Edition 02 | February 2025

Feature Article

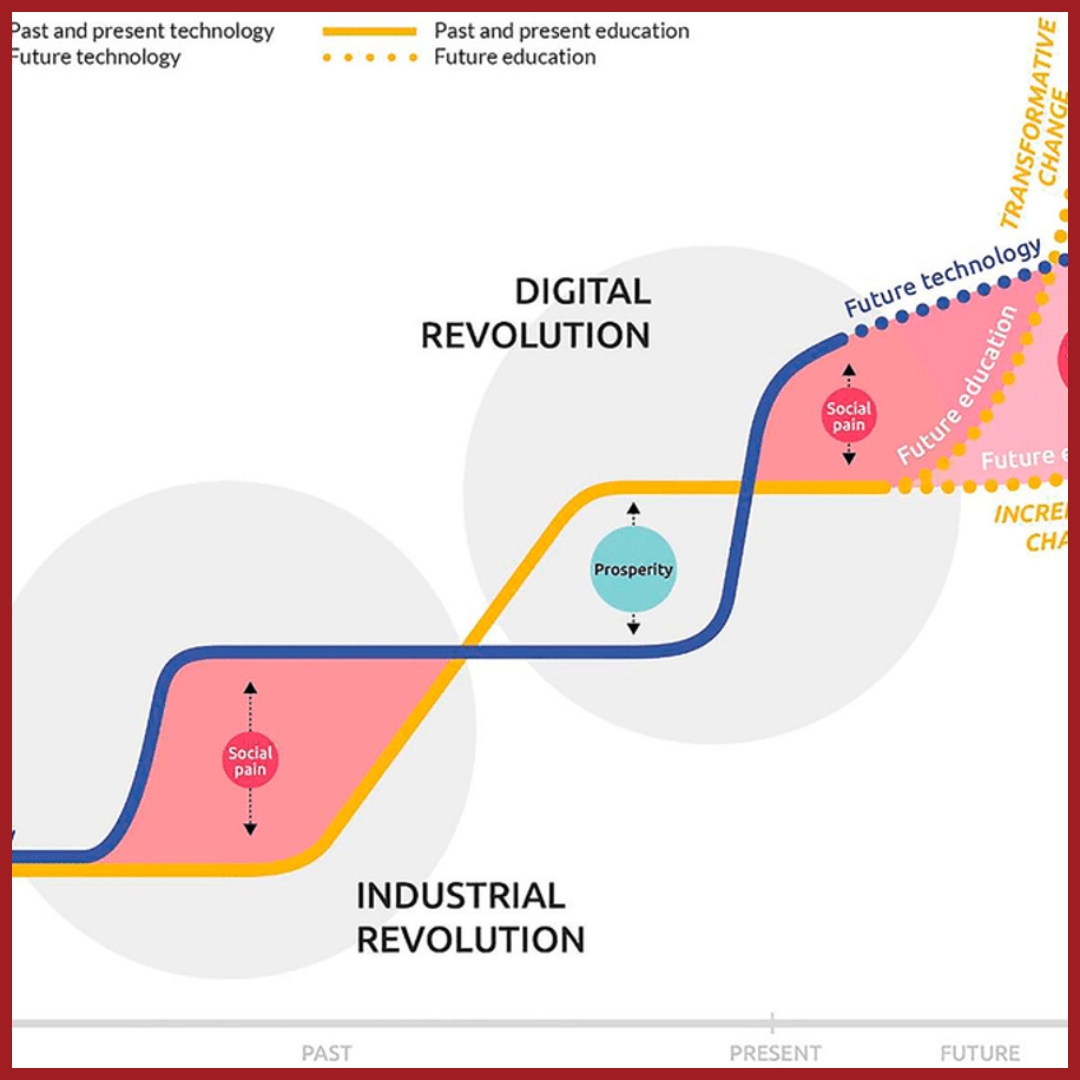

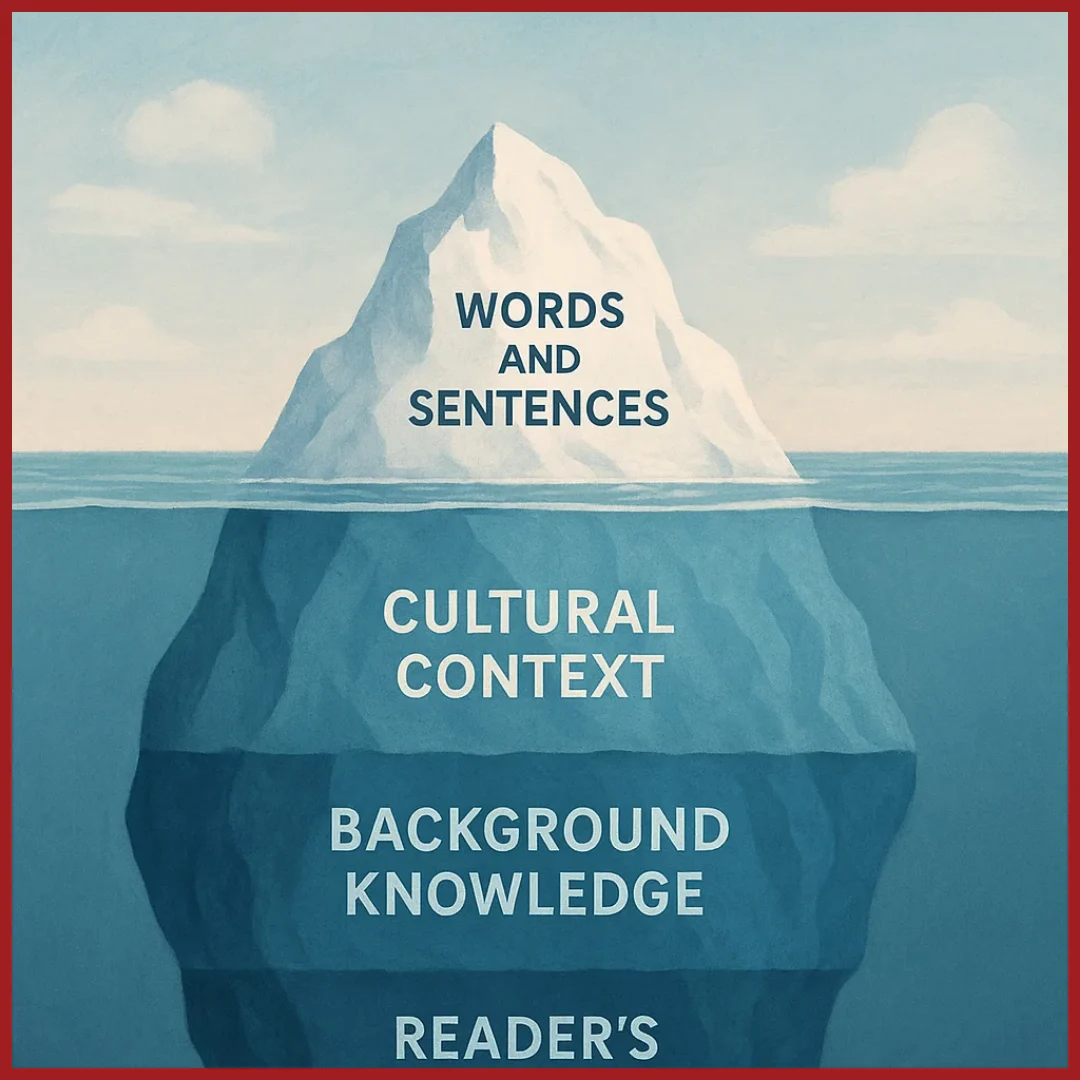

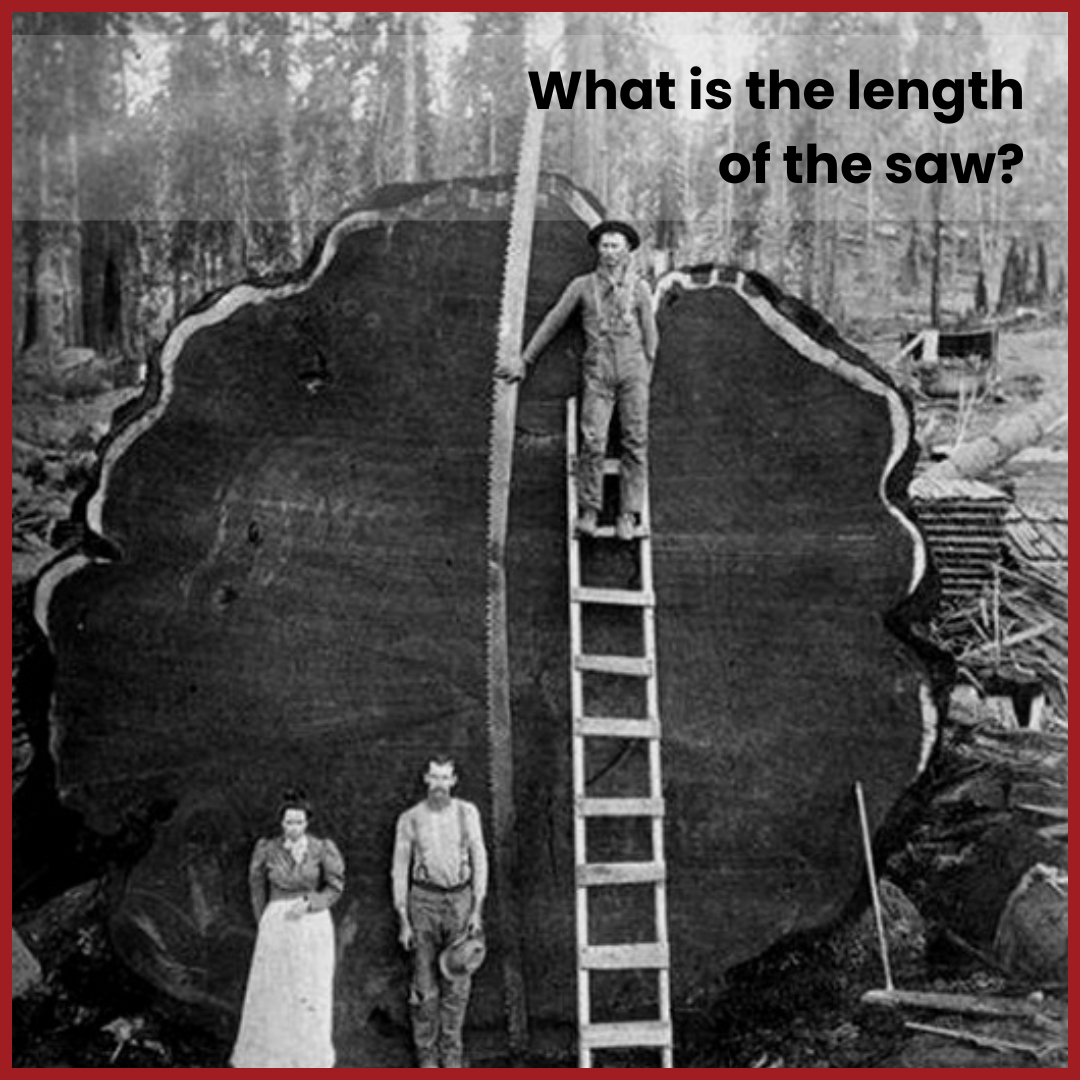

Education has always adapted to the needs of the societies it serves. In ancient Greece, Socrates championed a teaching style that prioritised dialogue, encouraging students to question, debate, and think critically. Similarly, the Chandogya Upanishad highlights the story of guru Uddalaka guiding his son Shvetaketu not with answers but with probing questions to foster independent thought. The Katha Upanishad presents another example, where Nachiketa’s dialogue with Yama exemplifies inquiry and critical thinking as tools to uncover wisdom. These ancient methods recognised the importance of student agency in learning. However, the Industrial Revolution brought a dramatic shift. Education became rigid, uniform, and teacher-centred, mirroring the efficiency of factory systems. Schools prioritised discipline and rote memorisation to produce workers capable of following instructions, sidelining creativity and reducing students to passive recipients of knowledge. While this model served its purpose, it began to falter in the late 20th century as societies transitioned into knowledge economies, where adaptability, innovation, and critical thinking became indispensable.

The pace of technological advancements in the 21st century has only magnified these inadequacies in traditional education systems. As the famous science fiction writer Isaac Asimov observed, “The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.” This gap between knowledge acquisition and practical wisdom has had real consequences. Reports like A Nation at Risk (1983) in the United States highlighted the failure of schools to equip students with the critical thinking and problem-solving skills necessary for modern careers and civic engagement. Similarly, in India, the persistent dominance of rote learning and exam-oriented systems received widespread criticism for stifling creativity and deeper understanding.

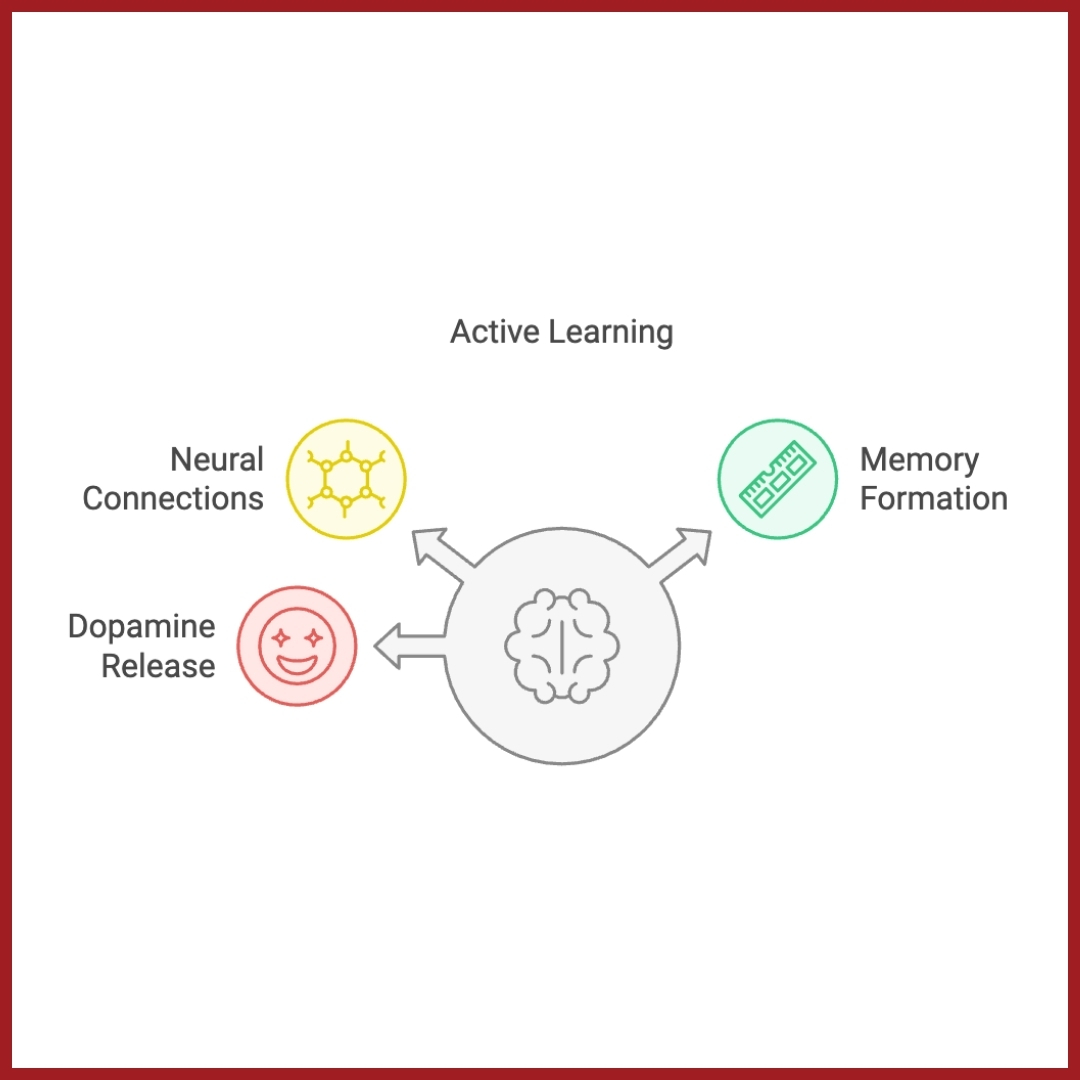

Further evidence of the limitations of traditional teaching comes from experts in science and education. For example, Harvard physicist Eric Mazur demonstrated through his Peer Instruction method that student collaboration, discussion, and problem-solving foster a deeper understanding of concepts than traditional lectures, which often lead to surface-level knowledge. Similarly, MIT physicist Walter Lewin inspired students worldwide through his dynamic teaching methods, using engaging demonstrations to make complex physics concepts relatable and accessible. These examples highlight a common theme: when students are actively engaged, learning becomes meaningful and long-lasting. Recognising this, innovative education systems globally have begun to adopt models prioritising relevance, creativity, and critical thinking. Finland, for instance, introduced thematic, student-centred curricula, while Singapore adopted project-based learning approaches, both designed to foster lifelong learning and real-world problem-solving.

What is Student-Centred Learning?

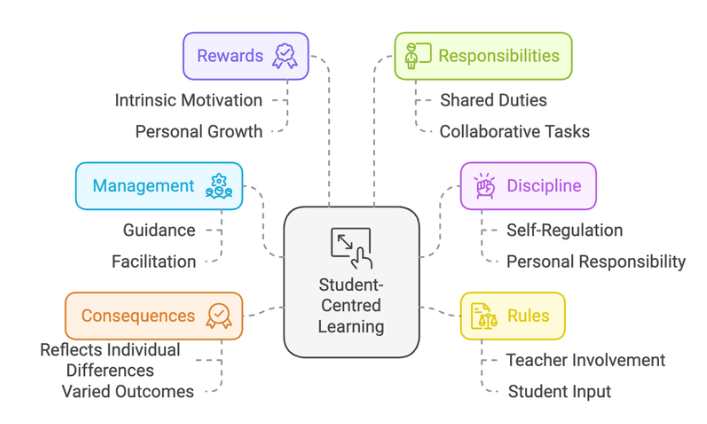

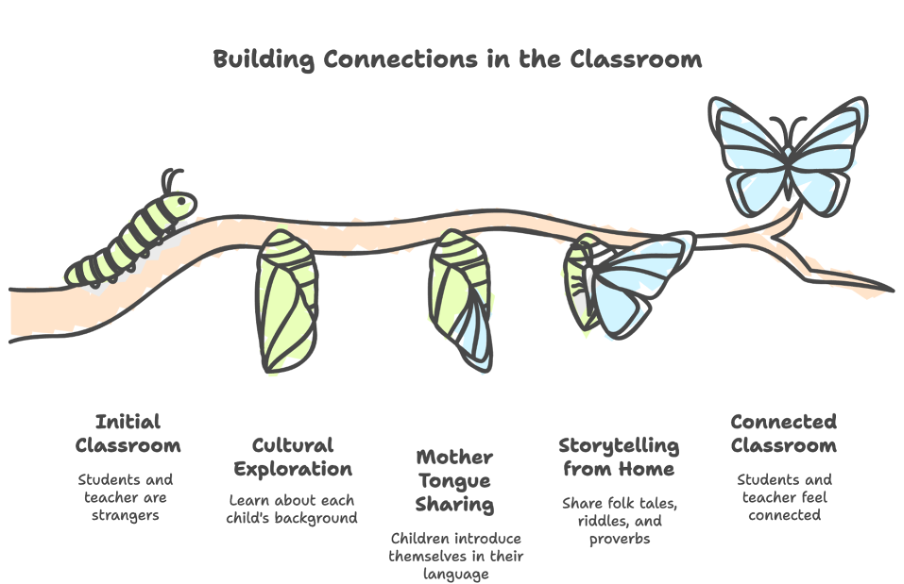

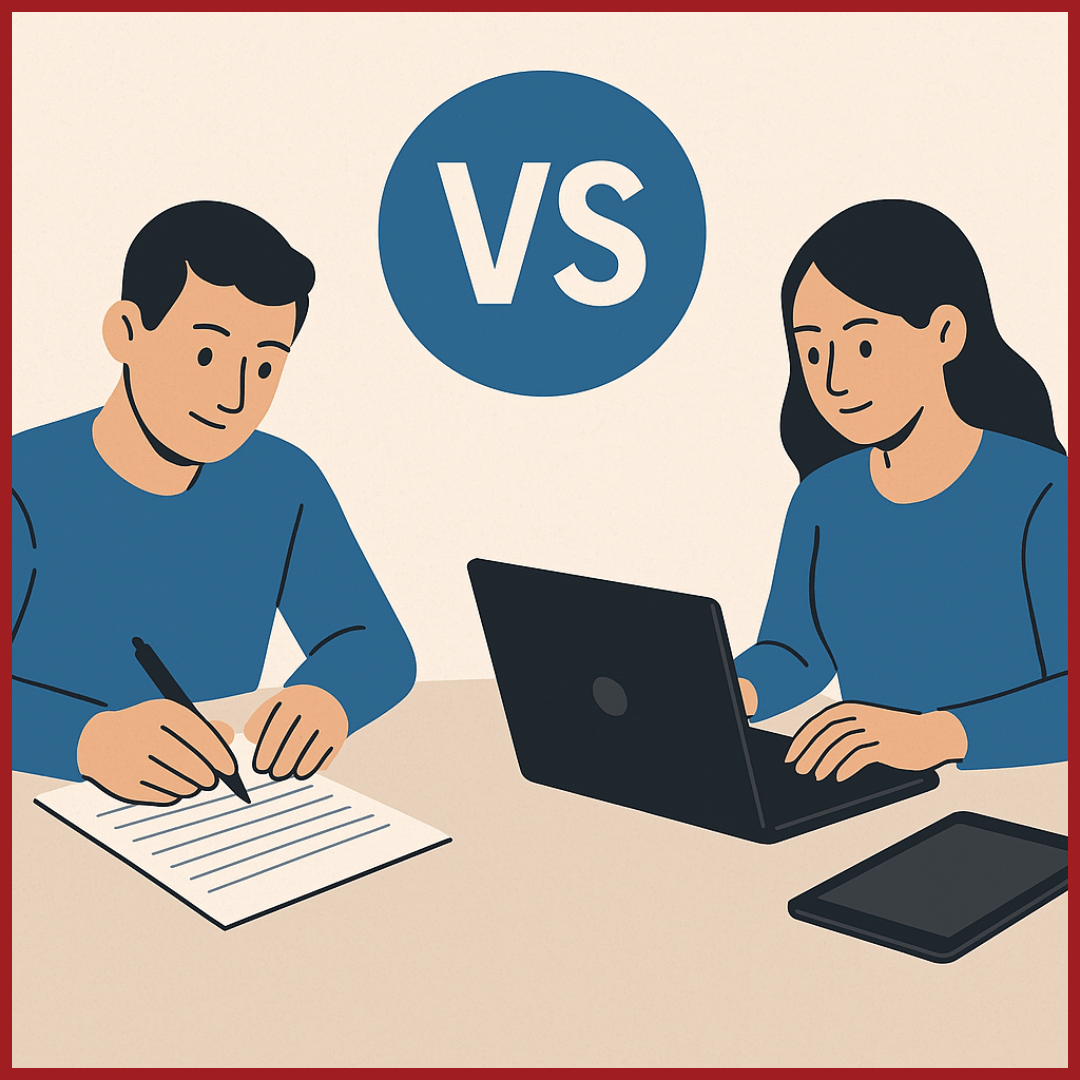

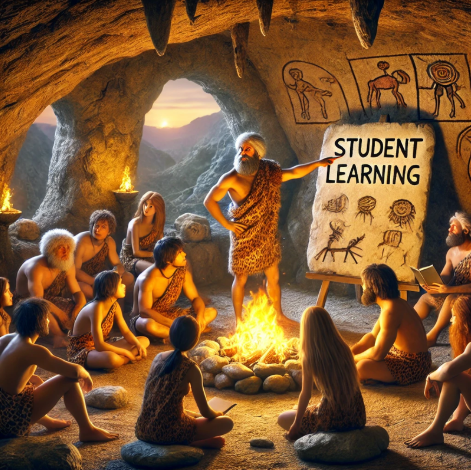

Student-centred learning focuses on the needs, interests, and abilities of individual students, placing them at the heart of the learning process. It encourages active participation, where students explore real-world problems, collaborate with peers, and make meaningful connections to their learning. In such environments, teachers act as facilitators, guiding students to take ownership of their educational journey. A typical student-centred classroom is dynamic, engaging, and flexible, catering to the diverse ways in which students learn.

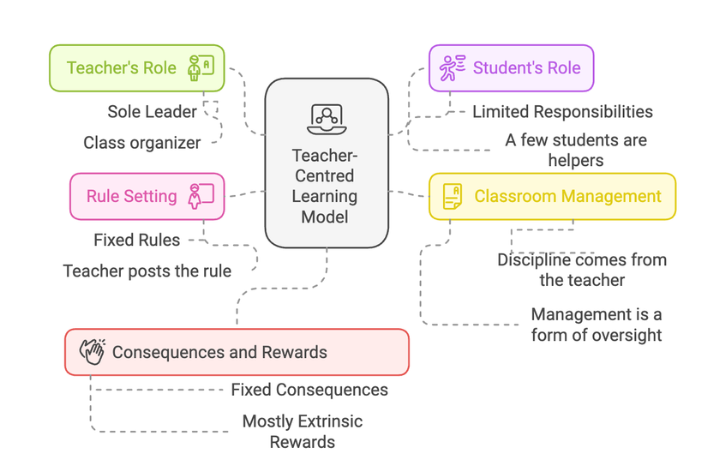

Conversely, teacher-centred learning revolves around content delivery, with teachers directing the flow of lessons and students passively absorbing information. While this model ensures structure and consistency, it often fails to engage learners meaningfully. Striking a balance between these two approaches allows teachers to maintain rigour while encouraging student agency, creativity, and curiosity.

Adapted from Freedom to Learn, 3rd Edition (p. 240) by C. Rogers and H. J. Frieberg, 1994. Columbus: Merrill Publishing. Copyright 1994 by Prentice-Hall, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Why Student-Centred Learning Matters?

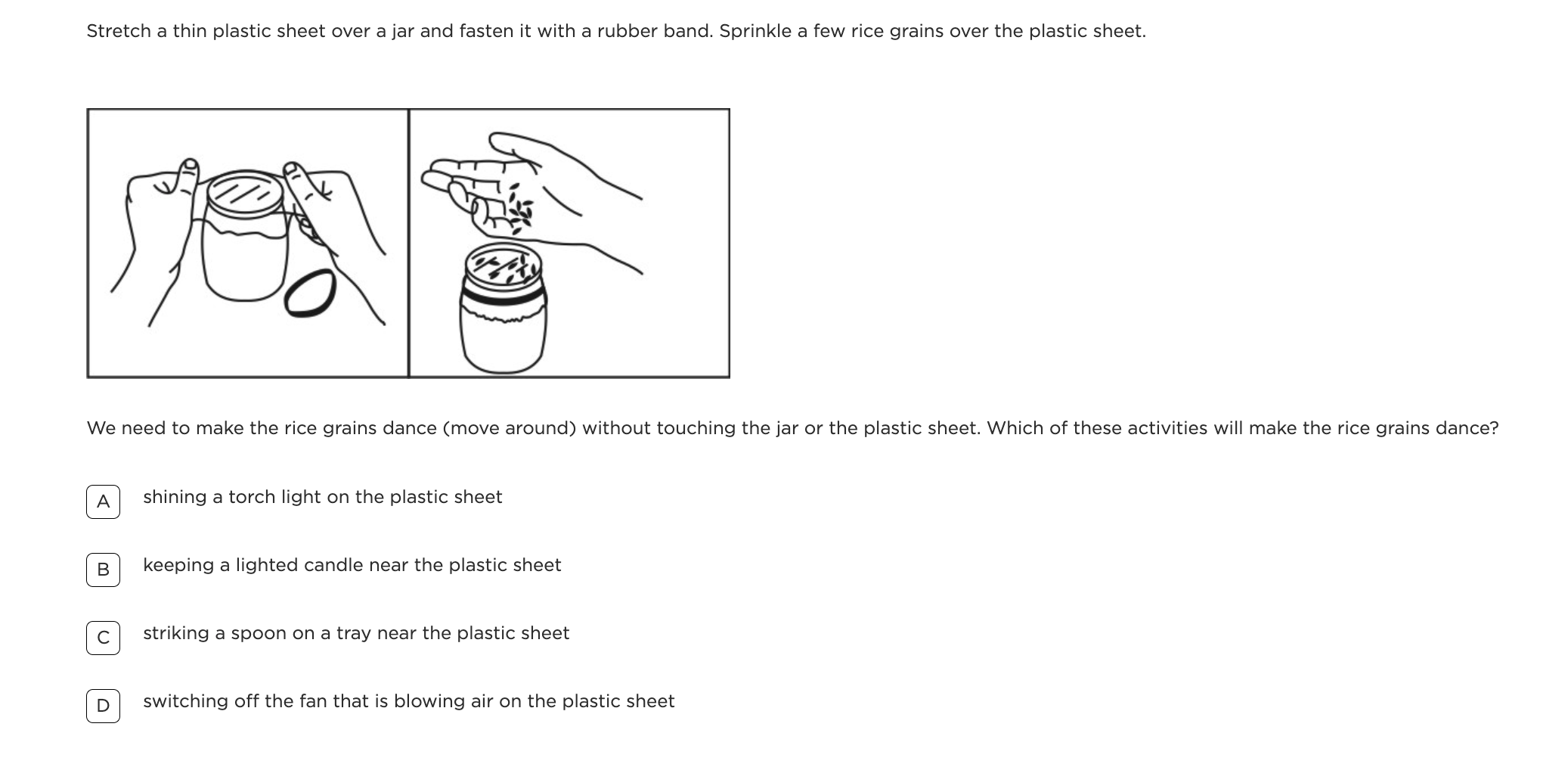

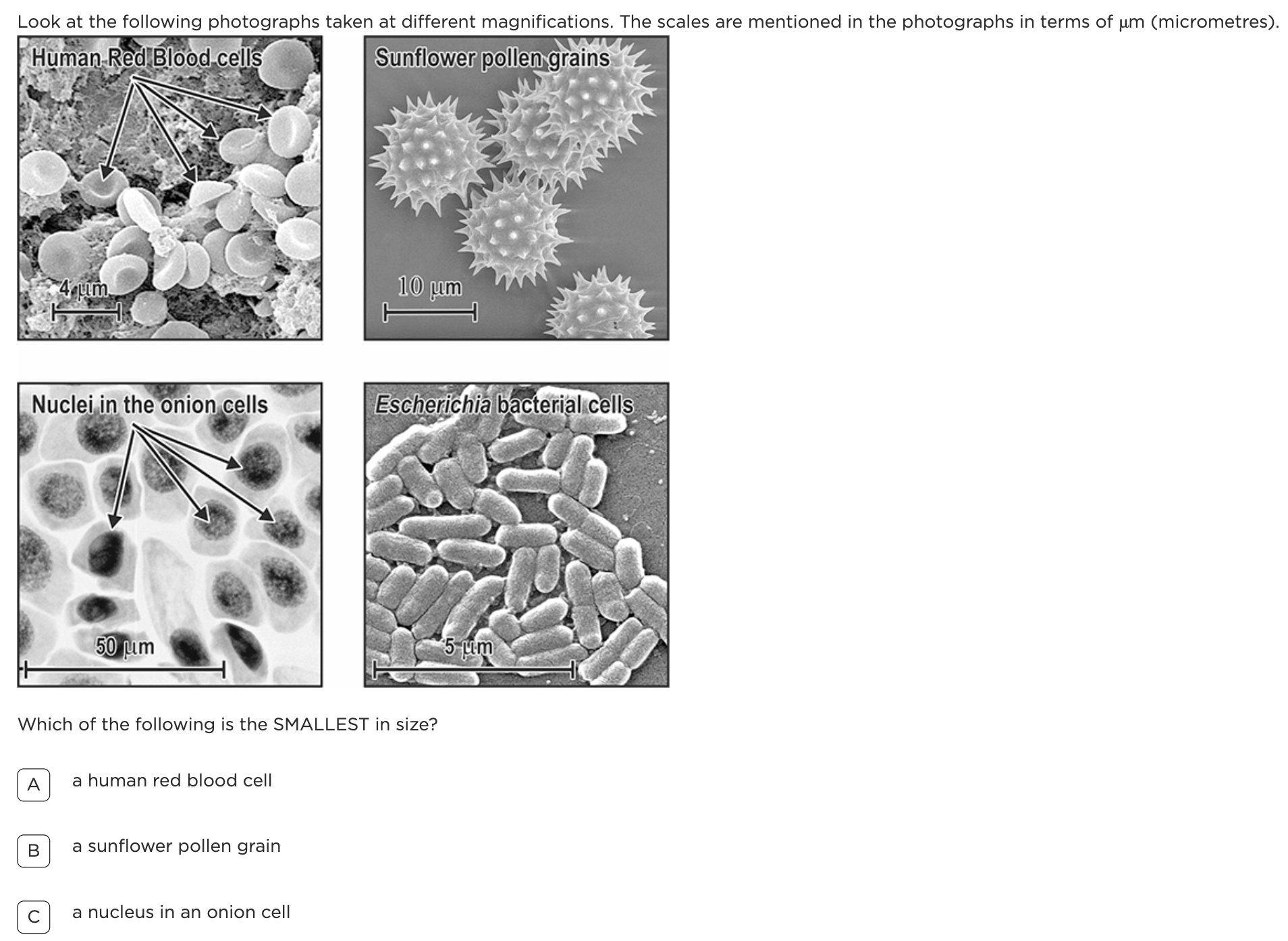

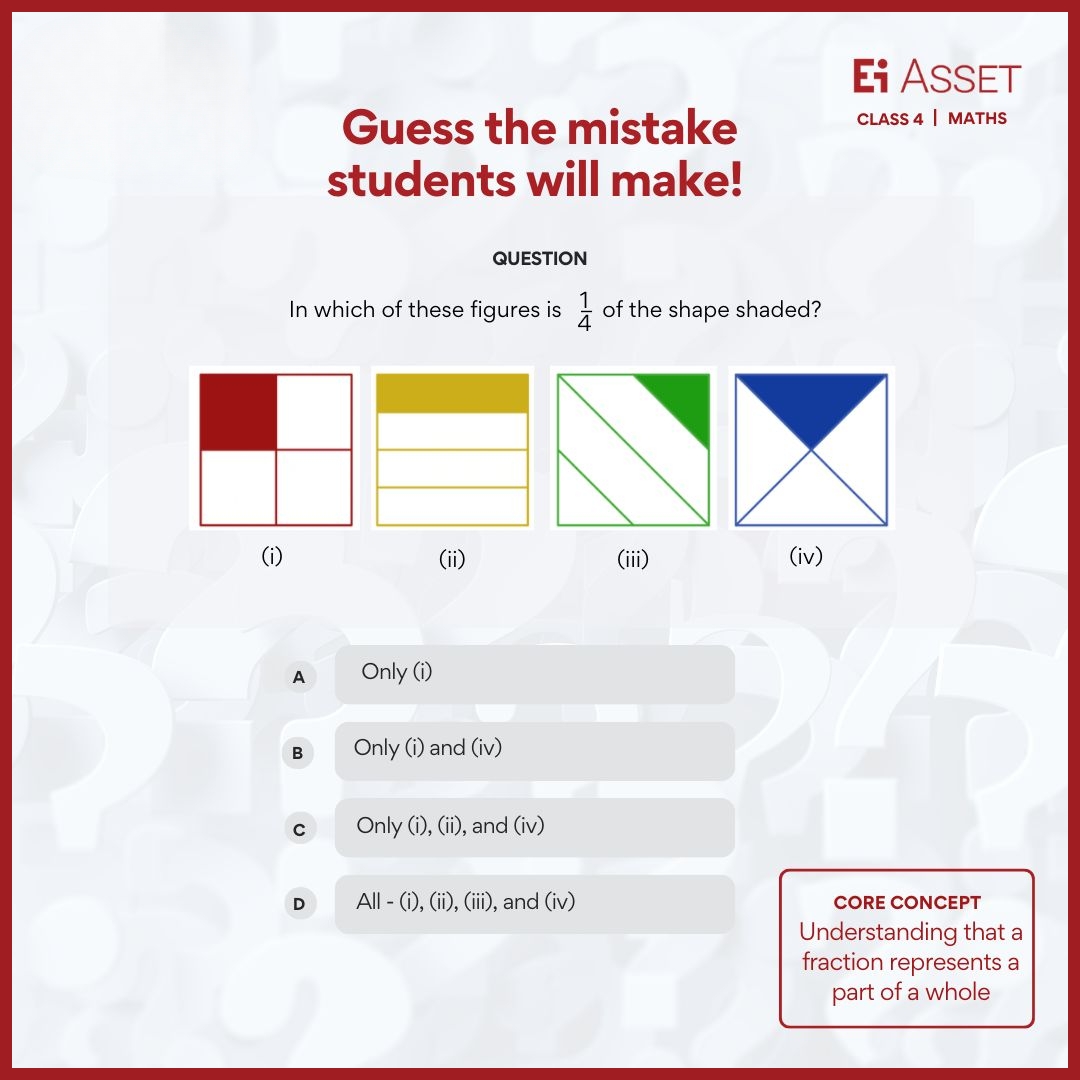

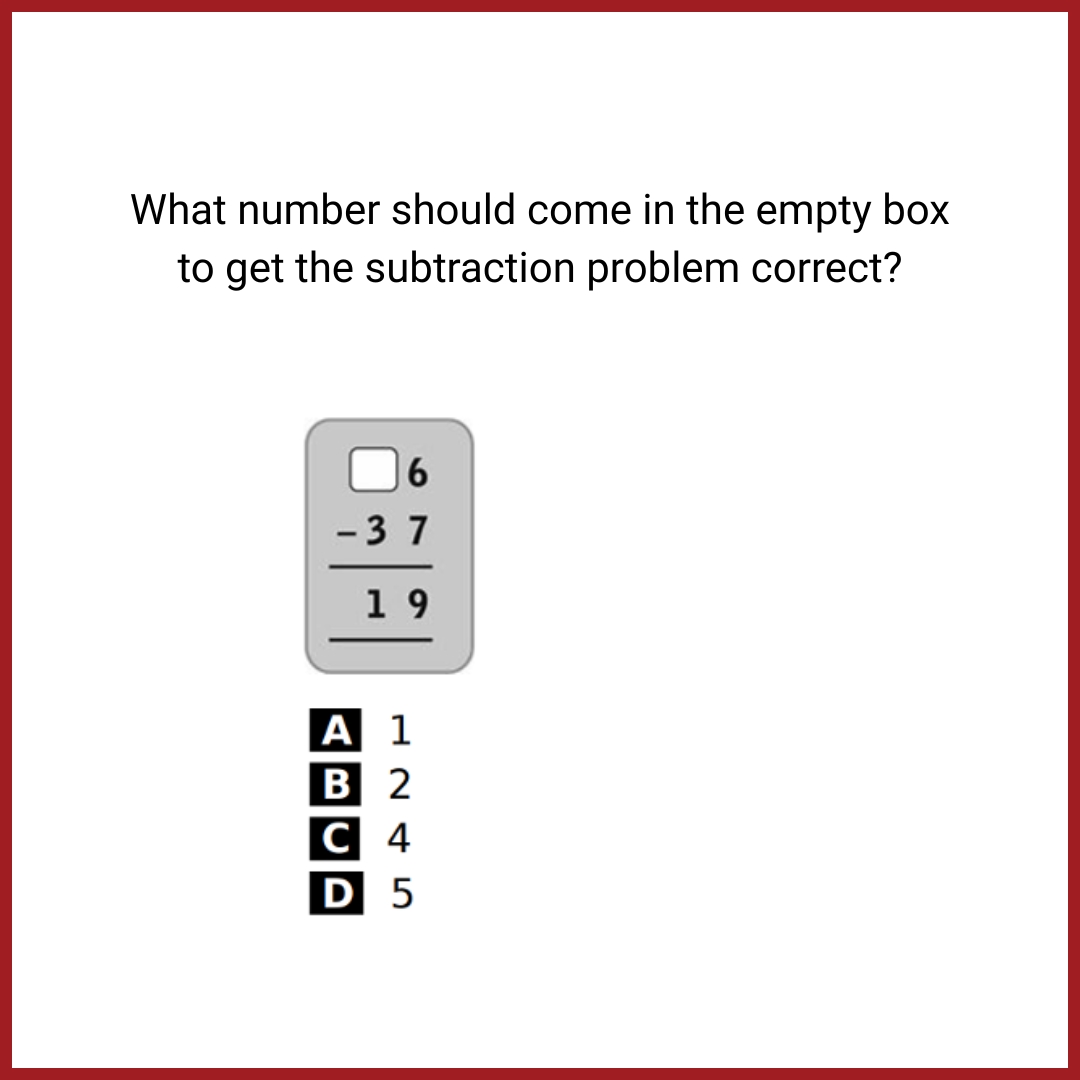

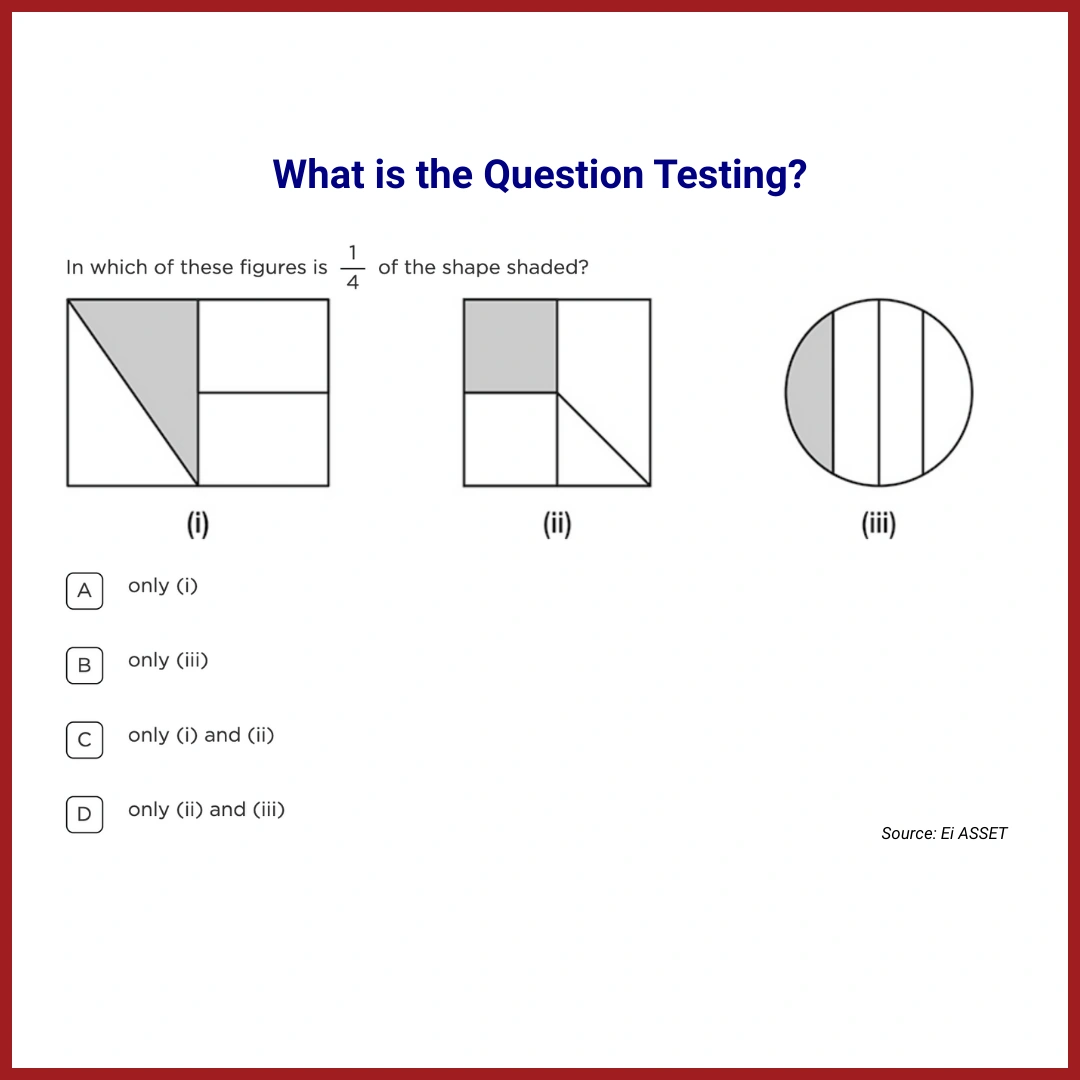

The shift to student-centred learning is not just a trend—it addresses critical gaps in traditional education. Research consistently shows that students learn more effectively when they are actively involved. Consider a student in a conventional classroom memorising mathematical equations to pass an exam. Now, imagine the same student designing a sustainable city, applying those equations to calculate energy efficiency. This project not only teaches mathematical concepts but also fosters critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving.

Student-centred learning recognises that every child is unique. Some thrive in collaborative group projects, while others excel in self-directed research. This flexibility ensures that all learners can engage with content in ways that align with their strengths while also pushing them to develop new skills. Moreover, this approach mirrors real-world scenarios, where individuals must collaborate, adapt, and think critically.

The Teacher’s Role: Evolving, Not Disappearing

Despite the emphasis on student autonomy, teachers remain central to the success of student-centred learning. In fact, their role becomes even more critical. They are no longer merely transmitters of knowledge but designers of meaningful learning experiences. Research supports this shift. A systematic review by HRMARS highlights that project-based learning (PjBL) significantly enhances children’s critical thinking and problem-solving skills by engaging them in real-world, collaborative, and analytical tasks. Teachers must establish strong foundational knowledge, ensuring students have the tools they need to explore, innovate, and solve complex problems.

Additionally, teachers maintain balance in the classroom. A fully student-driven environment risks descending into chaos without clear boundaries and expectations. Teachers provide the structure necessary to keep students focused and aligned with learning objectives. Beyond academics, teachers create safe, nurturing spaces where students feel valued and respected. This emotional foundation is essential for meaningful learning, building the confidence students need to take risks and tackle challenges.

The Post-COVID Shift: Why Teachers Matter More Than Ever?

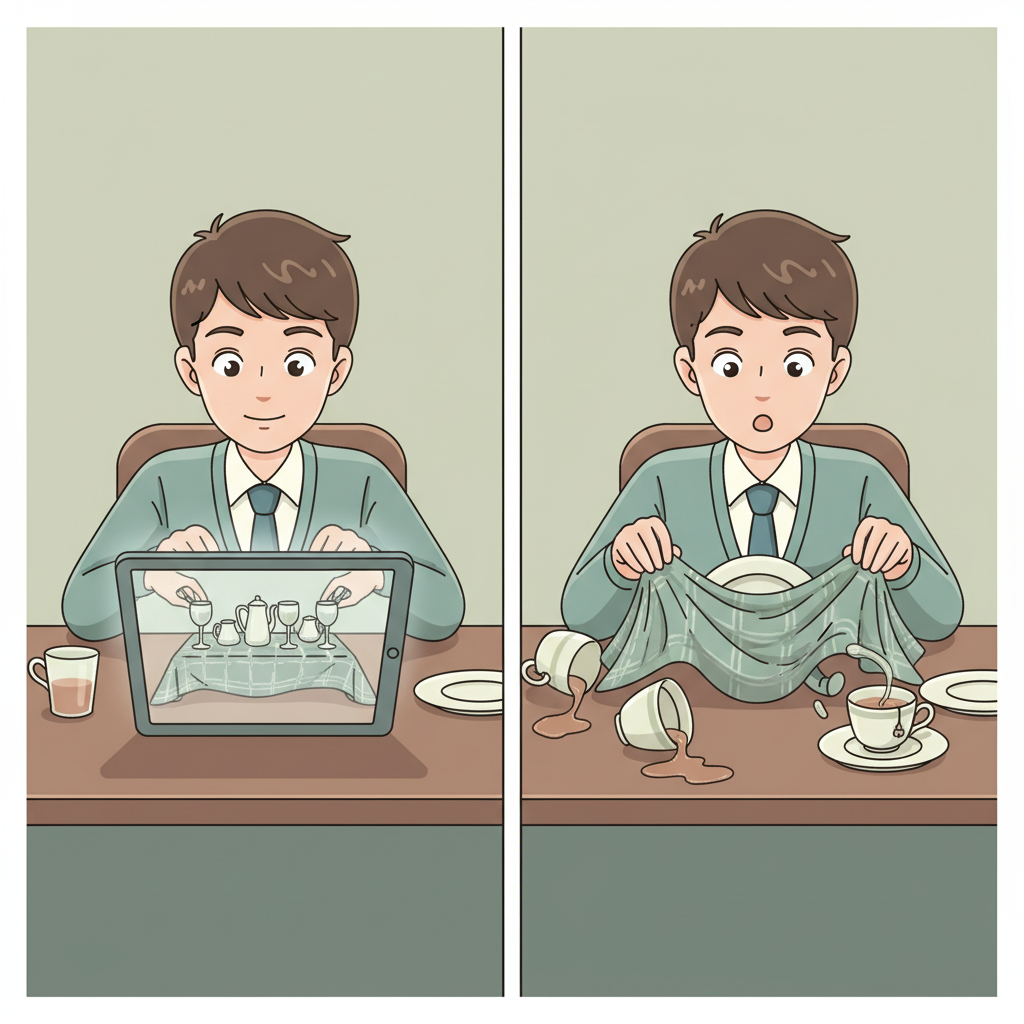

The COVID-19 pandemic transformed the educational landscape. Remote learning disrupted traditional models, accelerating the adoption of digital tools and hybrid classrooms. This shift has ruptured the envelope of space, time, and student attention. Students now require greater autonomy and self-regulation to navigate these changes, but they also need robust teacher support to bridge gaps in understanding and engagement.

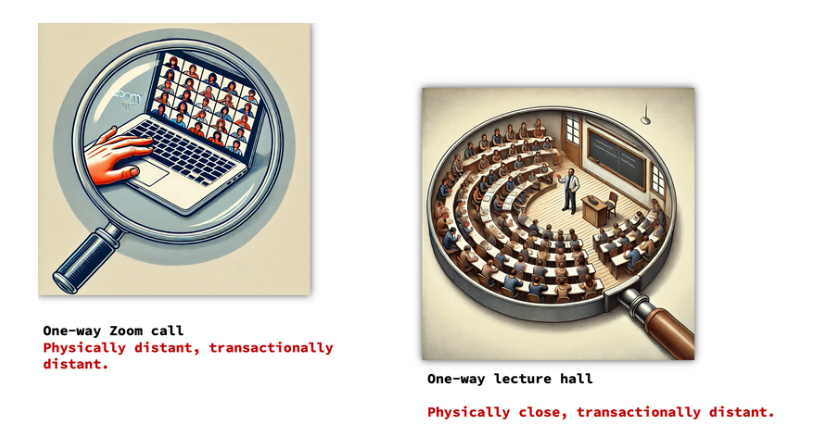

Moore’s Theory of Transactional Distance offers valuable insights here, describing how the physical, psychological, or communication gap between students and teachers can hinder learning outcomes.

The theory suggests that the greater this distance, the more guidance and structure are required to ensure learning. In a post-COVID world, where transactional distance has increased due to online and hybrid learning models, the role of teachers in bridging this gap is more important than ever. They must adapt their strategies to manage this complexity, blending digital tools with traditional methods to create cohesive learning experiences.

Challenges and Complexities of Modern Classrooms

While student-centred learning is promising, it is not without challenges. Personalised instruction, differentiated assessments, and collaborative projects demand significant resources, including smaller class sizes, well-trained teachers, and access to technology. Many schools, particularly in underfunded systems, struggle to meet these demands.

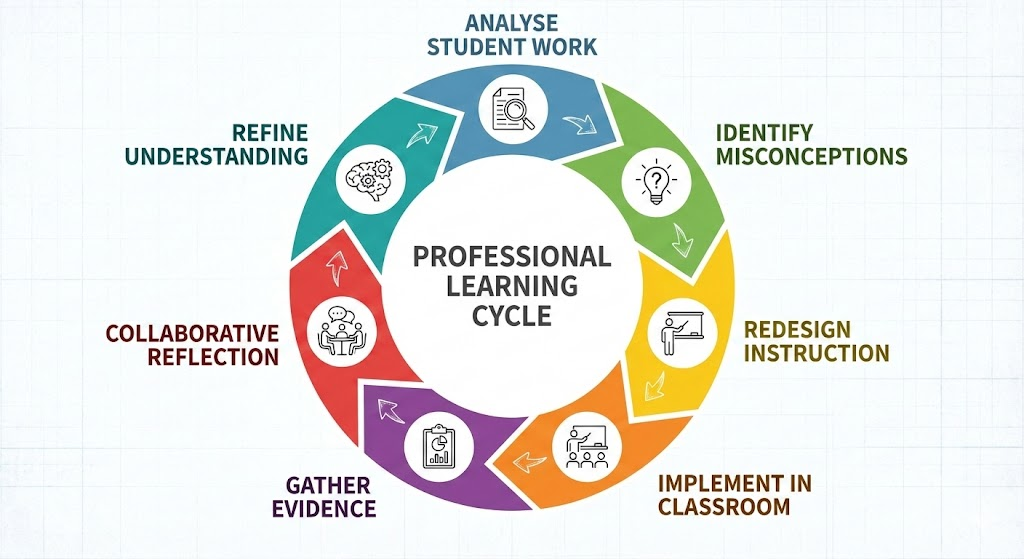

There is also the issue of inequity. Students with strong self-discipline and supportive home environments often thrive in student-centred settings, but those lacking these advantages may struggle without adequate teacher intervention. This underscores the need for professional development to equip teachers with the skills to manage diverse classrooms effectively.

Moreover, transitioning to a student-centred approach requires a mindset shift for both teachers and students. Educators must move away from traditional methods, while students must develop self-regulation and accountability—skills that not all learners possess initially. Without careful implementation, student-centred learning risks widening existing gaps rather than bridging them.

What Success Looks Like

Effective student-centred learning strikes a balance between innovation and structure. Blended learning models, illustrate how technology can complement teacher-led instruction, improving outcomes in literacy and numeracy. Project-based learning, when done well, exemplifies the best of student-centred education, connecting academic content to real-world applications. However, these projects must be carefully designed, with clear rubrics, checkpoints, and feedback mechanisms to ensure rigour.

Differentiated instruction is another cornerstone of success. In recognition of the fact that students have varying learning needs, this approach tailors content and methods to meet individual requirements, ensuring that all learners can thrive. Collaborative goal-setting further enhances this process, involving students in decisions about their learning and fostering a sense of ownership.

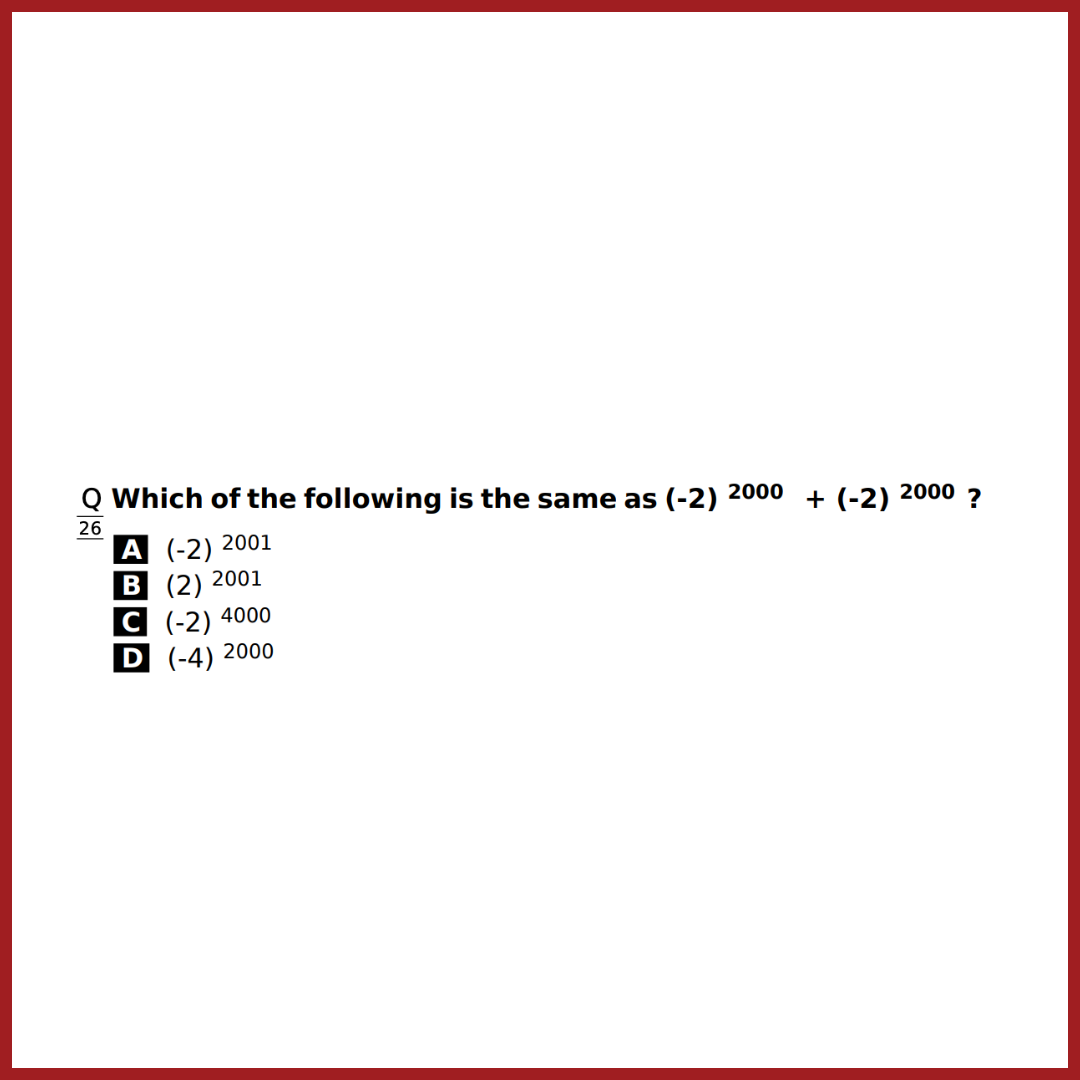

Assessment, too, must evolve. Traditional high-stakes tests often fail to capture the nuances of student learning. Robust formative assessments provide ongoing feedback that helps both students and teachers adapt their strategies.

Looking Ahead

The promise of student-centred learning lies not in replacing traditional methods but in complementing them. It’s about recognising that education is not a one-size-fits-all endeavour. By valuing both student agency and teacher expertise, we can create classrooms that are dynamic, engaging, and inclusive.

Teachers are not becoming redundant; they are becoming more essential than ever. They are the architects of meaningful learning experiences, mentors guiding students through challenges, and coaches fostering curiosity and resilience. As India’s education system evolves under the NEP 2020, the role of teachers in shaping this transformation cannot be overstated.

Education is a partnership—a collaboration between students, teachers, and the systems that support them. By embracing this partnership and investing in its success, we can ensure that student-centred learning is not just a buzzword but a meaningful step towards a brighter, more equitable future. As Jean Piaget eloquently put it-

“That which we allow [a child] to discover by himself will remain with him visibly for the rest of his life.”

Bibliography

Enjoyed the read? Spread the word

Interested in being featured in our newsletter?

Feature Articles

Join Our Newsletter

Your monthly dose of education insights and innovations delivered to your inbox!

powered by Advanced iFrame