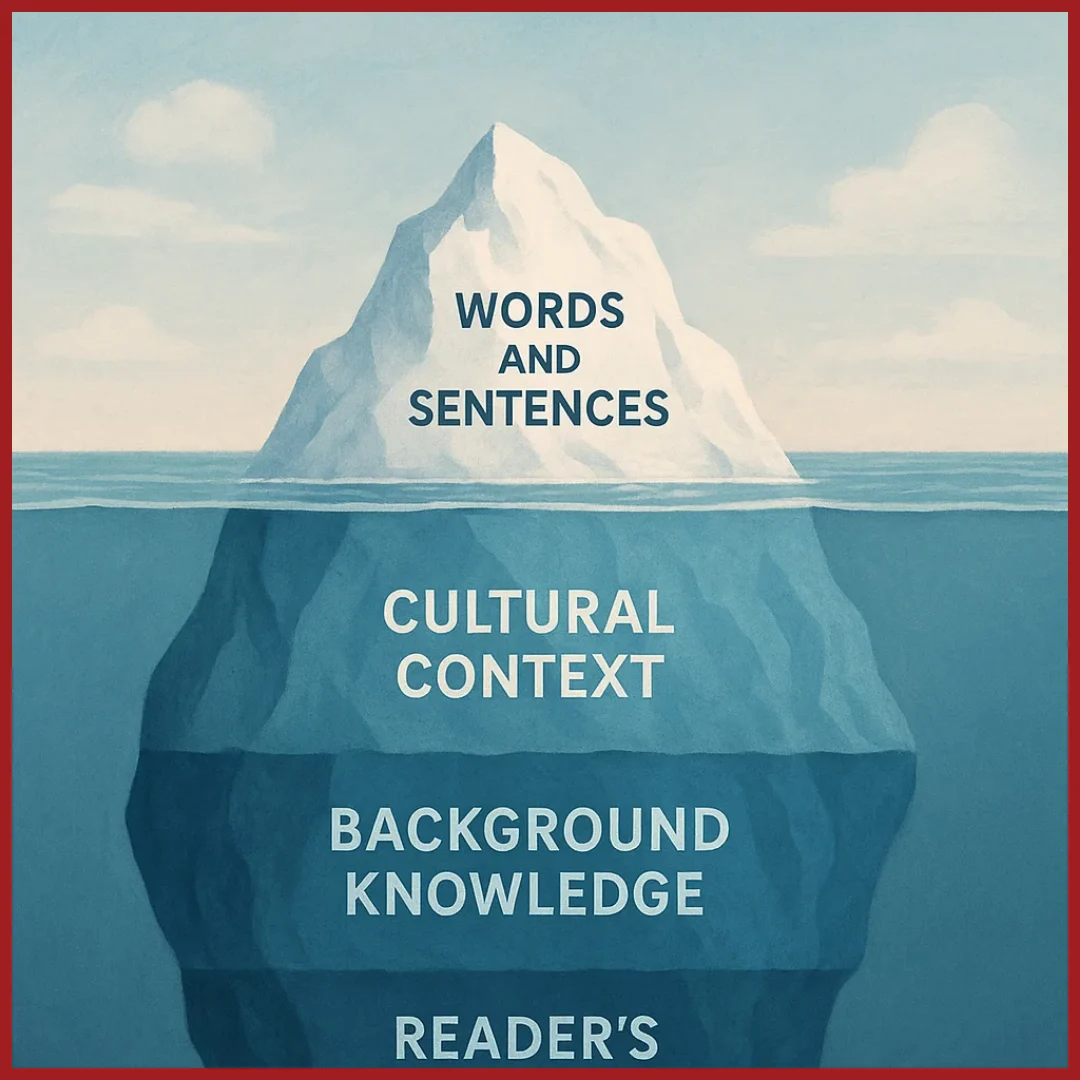

In the ever-evolving landscape of education, one question persists: how do we capture and sustain our students’

attention in a world filled with distractions? The traditional model of passive learning—where children quietly

absorb information—is not effective. Today’s learners crave interaction, relevance and engagement; they want to

be participants, not observers. In a world of reels and social media stories, delayed gratification seems to be an

artefact of the past and it won’t be a surprise if ‘attention’ will soon be the most valuable and rare resource on

Earth.

Why Active Engagement Matters

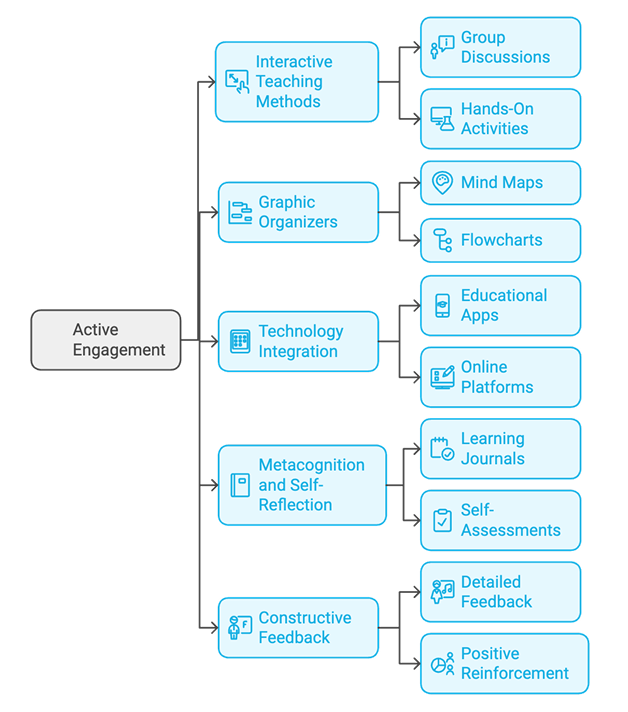

Active engagement isn’t just an educational buzzword; it is a necessity backed by research and neuroscience.

Understanding its importance can help us reshape our teaching methods to better serve our students. Research

consistently shows that active learning strategies improve student performance. A comprehensive study by

Freeman et al. (2014) underscores that when students actively participate in their learning, they not only

understand concepts better but also retain information longer.

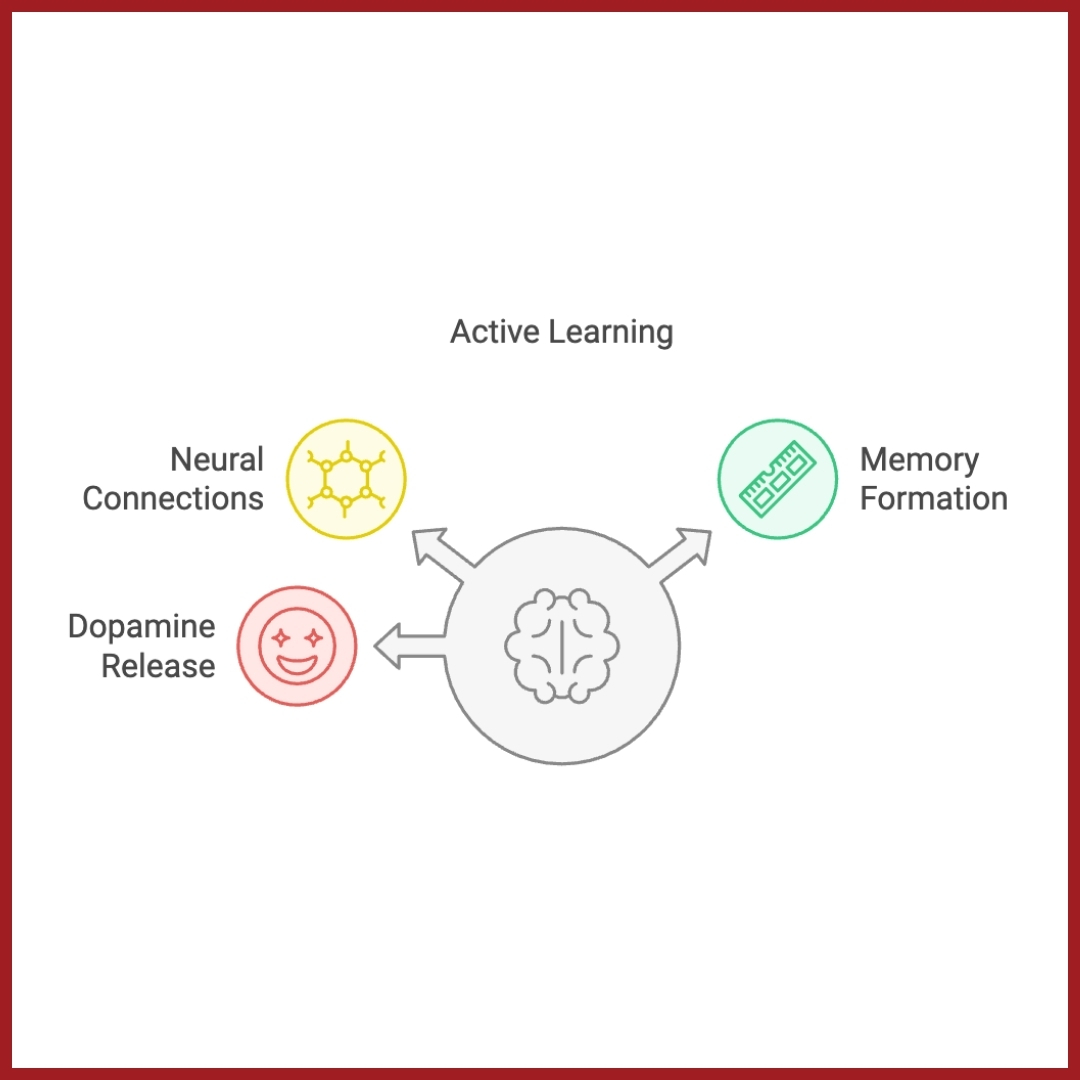

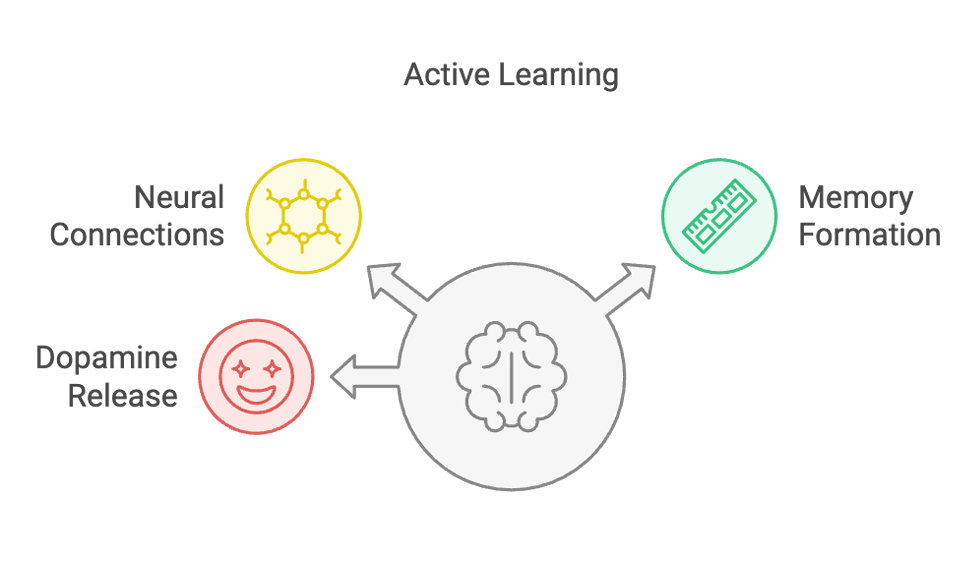

Modern neuroscience explains why active engagement is so effective. Active learning stimulates neural

connections in the prefrontal cortex, enhancing decision-making and problem-solving skills (National Reading

Panel, 2000). It also engages the hippocampus, crucial for forming long-term memories (Stahl & Fairbanks,

1986), and releases dopamine, increasing motivation and the pleasure associated with learning. These

neurological impacts facilitate deeper learning and retention

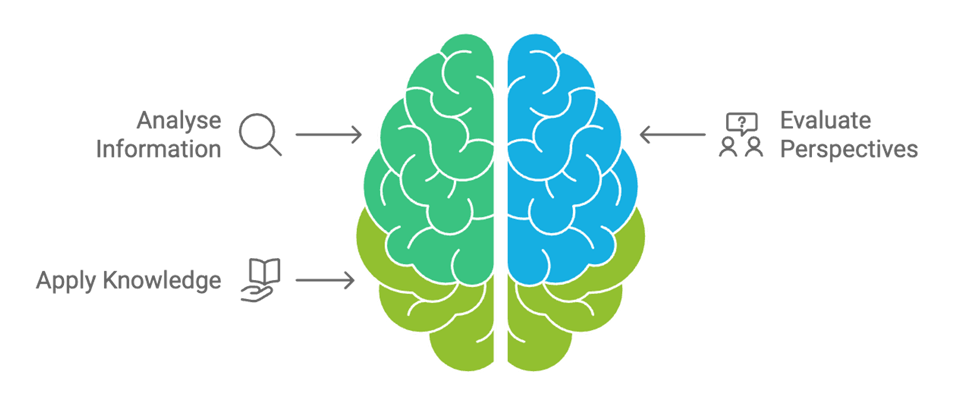

Why does this matter for day-to-day teaching? Because the skills most demanded by employers — critical thinking, collaboration and creativity — are the natural by-products of an actively engaged classroom. When students defend an argument or iterate a design, they rehearse exactly the habits that modern workplaces value. Active engagement is therefore not an add-on; it is the instructional core.

Children who are actively engaged in a topic have a better opportunity to:

This approach not only prepares students academically but also equips them with essential life skills.

Cultivating Curiosity: The Driving Force Behind Learning

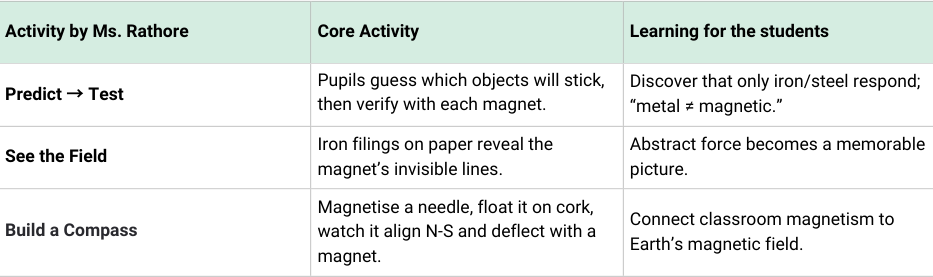

Curiosity is the proverbial spark that ignites the flame of learning. As educators, nurturing this innate desire to explore is one of our most important roles. Consider the story of Ms. Rathore, a fifth-grade teacher who transformed her classroom by embracing curiosity. To bring the chapter on magnetism alive, Ms. Rathore swapped chalk-talk for a single Mystery Box packed with: two magnets (bar and horseshoe), a handful of everyday objects, a pouch of iron filings, a needle, cork, and bowl of water.

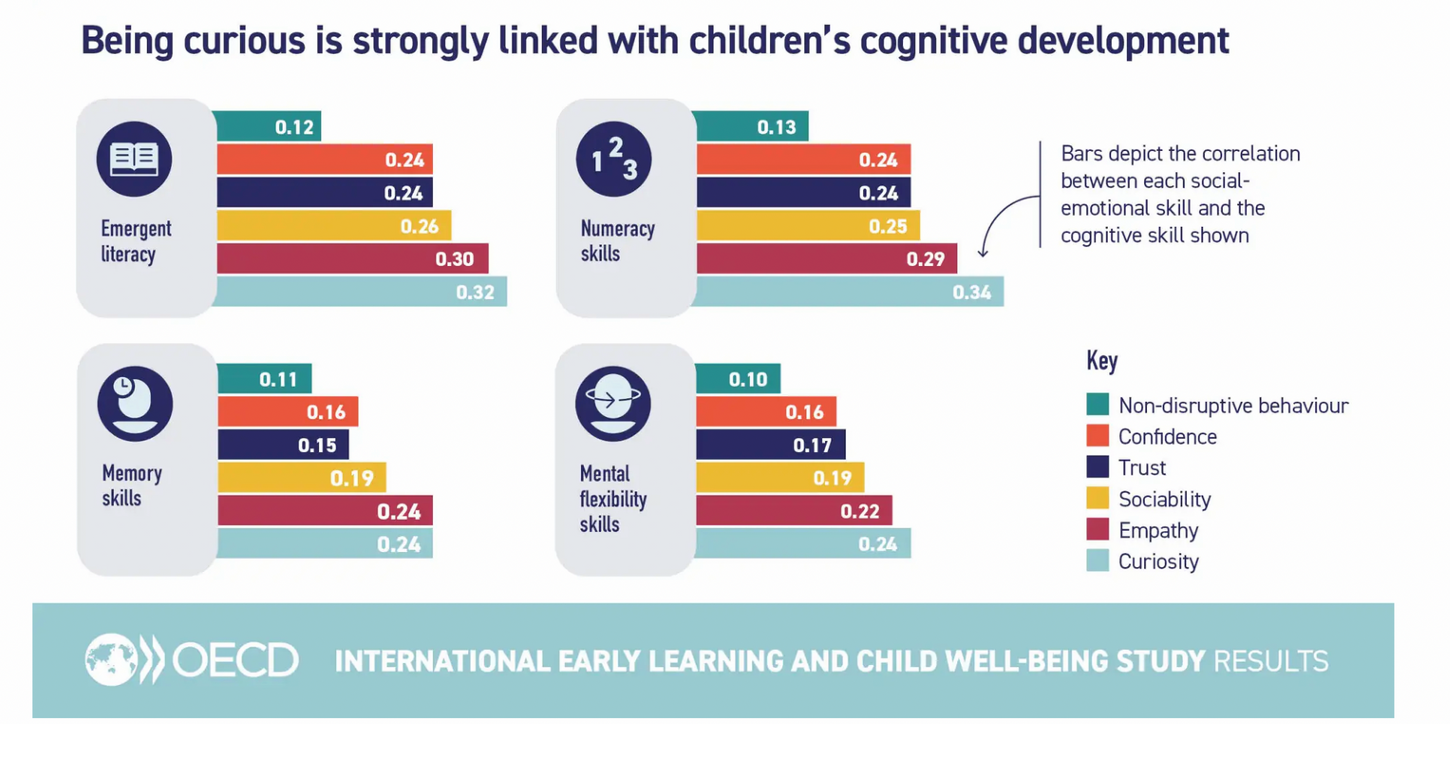

With one low-cost box and three quick tasks, learners were required to predict, observe, build, and explain, turning a routine chapter into lasting understanding. What do you think Ms. Rathore was trying to leverage in her classroom? Definitely, the students’ curiosity. This is not whimsy; it is data. The OECD’s Early Learning and Child Well-being Study tracked five-year-olds in ten countries and found that those who frequently asked ‘why?’ scored significantly higher in literacy, numeracy and cognitive flexibility four years later.³ Curiosity, it turns out, teaches children how to learn long after they forget what chlorophyll is.

Curiosity also reshapes classroom culture. When questions, not answers, earn applause, even shy students risk raising a hand. The atmosphere tilts from one of evaluation to one of exploration — less ‘prove you know’ and more ‘let’s find out together.’ Teachers report a measurable drop in low-level disruption; you cannot text under the desk when you are itching to know why bubbles rise faster in hot water than in cold.

Building a curiosity loop. Once a question sparks inquiry, children collect evidence, share provisional ideas and pose new questions. This cyclical process keeps motivation high and deepens understanding with every turn. The teacher’s role shifts to being a curator of resources and a coach of thinking moves

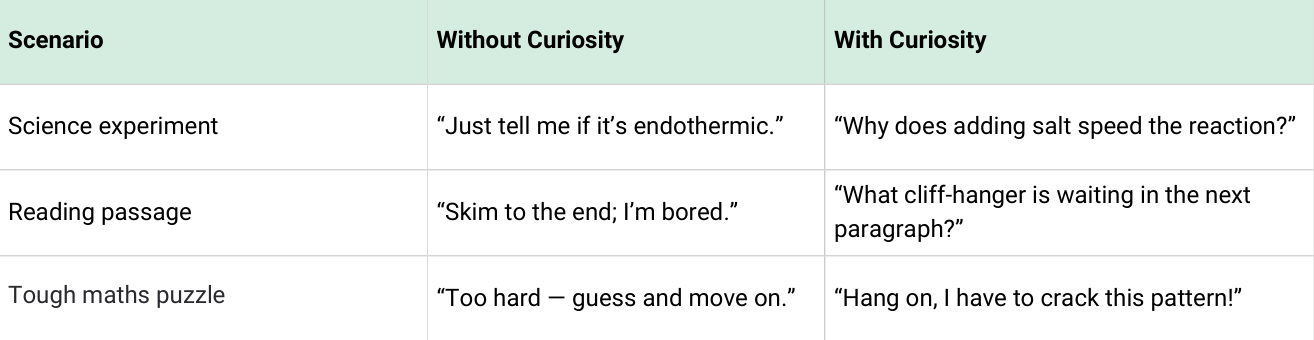

Curiosity Increases Effort

Overcoming Barriers to Curiosity

Curiosity can be snuffed out by syllabus overload, fear of a high-stakes exam or a one-size-fits-all instruction.

- Differentiate up and down. Offer ‘challenge corners’ with extension puzzles, plus scaffolded entry points for hesitant learners — so everyone meets productive difficulty

- Reward the question, not just the answer. House points or digital badges for thoughtful queries signal that inquiry is currency.

- Blend explicit teaching with exploration. Direct instruction provides the map; exploratory tasks let pupils test-drive the terrain

- Blend explicit teaching with exploration. Plan for wait-time. Pausing a full seven seconds after asking a question raises both the number and depth of student responses.

Teachers worry that curiosity-based detours ‘eat time’, yet studies show that students who construct knowledge through inquiry often reach standard benchmarks faster and retain them longer. The key is designing tasks with a clear purpose and anchor points, so curiosity fuels, rather than fragments, the journey.

The Role of Assessments in Active Engagement

Summative assessments, too, can honour active learning: podcasts explain historical controversies, prototypes solve local water issues, debates test civic reasoning. When what we value (curiosity, problem-solving, collaboration) also gets measured, classroom culture locks into alignment.

Balancing breadth and depth. Mapping formative checkpoints to curricular goals ensures coverage while leaving space for deeper dives. Transparent rubrics help pupils track progress and self-correct without waiting for teacher intervention

Conclusion

You don’t need to redesign the whole timetable. Try one small switch this week: swap a lecture for a quick debate, replace a worksheet with a mystery box, or turn a right-answer quiz into a short reflection journal. These simple moves invite questions, hands-on exploration and honest thinking—three habits that anchor deep understanding

Stand back and watch. Curiosity will do the heavy lifting, stretching the brain’s ‘learning muscles’ and showing children that challenge is something to lean into, not dodge. When that happens, you’ll know you’ve built a classroom where every student feels the thrill of finding out

Are these principles already part of your teaching toolkit? We’d love to hear your story!

References used in the article:

- Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012). Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. International Society for Technology in Education

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415.

- Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D., & Ranganath, C. (2014). States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron, 84(2), 486–496.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational Researcher, 38(5), 365–379.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training. (2020). National Curriculum Framework for School Education.

- National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- OECD. (2021). International Early Learning and Child Well-being Study (IELS). OECD Publishing.

- Stahl, S. A., & Fairbanks, M. M. (1986). The effects of vocabulary instruction: A model-based meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 56(1), 72–110.

Enjoyed the read? Spread the word

Interested in being featured in our newsletter?

Feature Articles

Join Our Newsletter

Your monthly dose of education insights and innovations delivered to your inbox!

powered by Advanced iFrame